The 18th century was an age of wars and social changes. In Europe in particular it was also the time that marked the birth of the Enlightenment – or “Age of Reason” – which inspired the drama of the French Revolution. To that bloody upheaval there followed a revolution of a different kind and one that saw the beauty and terror of science sweeping through Britain and Europe, producing a new vision of the world, of nature and religion.

The whole Era was one of revelation and vision for man.

London was then a European Capital city which shockingly and generously also provided entertainment of a sophisticated and extraordinary sexual nature. In his book entitled “The Secret History Of Georgian London” the historian Dan Cruickshank writes: “Although Georgian London evokes images of elegant buildings and fine art, it was, in fact, the Sodom of the modern age…Teeming with prostitutes – from lowly street walkers offering a ‘ threepenny upright’ to high-class courtesans retained by dukes – Georgian London was a city built on the sex trade“.

Georgian London hosted many whorehouses, “Bagnios”, flagellation brothels and homosexual clubs called “Molly houses”. The latter were dwellings were young men, or “mollies”, dressed as women and assumed effeminate voices and mannerism. They addressed each other as “my dear” and sold unnatural sex to wealthy male patrons. They even enacted, for entertainment, childbirth scenes in which a “molly” delivered a doll at the end of the proceedings.

The Molly Houses were frequented, indifferently, by both intellectuals and randy rascals; they were mostly inner city inns but parties were also held in private houses, the most famous being “Mother Clap’s” in Holborn. It catered, every night, for up to 40 mollies!

England ‘s society was renown to be one of the most tolerant in Europe and it was one where cross-dressing and homosexuality were not just exclusive to the wealthy and bored gentry. It is therefore not surprising to find in such scenario that sexually and morally deviated individuals, after they had come to visit England, were unwilling to return home and choose instead to remain.

One such individual – the Chevalier – is the subject of this essay. He was a Frenchman and a diplomat who, whilst living in London, was even allowed to join the Order of the Freemasons, albeit for all the wrong reasons. His life can be described as extraordinary in every respect and separating facts from fiction in it remains, to this day, still a huge task.

THE EARLY LIFE

Born in Tonnere, Burgundy, on 5th October 1728, D’Eon was baptised with a string of mixed male and females names: Charles Genevieve Louis Auguste Andre’ Thimothee de Beaumont. It was almost as if his life had been sealed with ambiguity from birth!

His father Louis was a penniless lawyer and his mother – Francoise de Chevanson – came from a noble family and stood to inherit a large estate at the birth of a male heir from her union. For unknown reasons Francoise dressed up Charles-Genevieve as a girl and kept calling him Marie for the first seven years of his life, after which Louis took charge of the child and started treating him as a boy. Had Francoise behaved that strangely because she considered her husband unworthy of inheriting her wealth, or had she simply recognised and accepted the effeminate features and nature of her offspring? We shall never know.

Charles-Genevieve was a clever child and at the age of twelve was sent to the College Mazarin in Paris, where he received an education that included the Classics and where he learned to hold himself against the bullies who would target him for his girlish appearance.

At college he also cultivated the art of fencing in which he later excelled and which became the principal passion of his life. Charles-Genevieve was blond, of medium height and slim but with unusually developed breasts and with a pair of small feminine hands and feet.

A document found in the French Foreign Ministry describes him so: “(He) stood out because of his blue eyes, unusual high pitched voice and especially because of his youthful and fresh face complexion”, the latter characteristic being rather rare in an age when the populations were vexed by smallpox, venereal diseases and illnesses of other kind and also suffered from the side effects of the dangerous pot-pourri of chemicals used in the makeup products. Charles-Genevieve left college in August 1748 and a year later he obtained a degree in Common Canon Laws.

A good orator, fluent in foreign languages, excellent in the art of fencing and blessed with an exceptional memory, Charles-Genevieve possessed all the abilities that make a good diplomat and an excellent spy. Soon he was brought to the attention of King Louis XV who recruited him in his personal secret service called “Le Secret du Roi”. It was a private network of spies who answered solely to the King.

THE POLITICAL SITUATION IN RUSSIA

Since 1684 Russia had been co-jointly ruled by Peter the Great and his brother Ivan V. After the death of the former, his brother became the sole sovereign of all Russia in 1696. But when the latter also met his maker in February 1725, it was Anna Ivanovna [1] – Duchesse of Courtland [2] and second daughter of Ivan V – who became Empress of Russia over the head of her cousin Elizabeth Petrovna[3].

Elizabeth was the young daughter of Peter – who had been the real artificer of Russia’s greatness – and thought the she was the rightful heir to the throne. When she discovered in 1740 that she was again going to be overlooked by Anna’s choice of heir in Ivan de Brunswick [4],she begun to plot. A year later, aided by two hundred faithful grenadiers, Elizabeth stormed the Royal Palace and declared herself Empress of all Russia.

Meanwhile in France Louis XV was being concerned by the fate of Poland, the Country of birth of his Queen, on whose throne he was hoping to place his cousin the Prince de Conde and thus take that geopolitical area away from Russia’s control.

Elizabeth had always been an admirer of France and liked its Ambassador, M. De La Chetardie. But when the pro-England Chancellor, Alexis Bestucheff, intercepted a letter in which De La Chetardie criticised Elizabeth, all Frenchmen were barred from Court.

The way things were shaping up in Europe, Russia had to be prevented from aligning itself with England or it would have become too strong an adversary. It was imperative that France retained someone at the Court of Saint Petersburg who would report back on any political and military development; but after Bestucheff’s exclusion order, only French females were allowed in the presence of the Tsarina. This was a setback for France‘s intelligence but not for King Louis XV whose next move proved to be a stroke of genius!

