Among the interesting characters that populated Georgian England and spiced it with many anecdotes is the Rev. Dr. William Dodd [1] ; a clergyman with a very unmistakable nickname whose weakness in money matters sent him to the gallows for the crime of forgery on 27th June 1777.

His life history resembles a middle-class melodrama and is a fascinating reading.

———– ~~~~~~~ ———–

William Dodd was born in Bourne, Lincolnshire, in 1729, the son of the local vicar. He attended the University of Cambridge from 1745 to 1750 and achieved academic success by graduating with first class honours. He then moved to London where he impulsively married Mary Perkins, the daughter of a penniless domestic servant, on 15th April 1751. To secure his family a steady income, William took the holy orders in 1771. Two years later he was ordained priest and thereafter his career in the Church took him to serve as a Curate and a preacher of some success.

He devoted a lot of his time to charitable work and is accredited to have written over fifty books. However he also mixed with friends of dubious reputation and infamous public fame such as the Freemason John Wilkes, a member of the Parliament who had been arrested for his radical political ideas and for his opposition to George III.

In 1763 Dodd became the vicar of Chalgrave and three years later he gained a doctorate in law from Cambridge University.

The other offices that he filled in life were: Honorary Canon of Brecon, Rector of Hocliffe, King’s Chaplain in Ordinary and tutor to Philip Stanhope who later became the 5th Earl of Chesterfield. All these various church and academic appointments rewarded him with a good income, but Dodd lived well beyond his means and money was always in short supply.

In 1774 Dodd, in an attempt to bolster his earnings, endeavoured to bribe Lady Apsley, the wife of none other than the Lord Chancellor! He had incautiously offered her £ 3,000 if she would secure him the appointment as Rector of St George’s, Hanover Square, London. In those days Vicars could be in control of more than one Church and so tot up their salary.

The dishonourable proposition to Lady Apsley proved fatal for the fortunes of the Reverend Dodd as it led to the dismissal from all his academic and religious positions and compelled him to flee abroad.

His exile lasted two years and was made the more unbearable by the fact that whilst he was spending time in foreign lands – Switzerland and France – he was regularly being made an object of public ridicule in London by the dramatist and actor Samuel Foote who taunted him as the character Dr Simony in a play he staged at the Haymarket Theatre.

WILLIAM DODD THE FREEMASON

It is bizarre to notice that in Georgian England whenever an individual of some reputation became the target of defamation, the recipient of life threats or had his freedom restricted by accusation of unlawful behaviour, Freemasonry would step in to offer protection, support and sometime even rehabilitation.

As a matter of fact, nothing strange was taking place because, as far as the Craft was concerned, it was applying its principle that “he who is on the lowest spoke of fortune’s wheel, is equally entitled to our regard”.

Therefore what William Dodd decided to do at that point of his life and on his return to England in 1755, was no more unusual than what many of his contemporaries in similar situations were doing: he joined Freemasonry.

Dodd was initiated into the St. Albans Lodge No. 29 where, after briefly occupying the office of Junior Deacon, he rose to the rank of Grand Chaplain of the Order and in May 1755, on the occasion of the laying of the cornerstone for the Grand Lodge of England in Queen Street, London, the Rev. Dr. William Dodd even delivered an oration which was widely pubblicised.

The St Alban’s Lodge [2] had been founded in 1728 and was meeting at the Castle and Leg Tavern in Holborn, London. Today it is one of nineteen Lodges that have received the privilege by Grand Lodge of nominating one of its members – every year – to the office of “Grand Steward”. It has therefore become known as a “Red Apron Lodge”.

