The life of Thomas Dunckerley was one of a major importance to the Craft. No other 18th century English Freemason occupied so many distinguished offices as he did. His story is an engaging reading that will also fill your mind with questions. Thomas ’s motto was “Fato non Merito” [1] and nothing summarises his life better than those words.

Thomas Dunckerley was born in London on 23 October 1724, the child of Mary Bolness, wife of Adam Dunckerley who became a porter at Somerset House. Although Mary’s husband deserted her when he found out she was carrying an illegitimate child, Mary was able to support – for reasons that will be disclosed to you later – Thomas’s private education at boarding school. That experience, however, proved an unhappy one for the child who, at the age of ten, decided to run away from the institution and never return. His grandmother took him under her mantle and cared for him until, still a child, he joined the Royal Navy’s “Boy Service“ as a “Powder monkey or “Nipper‟.

In the 18th century there were very many adolescent boys serving aboard British ships. Some of them were orphans or foundlings, others were just delinquent and troublesome juveniles.  Although the Navy did not provide an apprenticeship leading up to an independent trade, it gave long-term employment to those who were fit and healthy. The Navy recruited from a wide spectrum of the society and even practiced impressment, a custom of forcing any men of age 18 and upwards to serve the Nation for a specific time and in situations of war, even against their will. Many such individuals and children stayed on and progressed through the ranks , reaching captaincy and receiving commissions . A few even ended their service as Admirals.

Although the Navy did not provide an apprenticeship leading up to an independent trade, it gave long-term employment to those who were fit and healthy. The Navy recruited from a wide spectrum of the society and even practiced impressment, a custom of forcing any men of age 18 and upwards to serve the Nation for a specific time and in situations of war, even against their will. Many such individuals and children stayed on and progressed through the ranks , reaching captaincy and receiving commissions . A few even ended their service as Admirals.

Geometry was a science that all ship gunners had to learn as it was used to calculate the correct inclination of a cannon in relation to the target and the speed of the ships in combat. By distinguishing himself in that task, Thomas became “Master Gunner” at only 24 years of age. However, he remained in that rank until he retired twenty-six years later. During his time in the Navy Thomas travelled extensively, taught Maths to his ship’s crew, engaged in many sea skirmishes and took part to the siege of Quebec [2] during the Seven Years’ war.

Throughout those years at sea, Thomas received much commendation and tokens of friendship from all the Officers under whom he served. However, merit and seniority were not the only elements required to secure a career; the influence of friends in prominent places was also a crucial factor and sadly Thomas had none.

THE ROYAL SEDUCTION STORY

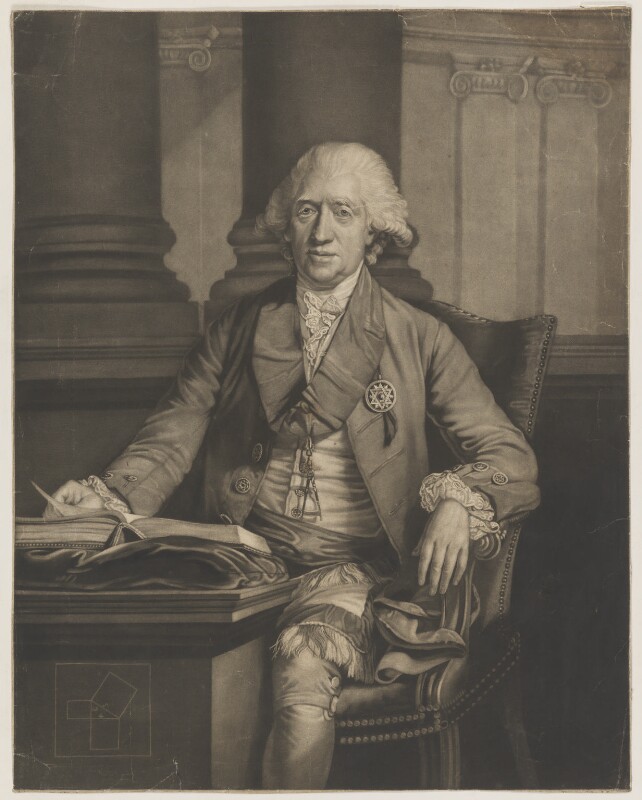

In 1760, Mary Dunckerley had passed away and Thomas, on his return to London from Quebec, was to discover a story that put him in a new and extraordinary light. On her deathbed, Mary had confided to her neighbour that she became pregnant with Thomas as the result of a brief relationship with the Prince of Wales, the future King George II of England (in the portrait below).