Fully aware of the physiognomies and brilliant social skills of Charles-Genevieve, the King sent him on a mission to Russia in a female role, to play the part of the clever and flirting Lea de Beaumont. D’Eon won the trust of the frail forty-six years old Tsarina and persuaded her to write a letter to her cousin King Louis XV in which she promised to continue supporting France. With that accomplished, D’Eon returned to Paris and personally delivered that letter to Louis XV, expecting some recompense in return. But the King ignored him and, instead, sent him straight back to St. Petersburg to continue the negotiations. Except that this time Charles-Genevieve D’Eon was to play the part of Lea de Beaumont’s own brother (or uncle, some say) as the Secretary to the French Ambassador!

D’Eon’s permanence in Russia lasted a total of four years and required a number of return trips to Paris together with a long and extenuating game of cross-dressing; D’Eon had to appear as Lea de Beaumont when she attended the Russian Court and himself when he had to report matters to the French Ambassador.

In the end a treaty between England and Russia was never signed, much to the satisfaction of Louis XV!

Charles-Genevieve D’Eon’s last trip from St Petersburg to Paris took place in 1760. He was feeling exhausted and with his health weakened by his repeated extenuating journeys and the stressful game of spying , fell seriously ill with smallpox just outside Paris. The King realized it was time to withdraw the character of Lea Beaumont

character of Lea Beaumont from stage and he retired Charles-Genevieve from his private spy network. The cross-dressing game had been going on for too long and now that D’Eon had been struck by an illness that would have, no matter how superficially, scarred his face and body for life, the risk of detection had increased exponentially. Louis appointed D’Eon captain of his elite troops the Dragoons, and sent him to fight with them in the Severn Years War that was raging in Europe. Perhaps D’Eon’s detractors were hoping that the effeminate but brilliant individual would have found life difficult on the battlefields and in the war camps. Hopefully he could have been killed or he would evaded the responsibilities and rigors of military action by fleeing abroad to live incognito.

But despite all expectations Charles-Genevieve distinguished himself in battle – D’Eon was wounded a number of times – and later he even displayed great skills in conducting the diplomatic role that he played in the Anglo-French peace negotiations.

It was the year 1761. This time King Louis rewarded D’Eon with a handsome sum of money and retired him from the Dragoons. D’Eon’s military career was over, much to his displeasure. But in the meantime the political European events had begun to take a different turn!

LONDON

By the year 1762 France was bankrupt and had lost most of its colonies to the English who were ruled by the Hanoverian King George III. Elisabeth of Russia had died and had been succeeded by Peter of Holstein [5] who reversed all her policies and allegiances. Louis XV wanted to have peace and in order to know England’s intentions with regards to the negotiations he sent D’Eon to London as the Secretary of the French Ambassador, the Duke de Nevers or Nivernais [6]. Both men arrived in September of 1762.

According to D’Eon, His Majesty’s undersecretary Mr Wood – who was said to be very fond of the wine from Burgundy – naively accepted the Duke’s invitation to dine at the French Embassy one night. Nivernais was just another character considered to have very little manhood.

On his arrival in England the newspapers had sarcastically commented that France had sent “a preliminary of a man to conduct the preliminary negotiations”.

By now the dinner at the French Embassy , to which even the cross-dresser D’Eon took part , appears as some excuse licentious games to take place , albeit it was undoubtedly accompanied by some very good food and by an interrupted flow of the excellent Burgoigne wine , Tonnere. D’Eon recorded in his memoirs that whilst the meal was being consumed’ , he noticed in Mr Wood’s diplomatic bag an official document of great importance. Taking advantage of the situation in which the inebriated English diplomat and the Duke were engaged, he copied the missive and dispatched it to Versailles on the following morning. That document detailed the way England intended to conduct the peace negotiations and it proved to be of an extraordinary importance for France.

King Louis XV this time rewarded D’Eon with a life annuity and invested him with the Cross of Saint-Louis which gave the right to call himself “Chevalier”, the equivalent of “Sir”.

After the treaty of Paris[7] was signed in 1763, the King appointed the aristocrat de Guerchy as the new France Ambassador to London. Nivernais was recalled and D’Eon was sent to London with the title of Ministre Plenipotentiary, to manage the Embassy whilst awaiting the arrival of the Comte de Guerchy.

DISMISSAL

The Comte de Guerchy was from Burgundy like D’Eon and a wealthy nobleman. He was a snobbish, mean and ambitious man who had been nominated Ambassador by the King only on the insistence of Madame de Pompadour who was jealous of and wanted him disgraced. Charles-Genevieve would later describe Guerchy as and individual: “timid in war, brave in peace, ignorant in the City, tricky at Court, generous with other people’s money but stingy with his own” [8] .

The two men never got on well together and became mortal enemies. To expect that they should work closely together was pure illusion.

D’Eon arrived in London in May 1763 and immediately started acting as if he was the Ambassador for France.

Both Charles-Genevieve and his imaginary sister Lea de Beaumont soon became regular and welcomed visitors at the English Court although, for obvious reasons, they never made an appearance together. D’Eon even spent long evenings in the company of Queen Charlotte as her French reader and always wore the Cross of Saint-Louis on his female dresses. D’Eon also organised galas at the French Embassy, bought expensive wines, took on servants. In short, he lived on a grand scale whilst earning only 25,000 livre. He worked zealously and at all hours of day and night. He did so only for the love and interest of France, often at the cost of his own health; but when he fell in debt by 20,000 livres and asked the French Ministry for a refund, his letters went unanswered. In contrast to D’Eon’s salary, Guerchy’s emoluments as Ambassador had been set at 150,000 livres a year plus another 50,000 for gratuities. For D’Eon this represented an injustice and an insult and in retribution he continued spending lavishly. Except that he would no longer use his own money, but that from the French Embassy’s chest.

When Louis XV officially wrote to George III to inform him that D’Eon was being removed from his diplomatic post – which to D’Eon meant the loss of his title of Ministre Plenipotentiary with all the privileges that came with it – and that the Comte de Guerchy was to take charge of the Embassy’s affairs, Charles-Genevieve realised that, for his safety, he needed to double play.