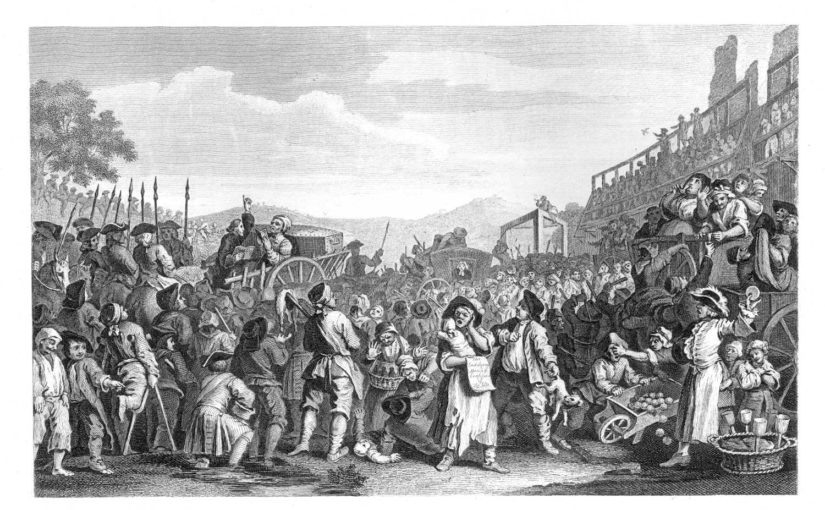

THE NICKNAME OF THE MACARONE PARSON

Dodd’s constant presence at the race horse tracks had made him a well known public figure and the extravagant style of his clothes, led him to become known as “The Macarone Parson”!

Some sources describe the Macarone  as “a fashionable fellow in the mid-18th-century England who dressed and even spoke in an outlandishly affected and epicene manner” and also as a person “who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion in terms of clothes, fastidious eating and gambling”.

as “a fashionable fellow in the mid-18th-century England who dressed and even spoke in an outlandishly affected and epicene manner” and also as a person “who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion in terms of clothes, fastidious eating and gambling”.

But the Macarone was also the caricature of an upper-class effeminate practitioner of sodomy, recogneasable by an extravagant hairstyle, effeminate mannerism and the small tricorn hat that he wore on top of a big wig. The early 1770s saw a series of scandals in the fashionable circles of London society that further linked the term of Macarone to a queer inclination and the homosexual man. A certain Captain Robert Jones, a “Macarone” , was convicted in July 1772 at the Old Bailey for sodomizing a thirteen-year-old boy and was sentenced to hang in October. A letter published in The Public Ledger on August 5th 1772, warned those men like the Captain : “(…) therefore, ye Beaux, ye sweet-scented, simpering He-She things, deign to learn wisdom from the death of a Brother”.[3]

But Jones obtained a royal pardon on the condition that he left the country after new evidence suggested that the boy’s testimony may have been unreliable. The pardon was of course greeted with accusations of an establishment cover-up.

Which of the above two mentioned categories of men – the fashionable fellow or the effeminate molly – our Reverend Doctor belonged to, however, can only be speculated on.

THE REVEREND DODD’S CRIME

By 1776 Dodd was living in Argyle Street, London and was regularly in need of money.

Years earlier he had been the tutor of the current 5th Earl of Chesterfield who had just come of legal age ; this gave Dodd the idea of defrauding a large sum of money by borrowing it in the name of his former pupil.

He went to a money broker and told him that the Lord urgently needed funds whilst he was in waiting for his inheritance to come through. However the Lord – explained Dodd – desired to keep the transaction private and had authorised him to conduct the negotiations.

The means of financing the loan was by a Bond issued in the Earl’s name. Being a man of the Church and a former tutor of the aristocrat, Dodd thought nobody would suspect the arrangement to be a fraud. He also no doubt flattered himself to believe in his heart that the Lord, warm of his feeling towards him, would have generously paid the money rather than see Dodd suffer the dreadful consequences of violating the law.

But finding Banks or individuals prepared to lend against a Bond that was not going to bear the actual borrower’s signature and was not going to be witnessed either, was proving difficult.

Even though forgery and fraud carried a sentence of death by hanging in those days, many fortunes were lost and many gained through such games of tricks.

Eventually the Broker Lewis Robertson came forward and persuaded the firm of solicitors Messrs Fletcher & Pitch to advance the sum of money. A bond was drafted in the name of the Earl of Chesterfield and released to Lewis Robertson who passed it on to Dodd.