Mary Dunckerley was the daughter of a physician and she lived and worked in the household of the Right Hon. Robert Walpole – a subsequent Prime Minister of England – at Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Mary had gained a solid education, and it is realistic to assume that she was Lady Walpole’s personal assistant rather than one of her servants. The philandering German speaking Prince of Wales, had become fond of the Walpoles [3] and being a recurrent visitor to Houghton Hall, on one such visit he seduced Mary. Lady Walpole did not fail to notice what was taking place under her roof and swiftly moved to bring the embarrassing situation to an end. She schemed an expedient whereby she would find a husband for Mary and then despatched the married couple to live and work hundreds of miles away from Houghton Hall.

Lady Mary Walpole confided in her friend the Duke of Devonshire [4] whom recommended that the future consort of Mary should be an anonymous Adam Dunckerley. He summoned the young man at his Chatsworth House and kept him there until the terms of the arranged marriage were accepted. Clearly either Adam or Mary, if not both, must have had a few reservations. Perhaps their different social status and education played a part in the dithering. After the wedding the couple moved to London where Adam, in exchange for free accommodation, took up the post of porter at Somerset House. The trade of a porter in the early 18th century London entailed carrying wealthy and important individuals in sedan chairs – which provided protection from mud, snow, rain or sun – back and forth through the unpaved streets of London. Porters also loaded and offloaded luggage from horse carriages, cargo from river boats and so on. Theirs was a demanding job, but one that greatly contributed to the growth of the economy in the Capital.

Somerset House (in the picture above) is a beautiful palace just off the Strand, famous worldwide for being immortalised in a painting by Canaletto. The architect Christopher Wren, whom some believe was a Freemason, refurbished it magnificently in 1685. A few decades later , however, the structure fell into disrepair and ceased offering adequate accommodation to foreign Royals, Aristocrats and diplomats. Instead, it provided simple lodgings in exchange for grace and favours.

When in November 1723 Adam Dunckerley left Somerset House to do some errands for the Duke of Derbyshire – he was absent for five months, until May 1724! – he left Mary with much idle time to occupy herself. With Christmas approaching, she set on visiting some of her friends and acquaintances. One of those cronies was Lady Margaret Ranelagh (1672-1728) who lived at 83-84 Pall Mall, London.

On her deathbed Mary confided to Ann Pinkney – the wife of another porter at Somerset House –that one day she went into the parlour of her host’s house and found the Prince of Wales whom she “had too well known” before her unhappy marriage. “At his request and for I could deny him nothing” – said Mary – “I stayed at the house for several more days during which time the Prince made five visits to me” and in one encounter made her pregnant! For the cuckold Adam Dunckerley, this proved too much to bear. He opted out of Mary’s life and disappeared from the records.

The events that followed seem to endorse the argument that Thomas truthfully had a royal “connection”. Proof of it is that the expecting Mary, whom under different circumstances would have been left to her destiny, was instead surrounded and tended for by people of status. The Royal Midwife Mrs Sydney Kennion, for example, assisted the child’s birth with the doctor to the Prince of Wales and to the Walpoles – Dr Richard Meade (1673-1754) [5] – in attendance.

Indeed after Thomas’s birth, the Prince of Wales gifted Mary with fifty pounds; enough money to buy a house in those times. Dunckerley recounts: “This information” – the affair with the Prince of Wales – “gave me great surprise and much uneasiness; and as I was obliged to return immediately to my duty on board the Vanguard, I made it known to no person at that time other than Captain Swanton. We were then bound a second time to Quebec, and Captain Swanton promised that on our return he would try to have me introduced to the King, and that he would give me a character reference; but when we came back to England the King (George II) was dead.”

Thomas’ grandmother had been a nurse to Sir Edward Walpole – son of Sir Robert Walpole, a Freemason – and Dunckerley had been hoping in vain that such a connection would have helped him rise in the Navy‘s ranks. But now – it was the year 1760 – Thomas realised that in the light of his mother’s revelations, he could play the ace card of claiming to be a royal bastard and obtain “employment in any department that is adequate to my (…) abilities and which would not depress me beneath the character of a Gentleman”.

By the end of 1763, the year he had retired from the Navy, Thomas had accumulated debts of £150, a sizeable amount of money that he had no hope on earth of repaying in his life. He was drawing a very good pension from the Navy but he was spending it all on medical bills for his sick daughter and his son [8] who needed to be repeatedly bailed out from his gambling liabilities. With the certainty of ending his days in the debtors’ prison, Thomas made a runner.