He left his apartment at the Embassy and retrieved in a house in Dover Street with all his secret and important correspondence, refusing to return to France as he had been ordered. He never accepted that he had de facto been “deposed” as Ministre Plenopotentiary. The “Ordre de Congede” bore a royal stamp but not the King’s original signature and D’Eon considered it to be a fake for as long as he lived. He believed that the document had been forged by Guerchy himself.

One day, whilst Guerchy was away, D’Eon had dined at the Embassy and fallen ill for two lengthy weeks. He believed that an attempt to poison him had been perpetrated and when he discovered that his locksmith had taken an impression of the locks of his Dover Street residence, he suspected that kidnapping was also on the cards. In a letter to King Louis XV D’Eon wrote: “Subsequently I discovered that M. Guerchy caused opium – if nothing worse – to be put in my wine, calculating that after dinner I should fall into a heavy sleep onto a couch and instead of my being carried home, I should be carried down to the Thames where probably there was a boat waiting ready to abduct me”.

For the next six year D’Eon went to live at 38 Brewer Street, Golden Square and kept his secret documents locked up in the basement, constantly guarded by some faithful grenadiers who had fought with him in the Dragoons. He mined the rooms and he kept a lamp burning day and night to show that the premises were constantly occupied. When the King of France wrote to George III to ask him to seize those papers from D’Eon, the Chevalier openly complained of his treatment to a number of his influential friends. But nobody helped him and he decided to retaliate. He gathered all his secret documents and correspondence – minus France’s plans to invade England, of course – and published them in a book which he called “Lettre , memoires et negotiations particulieres”. It became a best seller in Europe and made the Chevalier famous.

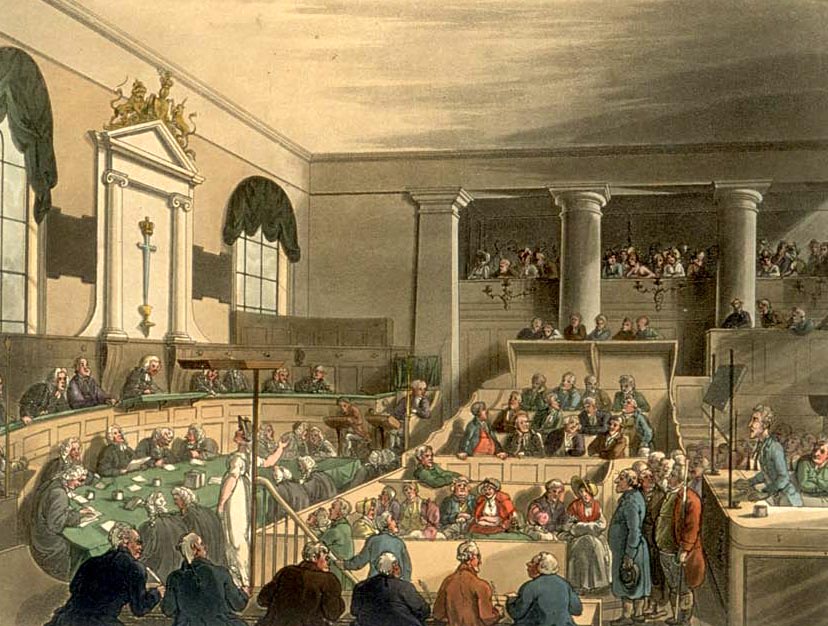

Although for different reasons – D’Eon accused Guerchy of attempted poisoning and Guerchy accused D’Eon of libel – they both began litigation in Court and both lost. But whereas Guerchy was able to call upon his diplomatic indemnity and carry on with his official duties, it cost D’Eon an exile from France of fifteen years.

D’EON AND WOMEN IN FREEMASONRY

Whilst he lived in London, Charles-Genevieve was initiated into Freemasonry in May of either 1766 or 1768. He joined the London based French speaking “Loge de l’Immortalite de l’Ordre” also known as the “Lodge of Immortality No. 376”, which met at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand. The records show that he served the office of Junior Warden in the Masonic year 1769-70.

Charles-Genevieve joined the Order because he was searching for a safe heaven from a society that was pushing him to a reclusive life but also to seek protection from France’s repeated plots to have him killed or kidnapped.

D’Eon always mentioned the Craft in a most flattering manner and there are many portraits of him dressed in female attire, wearing both the Freemason’s apron and the Cross of St Louis. However the initiation of by the Moderns in the Masonic Order, gave the traditional Ancients Freemasons room for ample criticism. The Modern’s practice of “initiating women” was seen as a clear sign of extravagance and allowed the Ancients to claim that they were the only faithful preservers of the traditional usages and customs of Freemasonry.

But the phenomenon of women joining Freemasonry was nothing new. From the early part of the 18th century women had attempted to be initiated or to obtain  the secrets of Freemasonry. The Grand Lodge of Scotland has posted on its website some of the cases of women who were initiated in the Craft. For example:

the secrets of Freemasonry. The Grand Lodge of Scotland has posted on its website some of the cases of women who were initiated in the Craft. For example:

Case 1 – In 1710 the Viscount Duneraile , a Freemason, was carrying out some repairs to Donaraile Court. One night the Viscount’s daughter, Elizabeth St Leger, awakened by the voices of the masons who were engaged in a meeting, decided to peep through a hole made in the wall , whilst at the same time causing noises herself and be found out. On trying to escape, she was caught by the Tyler and to ensure that the Freemason’s secret did not became public, she was initiated there and then. From thereafter she was sworn to silence.

Case 2- Melrose Lodge No. 1Bis, preserves a tradition that Isabella Scoon “had somehow obtained more light upon the hidden mysteries that was deemed at all expedient and after due consideration, it was resolved that she must be regularly initiated into Freemasonry”. She later distinguished herself for her charity work.

In France, on the other hand, women were freely allowed to join the Order; a tradition that continues to these days. Although the French Brotherhood initially remained within the letter of Anderson’s constitution – which excluded women from joining – it saw no reason to ban women from their banquets or religious services. During the 1740s, there appear to have been Lodges which were attached to regular ones (i.e. for men only) but which allowed women, although those admitted were mainly wives or relatives of Freemasons. The lodges were called Lodges of Adoption and in 1774 they fell under the jurisdiction of The Grand Orient of France. The system was made up of four degrees:

- Apprentie, or Female Apprentice.