The Reverend affixed his signature where that of the Lord should have been , the broker endorsed it further by placing his own signature under that of Dodd and the money changed hands.

Except that when the note fell due and was presented to the Lord for redemption, it was disowned. The law representatives immediately called at Dodd’s house to inform him of the accusation of forgery and advise him that if he wanted to save himself from prosecution and incarceration he was to return all of the money forthwith. The Rev. Dodd explained that he had been obliged to commit the fraud by a debt which had fallen due at a time when he was short of money and he could not meet his obligation. In any case, said Dodd he always intended to return the sum he had borrowed. And indeed, true to his word, he immediately handed a great part of the sum in cash to them , signed a few promissory notes and allowed a charge to be raised on his house belongings for the remaining balance.

He then pleaded forgiveness with the Earl of Chesterfield

Earl of Chesterfield

but to his mortification he found that his noble pupil showed no clemency and later he will even appear in Court to testify against him.

The matter became of public knowledge; the Rev. Dodd was remanded in custody and soon found himself at the centre of a scandal with fatal consequences for him.

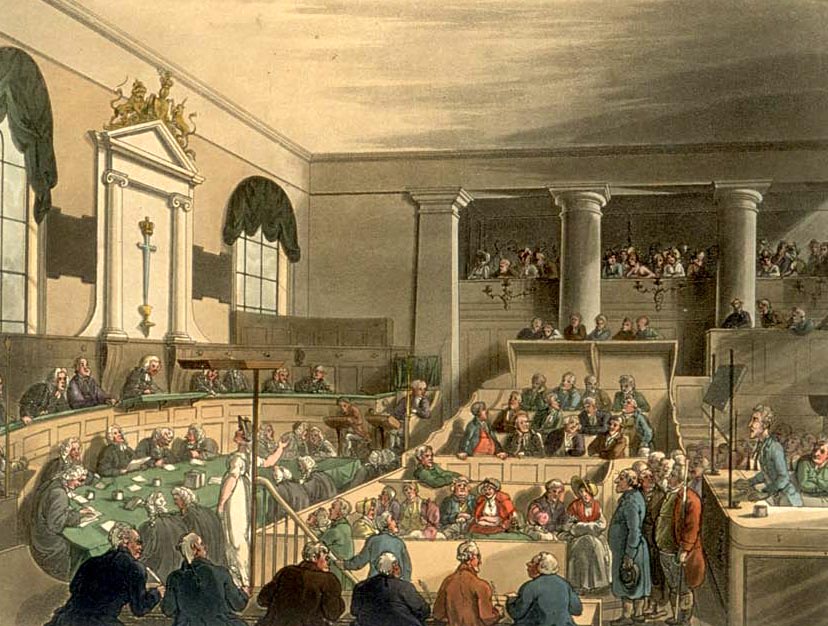

THE TRIAL

On February 19th 1777, Dodd appeared at the Old Bailey.

With no lawyer to defend him, he pleaded for mercy with the Court and delivered a speech from which we have extracted the following:

With no lawyer to defend him, he pleaded for mercy with the Court and delivered a speech from which we have extracted the following:

“My Lords and Gentlemen of the Jury, (…) there is no man in the world who has a deeper sense of the heinous nature of the crime for which I stand indicted, than myself.

(…) I humbly apprehend, though (I am) no lawyer, that the (…) malignancy of a crime – always both in the eyes of the Law and of Religion – consists in the intention.

(But) such intention (to defraud), my Lords and Gentlemen of the jury, has not been sufficiently proven on me (…), for ample restitution has been made.

I leave it to you, my Lords and Gentlemen of the Jury, to consider that if an unhappy man ever deviates from the Law and yet in (a) moment of recollection does all that he can to make full and perfect amends, what (…) can God and man desire further ?”

Dodd then went on to cry out that he had been “perused with excessive cruelty” and “persecuted with a scarcely parallel cruelty” even though reassurances had been given to him after he had made restitution. His death, he said, did not matter to him but it was the loss caused to those he would have left behind that concerned him.

“I have, my Lord, ties which render me desirous even to continue this miserable existence.

