For well over a century the larger part of Freemasonry in the French republic has not been recognised as regular by the United Grand Lodge of England, and by most other adherents to what has been described as “the American-English” style of Freemasonry. The reasons for this are largely well-known, and are chiefly connected with the abandoning, in 1870, by The Grand National Orient de France, the oldest and largest masonic group in France, of a requirement to believe in a Supreme Being as a prerequisite for Initiation into the Order. Further problems of recognition have continued to crop up in more recent times, right up to 2007.

Related to this is the fact that whereas our institution has sedulously ensured its apolitical nature over the past three centuries – we can all recollect being adjured in the Charge After Initiation to “refrain from all political and religious discussion” – French Freemasonry has been characterised by a readiness to express, as a body, official lines on all manner of political, social and cultural issues. This preparedness to put their heads above the parapet in such an open way has, I fear, led to a feeling in some quarters that the persecution of such a conspicuous organisation was inevitable under a totalitarian dictatorship, and almost courted.

I hope that the present paper will redress some of that neglect, and I would like to think that it may serve Freemasons of whatever background two useful functions: firstly, it will preserve the memory of the many thousands of French Freemasons who were brutally persecuted during the German occupation of France and secondly it will provide us with a picture of what would have happened had our island been invaded by Nazi Germany, a picture which is an extension of the fate of Freemasonry in the Channel Islands which has previously been described eloquently in this lodge.

Background: the Fall of France

France declared war on Germany on 3rd September 1939, at the same time as Britain, in accordance with the terms of the Franco-Polish Military Alliance of 1921, which, like the Anglo-Polish Alliance, required French support against the invasion of Poland by Germany on 1st September.

There followed some eight months of what is now referred to as the “Phoney War”, (Drole de Guerre or Sitzkrieg) during which neither Britain nor France launched any significant land offensives against German forces.

This ended on 10th May 1940, with the invasion by Germany of the Low Countries, drawing in the British Expeditionary Force which had been stationed on the French side of the border of neutral Belgium since October 1939. Over the next few days, German armour and troops poured into France on two main fronts, supported by the Luftwaffe, and in spite of initial stiff resistance by some French divisions, they easily overwhelmed the less well-equipped and trained French. The B.E.F. retreated to Dunkirk, and was of course evacuated in Operation Dynamo between 27’” May and 4th June.

The French government was in a crisis of indecision: Prime Minister Paul Reynaud wanted the government to flee abroad, to French North Africa, and to continue the war from there, supported by the formidable French Navy.

He was opposed by the Commander in Chief of French forces, General Weygand , and the Deputy Prime Minister Marshall Philippe Petain. Churchill flew to France on 11th June to meet Reynaud, Petain and Weygand; he discussed with them the defence of Paris by guerrilla warfare and house-to-house fighting, not knowing that Weygand had already ordered that Paris, which by now was almost deserted, be surrendered to the Germans. Petain and Weygand, who shared right-wing, anti-republican authoritarian and vehemently anti-communist views, were concerned that if the government went abroad the country would be broken up and easy prey for German and Italian colonisation. They wanted the French forces to retain enough power to repel communist overthrow. When Churchill returned to England that evening, it was clear that France was about to fall. He returned to Tours on 13th June, and Reynaud asked for a release from a previous agreement that he would not seek an armistice with the Germans without Britain’s consent.

, and the Deputy Prime Minister Marshall Philippe Petain. Churchill flew to France on 11th June to meet Reynaud, Petain and Weygand; he discussed with them the defence of Paris by guerrilla warfare and house-to-house fighting, not knowing that Weygand had already ordered that Paris, which by now was almost deserted, be surrendered to the Germans. Petain and Weygand, who shared right-wing, anti-republican authoritarian and vehemently anti-communist views, were concerned that if the government went abroad the country would be broken up and easy prey for German and Italian colonisation. They wanted the French forces to retain enough power to repel communist overthrow. When Churchill returned to England that evening, it was clear that France was about to fall. He returned to Tours on 13th June, and Reynaud asked for a release from a previous agreement that he would not seek an armistice with the Germans without Britain’s consent.