- Compagnonne, or Journeywoman.

- Maîtresse, or Mistress.

- Parfaite Maçonne, or Perfect Masoness.

The idea of women Freemasons spread widely in Europe, but whereas the practice never established itself either in England or in America, it flourished in France at the start of the French Revolution. Even Napoleon’s wife Josephine presided over one of those Lodges of Adoption in Strasburg in 1805.

The English Freemasons never forgot D’Eon and allowed him to remain a member even after he had been legally declared a woman. There is evidence that the Master of the London Lodge of the Nine Sisters, who enlisted famous English and foreign respectful characters, invited him to celebrate the departure to the Gran Lodge above of a one of their Brothers.

The Master wrote this note to D’Eon :

“I endorse an invitation to this fete where you have a place reserved for you, as Mason, as belletrist (intellectual) as one who is an honour to her sex after having been an honour to ours. It is permissible only for Mlle to surmount the barrier which forbids access to our work to the most beauteous (charming) half of humanity. The exception begins and finishes with you; do not refuse to enjoy you right” [9]

It is not recorded whether D’Eon ever took part.

THE HELL FIRE CLUBS

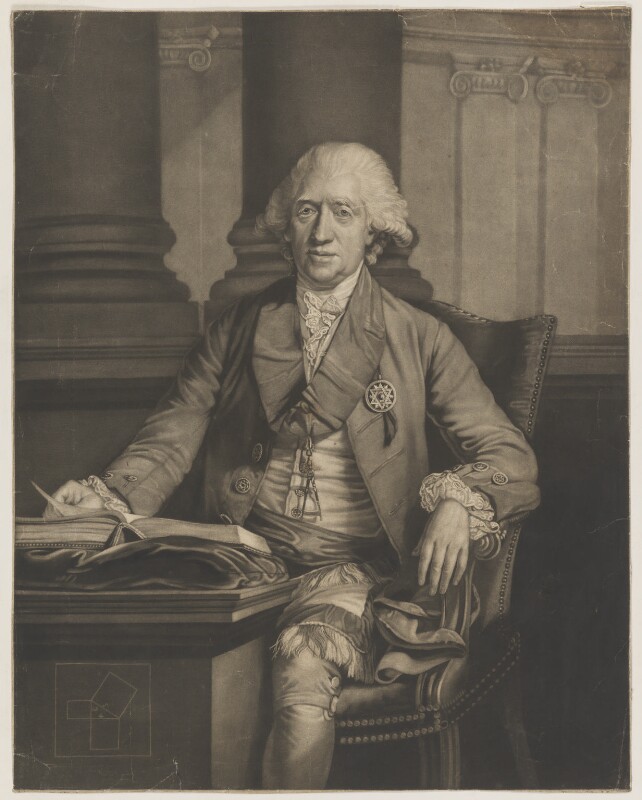

In the 18th century there were a number of clubs in the British Isles which engaged in violent and sometimes murderous pranks. Drinking and whoring were regular activities for their members. The clubs were frequented by Aristocrats as well as by members of the political world and often they also enlisted Freemasons. Indeed it is reported that none other than the Grand Master of the English Grand Lodge from 1722/23 – the Duke of Wharton – had co-founded the first Hell Fire Club in 1719. After Wharton’s Club was closed down by Walpole’s government Proclamation against “obscene” associations in 1721, the Duke set up a so called “Schemers Club” in 1724. The latter being just another assembly of mischievous men who proclaimed themselves dedicated to the “advancement of flirtation”.

There was a Hell Fire Club also in Dublin and it too had been founded by an aristocrat – the 1st Earl of Rossen – another Freemason and Ireland’s Grand Master in 1725. But the most well known of the Hell Fire Clubs was the one called “The Order of St. Francis” , which was founded around 1740s by Sir Francis Dashwood, a member of the Parliament as well as a Freemason.

It met initially in a disused Cisternian Abbey in the village of Medmenham (Buckinghamshire) but later moved to some caves situated above the village of West Wycombe (Buckinghamshire), not far from the Estate of the Dashwoods. Secret meetings and week-end parties are said to have been held in that underground labyrinth of caves which led to a chamber called the Inner Temple , situated directly beneath the local Church of St.Lawrence where mass is still being celebrated on Sundays to these days.

Some of those “Franciscans” were notable Freemasons like John Wilkes, William Hogarth, Benjamin Franklin and our intriguing Chevalier .

The sexual games, orgies and perverted acts that went on in those underground vaults must have appealed to the ambiguous genre of the Chevalier who later had the boldness to claim that he had joined Freemasonry only for a chivalric reasons!

RETURN TO FRANCE

Following the death of Louis XV, D’Eon was recalled to France by his successor Louis XVI who was anxious to gather back all those secret and dangerous documents that the Chevalier had been guarding back in London, as well as removing for good from the scene the embarrassing character of Lea de Beaumont.

But D’Eon dumbfounded France by deciding to blackmail the King. He declared he would not give up any of those sensitive documents – among which were the plans to invade England – unless His Majesty paid him an enormous amount of money and promised to protect him from his enemies. Louis XVI wanted to stop waging wars and heal the financial state of his Kingdom, so in 1775 he sent over his top secret agent Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaunarchais, to negotiate with the Chevalier.

An agreement was reached whereby , when back on France soil, D’Eon would have been publicly and legally declared a woman and be in receipt of a sum of money large enough to pay off all his debts and to provide him with a comfortable living. At the age of forty seven, with a pension and a debt free status, Charles-Genevieve D’Eon deemed himself to live the rest of his life as an individual of the opposite sex; but at least he could again attend the French Court and be allowed in the company of the Queen Marie Antoinette. Indeed the Queen even helped Charles-Genevieve with the choice of a female wardrobe, his wigs and make up. D’Eon lived in Versailles for many years and whilst there he wrote his autobiography: “La vie militaire, politique et privee de Mademoiselle ”.