I have a wife who for 27 years has lived as an unparalleled example of conjugal attachment and fidelity (…) I have creditors, honest men, who will lose much by my death. (And so) I hope for the sake of justice towards them, that some mercy will be shown to me”.

It was a preposterous defence. The jury returned a guilty verdict and the judge pronounced his sentenced in these words:

“Dr William Dodd, you have been convicted of the offence of publishing a forged and counterfeit bond (…) and you have had an impartial and attentive trial. The jury to whose justice you have appealed have found you guilty and (…) the judges have found no grounds to impeach the justice of that verdict.

(…) your application for mercy therefore must be made elsewhere.

(…) I am now obliged to pronounce the sentence of the law, which is that you, Dr William Dodd, be carried from hence to the place from whence you came, that from thence you are to be carried to the place of execution where you are to be hanged by the neck until you are dead”.

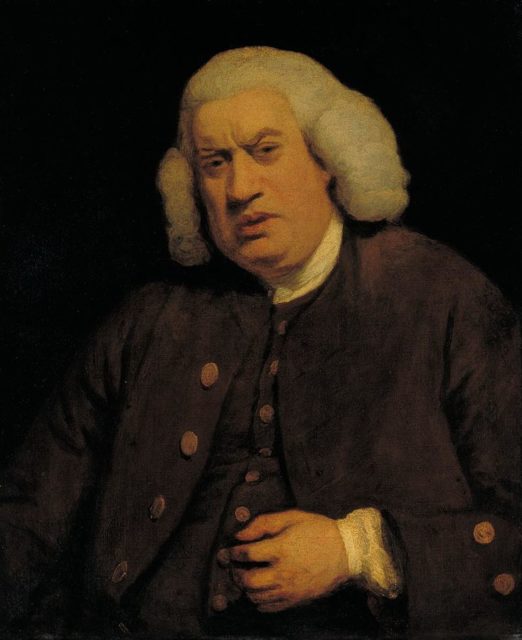

DR SAMUEL JOHNSON INTERCEDES

The XVIII century diarist James Boswell wrote in his diary that on Monday September 15th 1777 he went with his lifetime friend Dr Samuel Johnson  to visit the garden of the school of Ashbourne; a very pretty place on a bank of the river. It was a hot day and they sat on a bench for a little rest, whereupon Johnson – Boswell reports in his diaries – told him of his “humane interference” on behalf of the Rev. Dr Dodd whom he barely knew. Knowing Johnson’s persuasive power of writing Dodd had asked him, through the interception of the late Countess of Harrington, to employ his pen in his favour by writing a letter of supplication to the King so that “(the King) may spare me the ignominy of public death which the public itself is solicitous to waive, and grant me in some distant part of the globe to pass the remainder of my days in penitence an prayer (…)”.

to visit the garden of the school of Ashbourne; a very pretty place on a bank of the river. It was a hot day and they sat on a bench for a little rest, whereupon Johnson – Boswell reports in his diaries – told him of his “humane interference” on behalf of the Rev. Dr Dodd whom he barely knew. Knowing Johnson’s persuasive power of writing Dodd had asked him, through the interception of the late Countess of Harrington, to employ his pen in his favour by writing a letter of supplication to the King so that “(the King) may spare me the ignominy of public death which the public itself is solicitous to waive, and grant me in some distant part of the globe to pass the remainder of my days in penitence an prayer (…)”.

Dr Johnson, who had only been once in the company of the Rev. Dodd many years earlier and never visited him at Newgate prison, wrote these lines for Dodd to use in his letter to the King:

“May I not offend your Majesty that the most miserable of men applies himself to your clemency (…) a clergyman whom your laws and judges have condemned to the horror and ignominy of public execution.

I confess the crime …but humbly hope that sparing the spectacle of a clergyman dragged through the streets to a death of infamy, justice may be satisfied with irrevocable exile, perpetual disgrace and hopeless penury.