German troops entered Paris unopposed on 14th June. Reynaud was in Bordeaux with the rest of the fleeing government, and resigned as Prime Minister. On 16th June, President Albert Lebrun appointed Marshal Pertain as his successor.

On 22nd June an Armistice, the Second Compiegne Agreement, was signed with Germany. The Northern and Western parts of France, constituting about 60% of the country, were occupied by Germany. The remainder was under the direct French control of a new government based in the town of Vichy. Both the Zone Libre (Vichy) and the Zone Occupee (North and West) were nominally under the control of the Vichy government. One of the conditions of reaching the armistice was that France would not have its territory divided up between Germany and Italy. The demarcation lines existed until the invasion of North Africa by the Allies in Operation Torch on 8th November 1942, when Germany took control of the whole of France.

On 22nd June an Armistice, the Second Compiegne Agreement, was signed with Germany. The Northern and Western parts of France, constituting about 60% of the country, were occupied by Germany. The remainder was under the direct French control of a new government based in the town of Vichy. Both the Zone Libre (Vichy) and the Zone Occupee (North and West) were nominally under the control of the Vichy government. One of the conditions of reaching the armistice was that France would not have its territory divided up between Germany and Italy. The demarcation lines existed until the invasion of North Africa by the Allies in Operation Torch on 8th November 1942, when Germany took control of the whole of France.

On the 10th July the government in Vichy voted Marshal Petain “extraordinary powers” effectively making him President and an absolute ruler. Petain appointed Pierre Laval as his Prime Minister.

The Germans in many ways “left the French to it”. Much of the Vichy administration comprised of men like Petain, who were reactionary, anti-republican, anti-democratic, and vehemently anti-Semitic, and favoured an authoritarian and Draconian regime. Without specific instructions from the Germans, they instituted policies of persecution, internment and deportation of Jews, Gypsies, Protestants, homosexuals and Freemasons.

Persecution of Freemasons

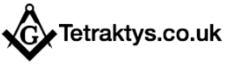

The Third Reich already had a long history of anti-Masonic activity, and this was quickly expoused by the Vichy government. In addition to the belief that Freemason and Jews were involved in plots for world domination, there was also a conviction that lodges were the owners of untold treasures, which would be confiscated by the Reich.

The Vichy regime soon found plenty of support for these ideas: a key figure was Bernard Fay, a minor academic, who was appointed on 6th August 1940 as director of the Bibliotheque Nationale to replace the previous incumbent, Julien Cain, who was removed from the post soon after the occupation as he was Jewish. Fay also began work for the Propaganda Abteilung Frankreich, or Departement de la Propogande en France, which was established in the Majestic Hotel in the Avenue Kleber in Paris, under the direction of Colonel Heinz Schmitdke, a protégé of Goebbels.

The Departement’s function, amongst other things, was to retrain French cultural thought along Nazi lines. Under its auspices was founded the Centre D’action et de Documentation (Centre for Action and Documentation) which was simply an organisation dedicated to the destruction of Freemasonry, its vilification in the eyes of the French public, and the persecution of its members. The centre was originally based at 11 Rue Hubert-Colombier, in Vichy, later moving to the Hotel Mondial. The Centre was run by its director, Henri Coston, a journalist with known far-right sympathies, who was a member of the Partite Populaire de France, a fascist party run by Jacques Doriot.

The Departement’s function, amongst other things, was to retrain French cultural thought along Nazi lines. Under its auspices was founded the Centre D’action et de Documentation (Centre for Action and Documentation) which was simply an organisation dedicated to the destruction of Freemasonry, its vilification in the eyes of the French public, and the persecution of its members. The centre was originally based at 11 Rue Hubert-Colombier, in Vichy, later moving to the Hotel Mondial. The Centre was run by its director, Henri Coston, a journalist with known far-right sympathies, who was a member of the Partite Populaire de France, a fascist party run by Jacques Doriot.