However when France joined the American War of Independence against the English, D’Eon’s love for the military life resurfaced and he wrote to the French Minister for permission to re-enter service. He was immediately arrested and put into a dungeon from where he was released only after he solemnly promised never to wear male clothes again, abandon Versailles and return to his home in Tonnerre, Burgundy, to live with his mother.

Yet in 1785, D’Eon appeared once again to betray his promise and he was seen riding in his estate dressed in a dragoon uniform. The King, noting Charles-Genevieve’s restlessness and unwillingness to settle down in an anonymous life, decided to send him back to England to continue the work of gathering and returning to France his compromising documents. This time, however, D’Eon never returned to France. It was the dawn of the French Revolution and he did not share those ideals, nor would anyone who saw all of his friends guillotined by the Jacobins !

Furthermore, the Revolution deprived him of his annuity and he had to spend seven months in prison for debts.

On his return to London in 1785 , D’Eon had declared that England was “a Country more free (sic!) than Holland and well worth visiting by any man (who is) a lover of liberty. …” and libertinage, I would add!

He had returned as Lea de Beaumont and was never to dress as a man again. He had made his final choice of gender and perhaps done so at the wrong time of his life, when his voice had turned deep and cavernous and his mannerism vulgar and noisy. The writers Horace Walpole and James Boswell were never taken in by feminine attire and portrayed him as a transvestite, a cross-dresser ante litteram in total contrast to the great philander Giacomo Casanova who wrote in his memoirs: “It was at that ambassador’s table that I made the acquaintance of the Chevalier , the secretary of the embassy, who afterwards became famous. This Chevalier was a handsome woman who had been an advocate and a captain of dragoons before entering the diplomatic service; she served Louis XV as a valiant soldier and a diplomatist of consummate skill. In spite of her manly ways I soon recognized her as a woman; her voice was not that of a castrato, and her shape was too rounded to be a man’s. I say nothing of the absence of hair on her face, as that might be an accident.”

Later on in his memoirs the great lover took the opposite view and recounted the story of a 20,000 guinea bet placed on the gender of the Chevalier. The bet was never either won or lost because the Chevalier refused to be examined.

LATER YEARS

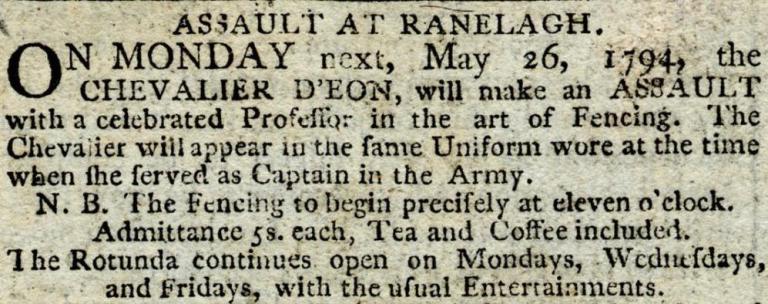

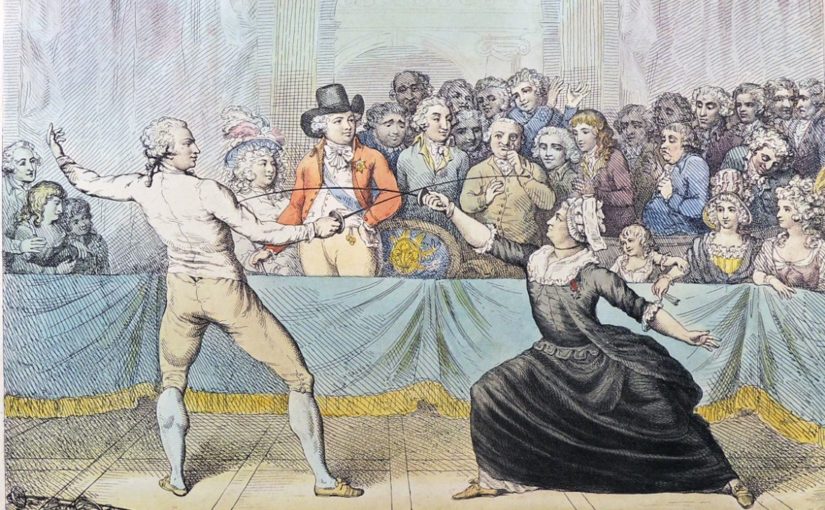

D’Eon supported his income whilst living in London by challenging men at duel for monetary prizes. On April 9th 1787, at Charlton House, Lea Beaumont confronted a French sword champion twenty years his younger and won. The publicity he gained from that event enabled him to set up a successful fencing Academy which toured the Country and performed in packed public halls.

Life was again good to Charles-Genevieve until on a tragic day at Southampton in August 1796, an opponent wounded him and made him bedridden for two long years.

D’Eon never recovered from that mishap and spent the last years of his life in misery and poverty, sharing a house with a Mrs Mary Cole, an admiral’s widow he had met in 1795. D’Eon passed away peacefully in his bed on May 21 1810 having spent forty nine years of his life passing as a man and thirty three as a woman. At his death, Mrs Cole’s priest – Father Elysee – made the following account of the body of the Chevalier as he laid on the bed:

“The body presented unusual roundness in the formation of the limbs; the appearance of a beard was very slight, and hair of so light a colour as to be scarcely perceptible was on the arms, legs and chest. The throat was by no means masculine; shoulders square and good; breast remarkably full; arms, hands, fingers those of a stout female….and she has a cock”.

Later on a cast was taken of his body and a thorough examination carried out in the presence of the Prince de Conde, the Earl of Yarmouth Sir Sidney Smith and a number of surgeons, lawyers and former regimental friends of D’Eon . Afterwards, the witnesses signed a declaration that certified that “the body is constituted in all that characterises man , without any mixture of sex”.

How mystifying !