My life, Sir, has not been useless to mankind. I have benefited many. (…)Preserve me, Sir, by your prerogative of mercy (…) permit my to hide my guilt in some obscure corner of a foreign country (…) I am, Sir, your Majesty’s, &c. “

In a post scriptum Johnson recommended Dodd never to disclose who the real author of such words was: “Tell nobody” stressed the Doctor and with it he also advised Dodd not to indulge in hope.

Samuel Johnson also wrote many petitions and letters on the Rev. Dodd’s behalf and was the author of the errant Mason’s sermon called “The Convict’s address to his unhappy Brethren” [4] whose lines Dodd read in the Chapel of Newgate Prison as perhaps a last attempt to sway matters in his favour! The sermon suggested in so many words that if one sincerely repents of a crime he has committed , God (and therefore by association, the King ) should pardon him and set him free to go and repent for the rest of his life, rather than be sent to death.

Although Johnson never admitted that such sermon was the product of his mind, when challenged by a friend he answered: “Depend on it, Sir, that when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, he concentrates his mind wonderfully”.

Having lost any hope of a royal pardon, Dodd wrote a final letter to Johnson to thank him for all that he had done for him: (…) as I shall be admitted to the realm of bliss before you, I shall hail your arrival there with transports, and rejoice to the knowledge that you were my comforter, my advocate and my friend! God be ever with you!”

Dr Johnson was moved by such words and wrote back: “may God (…) accept your repentance” and “in requital of those well-intended offices which you so emphatically acknowledge, let me beg you that you make (in your devotions) one petition for my eternal welfare.”

These lines, so full of irony and wit, bring a smile on my face whenever I read them.

At the time, Dr Johnson’s health was deteriorating and he had become particularly scared at the thought of dying. One night Boswell was struck by the expression of horror on Johnson’s face at the mention of the word “death” and of the Rev. Dodd during conversation.  Boswell was expressing his full of admiration for the determination with which Dodd had met his creator a few days earlier. “Dr Dodd seemed to be willing to die and was full of hopes and happiness”, said Boswell. But Johnson retorted that hardly any man dies in public with apparent resolution: “Sir” –said Johnson – “Dr Dodd would have given both his hands and both his legs to have lived because the better a man is, the more afraid is he of death, having a clear view of infinite purity”.

Boswell was expressing his full of admiration for the determination with which Dodd had met his creator a few days earlier. “Dr Dodd seemed to be willing to die and was full of hopes and happiness”, said Boswell. But Johnson retorted that hardly any man dies in public with apparent resolution: “Sir” –said Johnson – “Dr Dodd would have given both his hands and both his legs to have lived because the better a man is, the more afraid is he of death, having a clear view of infinite purity”.

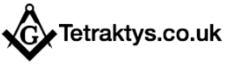

THE EXECUTION

The Rev. Dr. Dodd was allowed to be driven to his place of execution by a private coach and his father is said to have accompanied him on the journey. Every face in the crowd expressed sadness for the fate of that popular preacher who was also a respectful author of books, poems, theological works and newspaper articles and for whom a twenty three pages long petition full of signatures had been presented to the Authorities in the hope that it would spared him from the gallows.

The death-by-hanging technique improved only in the 20th century when mathematical formulas begun to be applied to determine the length of the rope and the height of the drop required to break the person’s neck, quickly. But in the days when such factors – height, weight and neck size of the condemned – where never taken into consideration , the condemned’ s death would have occurred only by a long and inhumane process of strangulation.

The death-by-hanging technique improved only in the 20th century when mathematical formulas begun to be applied to determine the length of the rope and the height of the drop required to break the person’s neck, quickly. But in the days when such factors – height, weight and neck size of the condemned – where never taken into consideration , the condemned’ s death would have occurred only by a long and inhumane process of strangulation.

Often the family members of the executed person would run under the gibbet and pull his or her legs so as to hasten asphyxiation.

However, it is also the case that the shorter the drop was, the highest the chance of the condemned surviving and being revived if freedom from the noose could be secured within a few minutes.

The latter is just what was attempted on Rev. Dodd’s body as it is recorded that no sooner the cart driver had run forward to cause him to hang, that the same driver returned to steady Dodd’s legs, stop his convulsions and cut the rope.