Coston surrounded himself with others of like mind. As well as Bernard Fay, there were Robert Vallery-Radot, Jean Marques-Riviere, Albert Vigneau, Jacques Ploncard d’Assac and William Gueydan de Roussel, who acted as Fay’s secretary. Together the anti-Masonic activists took over the headquarters of the Grand Orient de France in the Rue Cadet in the 9th Arrondissement in Paris and other Masonic sites in both the Occupied and Free Zones, confiscating artefacts and collecting the names of some 60,000 individuals known to be Freemasons. Partly through de RousseI’s contact with Gestapo headquarters in the Avenue Foch, some 1000 Masons were arrested and deported to work camps: over 500 of these were shot. This was associated with a Nazi officer, Lieutenant Ernst Moritz Hesse, who was responsible for much of the Masonic round-up. Many more lost their jobs, as the new anti-Masonic laws promulgated by the Vichy administration equated Jews and Freemasons, and placed the same restrictions on both, as “enemies of the State”.

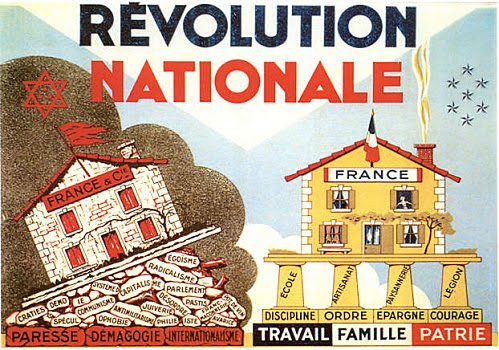

In October and November 1940, Fay and Coston staged an anti-Masonic exhibition at the Petit Palais in what is now, ironically, called the Avenue Winston Churchill. The exhibition purported to demonstrate Masonic rituals and to “expose” world Judeo-Masonic conspiracy. The newly opened Musee des Societes Secretes in the Grand Orient building, with Fay as its director, was also the centre of the Service des Societes Secretes, also under Fay. His determination in persecuting Freemason and seizing their assets was enough to bring him to the attention of the Nazi occupiers, who considered him in March 1941, as a possible candidate for the position of director of the Office Central des Juifs.

In October and November 1940, Fay and Coston staged an anti-Masonic exhibition at the Petit Palais in what is now, ironically, called the Avenue Winston Churchill. The exhibition purported to demonstrate Masonic rituals and to “expose” world Judeo-Masonic conspiracy. The newly opened Musee des Societes Secretes in the Grand Orient building, with Fay as its director, was also the centre of the Service des Societes Secretes, also under Fay. His determination in persecuting Freemason and seizing their assets was enough to bring him to the attention of the Nazi occupiers, who considered him in March 1941, as a possible candidate for the position of director of the Office Central des Juifs.

From 15th October 1941 to June 1944, Coston published from Rue Hubert-Colombier, and later from the Hotel Mondial, a monthly magazine entitled Les Documents Maconniques. Written largely by Coston, Fay (who contributed some 31 articles in 3 years) and about 40 other anti-Masonic activists, it contained an unremitting digest of anti-masonic and anti-Semitic diatribe, designed to prove that the fall of France was the result of having been drawn by world conspirators into a war with Germany which was unnecessary and which was designed specially to bring France to its knees.

The dialectic attempted to show that this had begun as early as the French Revolution in 1789, many of the anti-Masons being counter-revolutionary, anti-Republican and Royalist, as was Petain himself.

In addition to the Documents , Fay also commissioned a feature film,

Forces Occultes, which purported to depict a young French official seduced into Freemasonry and corrupted by it, and eventually realising too late that it was behind the drawing of France into a catastrophic war when it should have made peace with its German neighbours. The film is remarkable for a number of reasons. Firstly, it has to be admitted the effort which had gone into producing it was considerable, especially given the period. Although no one would claim that the acting and direction are of Oscar-winning standards, the production values are comparable with those of other films of the period. Secondly, it is extraordinary that the SS and the Centre D’action et de Documentation were provided with the resources by the government to produce such a film. Under the terms of the Compiegne Armistice, France had to pay millions of Reichmarks to Germany every day, fixed at a ruinous rate, effectively funding the occupation themselves. There were widespread shortages of food, petrol, domestic fuel, and other consumable goods. That the Vichy government could justify the expenditure necessary to make this film under these circumstances, even with some help from the German authorities, testifies to the deep seated and fundamental nature of the furious extremely prejudiced views held by those concerned; not only at the level of the technocrats and hack writers like Fay and Coston, but right up to the level of Petain and Laval. The basis of this was obviously the underlying ideology of the Nazi occupiers – in 1942 Hitler had authorised Alfred Rosenberg to wage an “intellectual war” against the Jews and Freemasons, and guaranteed him the support of the High Command of the Wehrmacht in achieving their mission to collect data and artefacts in pursuit of this aim. It seems possible then, that the film is part of a strategy not conceived by the French journalists, but from much higher up the occupation ladder.