Charles-Genevieve ‘s body was buried in St Pancras’s cemetery and his tombstone is still present there today.

It is curious to note that now the phenomenon of transgenderism is in the open, a Society called “The Beaumont Society” has been set up in UK to support the cross-dressing and transsexual’s community. In its website it is stated that the Society “keenly promotes the better understanding of the conditions of transgender, transvestism and gender dysphoria in society, thereby creating and improving tolerance and acceptance of these conditions by a wider public.” The same tolerance that even the United Grand Lodge of England has displayed by declaring in August 2018 that if transgenders had joined the Order as men, they should be allowed to remain Freemasons. The UGLE’s guidance warns that using a mason’s transition as a reason for excluding him/her from a man-only Lodge, would constitute “unlawful discrimination”. A decision that only time will tell whether it has been harmful to the image of the Order and cause it a downfall.

The Chevalier told the world that he was a woman who had disguised herself as a man. In fact he was a man pretending to be a woman who was now admitting to be a man. – by Richard Bernstein, New York Times

By W.Bro. Leonardo Monno Anglisani – IPM of NHL 6557 in the Prov. of Middlesex, England

The author forbids any reproduction or publication of this article, in full or in part, without his explicit authorization.

[1] Moscow 7/2/1693 – St Petersburg 28/10/1740 [2] Now western Latvia [3] Moscow 29/12/1709 – St Petersburg 5/1/1762 [4] Anna Ivanovna ‘s German grandnephew. Born in Saint Patersburg 23.08.1740, he died in Shisselburg 16.07.1764. Only two months old when he was proclaimed Emperor and after Elizabeth Ivanovna seized power in 1741 he was put into prison and killed twenty three years later, whilst still confined. [5] Born in Kiel in the Dukehy of Holstein in February1728 and died in July 1762 in Ropsha. He reigned as Peter III, Emperor of Russia for only six months in 1762. [6] Louis-Jules Barbon Mancini-Mazarin, Duke de Nevers (16 December 1716 – 25 February 1798) [7] The Treaty of Paris in 1762 ended the Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the United States, recognized American independence and established borders for the new nation. [8] Royal Spy by Emma Nixon, page 80 [9] « La Femme du Grand Conde’ » by Octave Homberg et Fernand Jousselin and a mentioned by Edna Nixon in « Royal Spy » page 222.

Sources - “Royal Spy” by Emma Nixon - “Initiation in male Lodges” – Grandscottishlodge.com - “The strange destiny of the Chevalier ” by Wm E. Parker – The Northern Light magazine, June 1983 - “Hell Fire and Freemasonry” – angelfire.com - “Sir Francis Dashwood “by David Harrison, The Square magazine, March 2014 - Noonobservation.com - BeaumontSociety.org.uk - Gay.it/cultura - Lastampa.it/2006/08/17/cultura

despite the fact that he was one of the most glittering figures of one of the spectacular periods of human history. There are few characters of the time of which so much is recorded but who are so little remembered. As the stories of the first and second Temples form the basis of the Craft and the Royal Arch it is perhaps surprising that the story of the “Third Temple” – for, that is what it really was – and its builder, has never been told in Freemasonry.

despite the fact that he was one of the most glittering figures of one of the spectacular periods of human history. There are few characters of the time of which so much is recorded but who are so little remembered. As the stories of the first and second Temples form the basis of the Craft and the Royal Arch it is perhaps surprising that the story of the “Third Temple” – for, that is what it really was – and its builder, has never been told in Freemasonry. Zerubbabel, and the rest, but also Herod?

Zerubbabel, and the rest, but also Herod?

hijo de Carlos IV, que había sido depuesto por el gobierno francés, y ellos obligó al virrey a abdicar. Por lo tanto, Venezuela fue el primero Colonia de España para declarar su independencia, un evento que tomó coloque el 5 de julio de 1811.

hijo de Carlos IV, que había sido depuesto por el gobierno francés, y ellos obligó al virrey a abdicar. Por lo tanto, Venezuela fue el primero Colonia de España para declarar su independencia, un evento que tomó coloque el 5 de julio de 1811. General José de San Martin, un masón, y el general Bemardo O`Higgins, también un masón, tenían liberó a Argentina y Chile del poder español, y el primero, ahora “Protector” de Perú, llegó a Guayaquil el 26 de julio de 1822, donde él consultó con Bolívar. Qué procedimientos se decidieron, con respecto a Perú, en esa conferencia entre los dos grandes Los Líberators españoles, que eran masones, probablemente nunca ser conocida. San Martín renunció a su ‘Protectorado” de Perú y regresó a Argentina. En cualquier caso, Bolívar se hizo cargo y, llegando en Callao, el 1 de septiembre de 1823, fue investido con el título de “Libertador” de Perú. Entrenó a unos 4,000 peruanos y, con el ejército que había venido a Perú con él, tenía unos 9,000 hombres. Con estos contrató a un número igual de españoles en Junin en una sangrienta batalla de caballería con sables, donde no se disparó un solo tiro, y ganó un victoria que, con la de Ayacucho el 9 de diciembre dc 1824, bajo El general Antonio José de Sucre, terminó para siempre con el poder colonial de España en el Nuevo Mundo