The Rev. Dodd’s family had pre-arranged and paid for the body of Dodd to be transported from the place of execution in Tyburn to a barber-surgeon’s shop near Oxford Street where an attempt would have been made to resurrect Dodd with hot and cold water baths.

But the mobbing crowd which lined and blocked parts of the journey caused such a delay that the short transit of about eight minutes took over two hours.

By the time the coach reached the barber’s shop, any sign of life in Dodd’s body had of course extinguished.

However the myth of this unfortunate Freemason and man of the Church lived on for many more years because the Northampton Mercury edition for Saturday 18 October 1794 , reported that the Reverend Dodd ‘s body had been successfully revived and that he had escaped to France.

CONCLUSION

All Master Masons are sworn to form, metaphorically speaking, a “column of mutual support and defence” when it is necessary to defend a Brother’s honour. But in the case of this reckless clergyman it is clear that Freemasonry wanted to have no part.

The Reverend Dr. Dodd had insulted the integrity of the wife of the King’s Chancellor, had been keeping a lifestyle little akin to that of a man of the cloth and had been gambling and losing money he did not have. Furthermore as a “Macarone” he might, for all we know, have belonged to that crowd of dandified men who were no strange to the rumours of vice and sodomy which was a serious crime at the time.

The Rev. Dodd had claimed to have been the author of many books – almost 50! – of translations and newspaper articles and yet we know for almost certain that he could not himself write a supplication letter to the King but had to ask Samuel Johnson to do so for him.

He had also fully confessed his crime and naively undertaken to defend himself in a Court of Justice. In short, his weaknesses had disgraced him sufficiently to have pushed the boundary of intervention by his Brethren in his “support and defence” well out of reach. The Right Rev. Thomas Newton, Bishop of Bristol in 1777, on hearing of the execution of the Rev. Dodd for the crime of forgery, was reported to have exclaimed: “He has hanged for the least of his crimes”.

As for Philip Stanhope, the 5th Earl of Chesterfield [5], he was no common Brother but a nobleman who descended from a family of Freemasons and was destined , within a few years, to become an important Peer of the Kingdom.

He recognised that the only right thing for him to do was to uphold the Masonic principle that “murder, treason, felony and all other offence against the laws of God and the ordinances of the realm” – perpetrated by a Freemason and confessed to another – “must at all time be most especially excepted” from being kept a secret. And so the Lord chose neither to excuse nor to pardon the Rev. Dodd but by even testifying in Court for the Prosecution, he sealed Dodd’s fate.

In closing, we must not think that the outcome of this story is indicative of a society and of a Masonic Order which were upholders of rule and justice. They were not, particularly in that epoch.

In society – and by reflection in the Craft – then like now, all are equal but some are and will always be “more equal than others”!

By W.Bro. Leonardo Monno Anglisani – NHL 6557 ,Middlesex, England

The author forbids any reproduction or publication of this article, in full or in part, without his explicit authorization.

SOURCES The Masonic Square (UK) “Dr William Dodd Grand Chaplain” by Bernard Williamson “Reverend William Dodd” - article published in the Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon’s website “The sad case of Dr. Dodd” – from “Everybody’s Boswell”

[1] Born in 1729 and executed on 27th June 1777

[2] The Lodge was named St Alban’s Lodge in the year 1771

[3] From “Oscar Wilde prefigured: Queer Fashioning and British Caricature, 1750-1900” by Dominic Janes

[4] A twenty four pages long text that is remarkable for the amount of lexicon used. The Rev. Dodd dedicated it to the Reverend Mr Villette, Ordinary of Newgate Prison

[5] Philip Stanhope (10.11.1755-29.08.1815) became the British Ambassador to Spain (1784-1787) and Master of the Mint (1789-1790), Joint Postmaster General (1790-1791) and Master of the Horse (1798-1804).

- His Majesty’s Servant , David Garrick Esq – Freemason ? - June 7, 2024

- Influencia de la Masonería en Chile - April 29, 2024

- Pomegranate in Freemasonry – its significance - March 11, 2024