Forces Occultes, which purported to depict a young French official seduced into Freemasonry and corrupted by it, and eventually realising too late that it was behind the drawing of France into a catastrophic war when it should have made peace with its German neighbours. The film is remarkable for a number of reasons. Firstly, it has to be admitted the effort which had gone into producing it was considerable, especially given the period. Although no one would claim that the acting and direction are of Oscar-winning standards, the production values are comparable with those of other films of the period. Secondly, it is extraordinary that the SS and the Centre D’action et de Documentation were provided with the resources by the government to produce such a film. Under the terms of the Compiegne Armistice, France had to pay millions of Reichmarks to Germany every day, fixed at a ruinous rate, effectively funding the occupation themselves. There were widespread shortages of food, petrol, domestic fuel, and other consumable goods. That the Vichy government could justify the expenditure necessary to make this film under these circumstances, even with some help from the German authorities, testifies to the deep seated and fundamental nature of the furious extremely prejudiced views held by those concerned; not only at the level of the technocrats and hack writers like Fay and Coston, but right up to the level of Petain and Laval. The basis of this was obviously the underlying ideology of the Nazi occupiers – in 1942 Hitler had authorised Alfred Rosenberg to wage an “intellectual war” against the Jews and Freemasons, and guaranteed him the support of the High Command of the Wehrmacht in achieving their mission to collect data and artefacts in pursuit of this aim. It seems possible then, that the film is part of a strategy not conceived by the French journalists, but from much higher up the occupation ladder.

Epilogue

Following the Allied invasion of Normandy, the Vichy regime was dismantled with the liberation of France, the high point of which was the liberation of Paris on 25th August 1944. The Vichy government for the most part fled to Germany, and the final blow came on 23rd October 1944 when the US, Britain, and the USSR, recognised the Gouvernement Provisionelle de la Republique de France as the legitimate government.

Almost immediately reprisals began against those who had collaborated with the occupying forces, and there were numerous summary executions. The end of the war saw widespread trials (epurations legales) and harsh sentences meted out to those who were seen as having joined the Nazis.

Petain escaped the death penalty by dint of his age – he was 85 at the end of the war. Laval was not so fortunate, and was shot as a traitor after a widely publicised trial on 4th October 1945.

Those directly involved in the persecution of Freemasons suffered varying fates.

Bernard Fay was arrested in his office at the Bibliotheque Nationale on 19th August 1944. He was tried as a collaborator and sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labour, confiscation of his property and Indignite Nationale, which effectively meant being stripped of most of the benefits of French citizenship. He escaped from prison while in hospital in 1951, and settled in Fribourg in Switzerland. He was pardoned in 1959, and died in 1978.

Henri Coston fled to Germany and then to Prague, finally being arrested in Austria, tried as a collaborator and sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labour. He received a pardon on medical grounds in 1951. He died in Caen in Normandy in 2001 at the age of 90. He continued to write anti-Masonic and anti-Semitic articles for the rest of his life.

Jean Marques-Riviere, who wrote the screenplay for Forces Occultes, fled to Germany with the fugitive Vichy officials. He was tried and sentenced to death in his absence. He travelled after the war between Asia and Franco’s Fascist Spain, was pardoned under an amnesty and died in Lyon in 2000.

The director of the film Forces Occultes, Jean Mamy (a.k.a. Paul Riche) was tried under the process depuration and at dawn on 29th March 1949, he had the distinction of being the last collaborator executed by firing squad.

Author: W.Bro. Seth Belson, LGR .

Article released by courtesy of the Temple of Athene Lodge of Research N.9541 – Transaction volume 21/September 2015. Copyright protected.

- His Majesty’s Servant , David Garrick Esq – Freemason ? - June 7, 2024

- Influencia de la Masonería en Chile - April 29, 2024

- Pomegranate in Freemasonry – its significance - March 11, 2024