General José de San Martin, un masón, y el general Bemardo O`Higgins, también un masón, tenían liberó a Argentina y Chile del poder español, y el primero, ahora “Protector” de Perú, llegó a Guayaquil el 26 de julio de 1822, donde él consultó con Bolívar. Qué procedimientos se decidieron, con respecto a Perú, en esa conferencia entre los dos grandes Los Líberators españoles, que eran masones, probablemente nunca ser conocida. San Martín renunció a su ‘Protectorado” de Perú y regresó a Argentina. En cualquier caso, Bolívar se hizo cargo y, llegando en Callao, el 1 de septiembre de 1823, fue investido con el título de “Libertador” de Perú. Entrenó a unos 4,000 peruanos y, con el ejército que había venido a Perú con él, tenía unos 9,000 hombres. Con estos contrató a un número igual de españoles en Junin en una sangrienta batalla de caballería con sables, donde no se disparó un solo tiro, y ganó un victoria que, con la de Ayacucho el 9 de diciembre dc 1824, bajo El general Antonio José de Sucre, terminó para siempre con el poder colonial de España en el Nuevo Mundo .Habiendo planeado estas batallas con el general Sucre, un masón, Bolívar fue a Lima para organizar un gobiemo cívico y llamar a un Convención Constitucional. Cuando, el 8 de febrero de 1825, tuvo efectuado el nuevo gobierno, renunció al poder supremo en Colombia y Perú. Rechazo de un regalo de 1,000,000 de pesos (aproximadamente $200,000) de Perú y por haber asistido a algunos asuntos cívicos en Perú superior (Bolivia), Bolívar dejó al general Sucre a cargo y se dirigió a Bogotá, Colombia, para calmar los conflictos civiles que habían surgido entre sus antiguos camaradas. Al llegar allí en noviembre de 1826, él pronto pasó a Venezuela, convocando una convención constitucional en ruta para reunirse en Valencia, el 15 de enero de 1827. Aunque él no tuvo sido capaz de ajustar la desafección, ingresó a Caracas en triunfo. Finalmente, después de catorce años en el mando supremo. La renuncia de Bolívar fue aceptada por el Congreso a petición suya, frente a la intriga y el abuso de sus enemigos que fueron hambriento de poder.

.Habiendo planeado estas batallas con el general Sucre, un masón, Bolívar fue a Lima para organizar un gobiemo cívico y llamar a un Convención Constitucional. Cuando, el 8 de febrero de 1825, tuvo efectuado el nuevo gobierno, renunció al poder supremo en Colombia y Perú. Rechazo de un regalo de 1,000,000 de pesos (aproximadamente $200,000) de Perú y por haber asistido a algunos asuntos cívicos en Perú superior (Bolivia), Bolívar dejó al general Sucre a cargo y se dirigió a Bogotá, Colombia, para calmar los conflictos civiles que habían surgido entre sus antiguos camaradas. Al llegar allí en noviembre de 1826, él pronto pasó a Venezuela, convocando una convención constitucional en ruta para reunirse en Valencia, el 15 de enero de 1827. Aunque él no tuvo sido capaz de ajustar la desafección, ingresó a Caracas en triunfo. Finalmente, después de catorce años en el mando supremo. La renuncia de Bolívar fue aceptada por el Congreso a petición suya, frente a la intriga y el abuso de sus enemigos que fueron hambriento de poder.

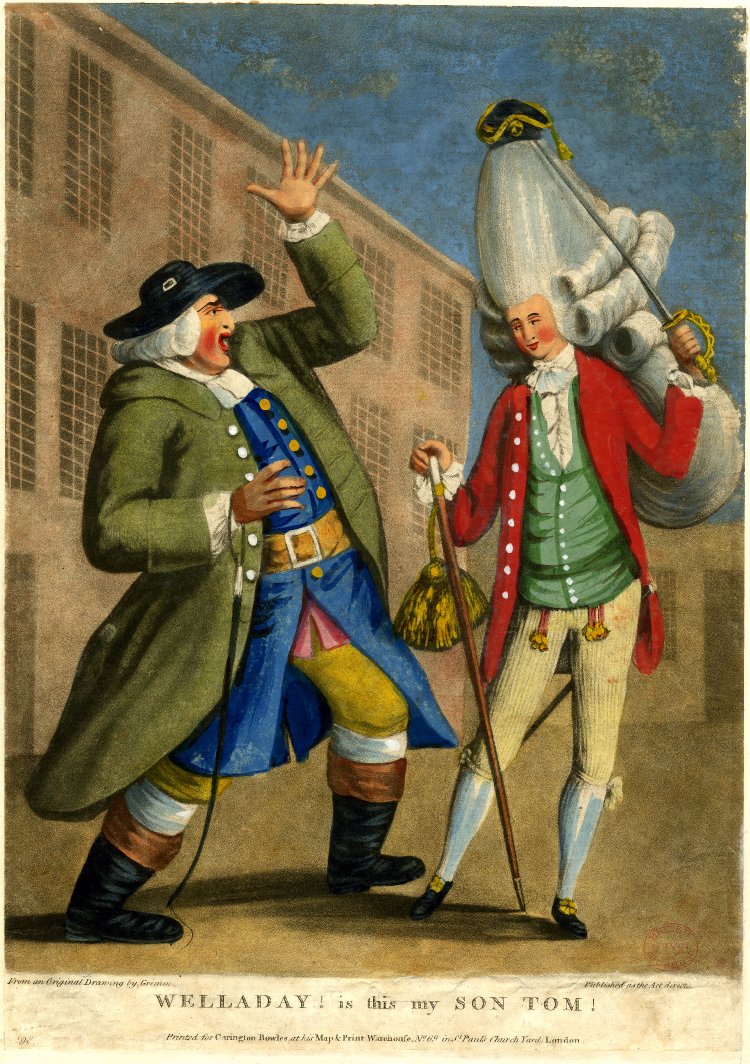

as “a fashionable fellow in the mid-18th-century England who dressed and even spoke in an outlandishly affected and epicene manner” and also as a person “who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion in terms of clothes, fastidious eating and gambling”.

as “a fashionable fellow in the mid-18th-century England who dressed and even spoke in an outlandishly affected and epicene manner” and also as a person “who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion in terms of clothes, fastidious eating and gambling”. Earl of Chesterfield

Earl of Chesterfield With no lawyer to defend him, he pleaded for mercy with the Court and delivered a speech from which we have extracted the following:

With no lawyer to defend him, he pleaded for mercy with the Court and delivered a speech from which we have extracted the following: to visit the garden of the school of Ashbourne; a very pretty place on a bank of the river. It was a hot day and they sat on a bench for a little rest, whereupon Johnson – Boswell reports in his diaries – told him of his “humane interference” on behalf of the Rev. Dr Dodd whom he barely knew. Knowing Johnson’s persuasive power of writing Dodd had asked him, through the interception of the late Countess of Harrington, to employ his pen in his favour by writing a letter of supplication to the King so that “(the King) may spare me the ignominy of public death which the public itself is solicitous to waive, and grant me in some distant part of the globe to pass the remainder of my days in penitence an prayer (…)”.

to visit the garden of the school of Ashbourne; a very pretty place on a bank of the river. It was a hot day and they sat on a bench for a little rest, whereupon Johnson – Boswell reports in his diaries – told him of his “humane interference” on behalf of the Rev. Dr Dodd whom he barely knew. Knowing Johnson’s persuasive power of writing Dodd had asked him, through the interception of the late Countess of Harrington, to employ his pen in his favour by writing a letter of supplication to the King so that “(the King) may spare me the ignominy of public death which the public itself is solicitous to waive, and grant me in some distant part of the globe to pass the remainder of my days in penitence an prayer (…)”. Boswell was expressing his full of admiration for the determination with which Dodd had met his creator a few days earlier. “Dr Dodd seemed to be willing to die and was full of hopes and happiness”, said Boswell. But Johnson retorted that hardly any man dies in public with apparent resolution: “Sir” –said Johnson – “Dr Dodd would have given both his hands and both his legs to have lived because the better a man is, the more afraid is he of death, having a clear view of infinite purity”.

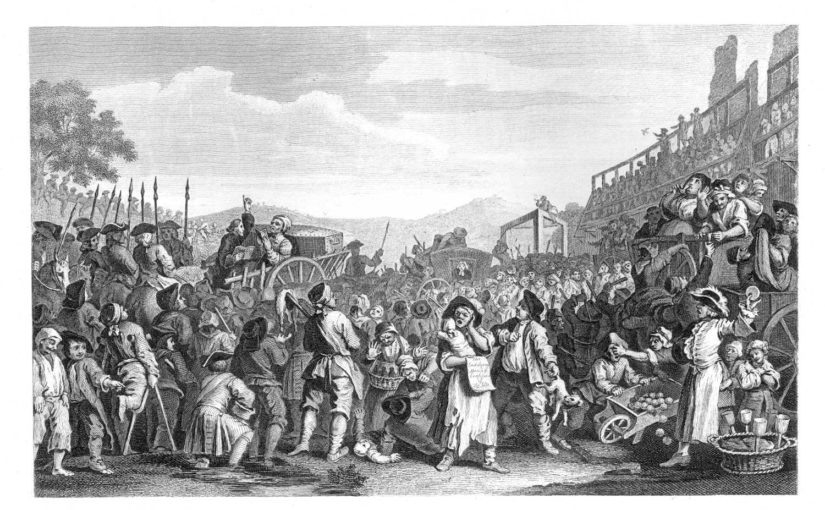

Boswell was expressing his full of admiration for the determination with which Dodd had met his creator a few days earlier. “Dr Dodd seemed to be willing to die and was full of hopes and happiness”, said Boswell. But Johnson retorted that hardly any man dies in public with apparent resolution: “Sir” –said Johnson – “Dr Dodd would have given both his hands and both his legs to have lived because the better a man is, the more afraid is he of death, having a clear view of infinite purity”. The death-by-hanging technique improved only in the 20th century when mathematical formulas begun to be applied to determine the length of the rope and the height of the drop required to break the person’s neck, quickly. But in the days when such factors – height, weight and neck size of the condemned – where never taken into consideration , the condemned’ s death would have occurred only by a long and inhumane process of strangulation.

The death-by-hanging technique improved only in the 20th century when mathematical formulas begun to be applied to determine the length of the rope and the height of the drop required to break the person’s neck, quickly. But in the days when such factors – height, weight and neck size of the condemned – where never taken into consideration , the condemned’ s death would have occurred only by a long and inhumane process of strangulation.

Although the Navy did not provide an apprenticeship leading up to an independent trade, it gave long-term employment to those who were fit and healthy. The Navy recruited from a wide spectrum of the society and even practiced impressment, a custom of forcing any men of age 18 and upwards to serve the Nation for a specific time and in situations of war, even against their will. Many such individuals and children stayed on and progressed through the ranks , reaching captaincy and receiving commissions . A few even ended their service as Admirals.

Although the Navy did not provide an apprenticeship leading up to an independent trade, it gave long-term employment to those who were fit and healthy. The Navy recruited from a wide spectrum of the society and even practiced impressment, a custom of forcing any men of age 18 and upwards to serve the Nation for a specific time and in situations of war, even against their will. Many such individuals and children stayed on and progressed through the ranks , reaching captaincy and receiving commissions . A few even ended their service as Admirals.

Destined to become one of the most romantic figures in the history of Freemasonry, Andrew Michael Ramsay was born in Ayr, Scotland, on June 9th 1686. He entered Edinburgh University at the age of 14 and studied classics, maths, theology and on finishing his studies he took up the position of tutor in the Earl of Wemyss’

Destined to become one of the most romantic figures in the history of Freemasonry, Andrew Michael Ramsay was born in Ayr, Scotland, on June 9th 1686. He entered Edinburgh University at the age of 14 and studied classics, maths, theology and on finishing his studies he took up the position of tutor in the Earl of Wemyss’ England after losing the crown to the protestant Prince William of Orange. From 1725 to 1728, Ramsay stayed as an invited guest of the Duc de Sully and it was during this period he wrote the famous novel The Travels of Cyrus which was published in 1727. It was a best seller in its day and served to establish the Chevalier’s reputation in England as well as on the Continent.

England after losing the crown to the protestant Prince William of Orange. From 1725 to 1728, Ramsay stayed as an invited guest of the Duc de Sully and it was during this period he wrote the famous novel The Travels of Cyrus which was published in 1727. It was a best seller in its day and served to establish the Chevalier’s reputation in England as well as on the Continent.

In the crypt of the Sansevero Chapel in

In the crypt of the Sansevero Chapel in