In 1764 he signed on as a crew member of the HMS Guadeloupe and sailed away to avoid arrest and imprisonment. On board with him was Lord William Gordon, a fellow Freemason who kept good guard on him. Having become ill with the scurvy, Thomas disembarked at Marseilles and underwent treatment at the home of none other than England’s ambassador in town. When he was restored to a good health, Thomas travelled to Paris to rejoin Lord Gordon who gave him £200.00 and dispatched him back to England to clear all his liabilities.

But money never changes hands without good reason!

Only after the death of Thomas’s alleged royal parent in 1766, Thomas’s claim was brought to the attention of the King. The newly crowned [6] George III (in the portrait above) was said to have been very impressed at the number of intimate information in Mary’s deathbed confession. He made enquires into Thomas Dunckerley’s character and being satisfied, he assigned him an annuity of £100 [7] and gave him the use of private apartments at Hampton Court Palace. He also allowed Dunckerley to bear a Coat of Arms that showed the motto “Fato non Merito” and to sign himself as “FitzGeorge” (son of George).

At the age of forty-six Thomas had at last achieved the prestige and economic security he had longed for.

MASONIC CAREER AND WORK

In contrast to his experience in the Navy, Dunckerley’s Masonic career proved glistening. Thomas was initiated into Freemasonry in 1757 and believed to have gone through the three degrees at the “Lodge of the Three Tuns N.31”, one of the Navy Lodges of Portsmouth which met at the pub with the same name. To substantiate that assumption is the fact that he ended his speech – called “The Light and Truth of Freemasonry Explained “ and delivered before the Lodges of Plymouth in 1757 – with words of apology for having boldly written about the subject whilst still very new to Freemasonry. Two years later he reaped his strong enthusiasm for the Craft by becoming the Grand Master of two Plymouth Lodges.

In 1767, Dunckerley received the appointment to Prov. Grand Master of Hampshire and founded several naval Lodges in the County. That first Provincial rank appointment in Freemasonry was a token of true esteem by the Grand Lodge of England – particularly by its Royal Patrons the Prince of Wales (Grand Master of the Order),the Duke of Clarence (Patron of the Holy Royal Arch) and the Prince Edward (Patron of the Masonic Knights Templar Order).

Dunckerley also became the Pro Grand Master for the Masonic Provinces of Bristol, Dorset, Essex, Gloucester, Hereford, Somerset, Southampton & the Isle of Wight. He was also the Grand Superintendent for Kent, Nottingham, Surrey, Suffolk, Sussex and Warwick and the most eminent Grand Master of The Knights of Rose Crucis, Templar, Kadosh and he received the appointment to Past Senior Grand Warden.

However, of far more importance in the Craft was the office that Dunckerley occupied as an instructor of Masonic Lodges and a reformer of Freemasonry. The Grand Lodge of England had in fact authorised him to revise the existing ritual which resulted in Thomas’s removal of part of the third degree ritual and assigning it to the Royal Arch instead. In September 1769, Dunckerley introduced the Mark Mason Degree. Nobody is certain of where he got the idea, but we know that he conferred it for the first time to the Brethren of the Portsmouth Royal Arch Chapter of Friendship No 257. It is also interesting to note that initially there was a “Mark Man” Degree given to Fellow Crafts and a “Mark Master” Degree conferred on Master Masons.

About a hundred years later, the Grand Lodge of England backed off from its initial recognition of Mark Masonry and the Mark could no longer be worked in a Craft Lodge. The Grand Lodge of Mark Master Masons was hence constituted, turning Mark Masonry into a separate and independent Masonic body.

Dunckerley also introduced new Masonic symbols such as the ‘Parallel Lines’ – which represent the two Saint John – and ‘Jacob’s Ladder’. He wrote Masonic songs and hymns, many well-written letters and presented many Lectures.

HIS LATE LIFE

Thomas married young in life and to a much older woman; but the couple lived happily together and even had four children. When Thomas laid the foundation stone of a new Church at Southampton in 1792, he said that “if the structured had been finished by the time he had completed fifty years in wedlock, he should think himself justified in following the practice of some Nations he had travelled in, viz., that of keeping a jubilee year” and being remarried in that Church!

Thomas Dunckerley was a very generous Brother and he continued to give frequent Masonic and social events even when he lived at Hampton Court. He attended public meetings and festivals of the Craft and helped the poor fellows whenever he could. But such benevolence and the regular expenses he incurred for attending all the events of his many Provinces, were costly and caused Dunckerley to effectively lead a poor life.

Dunckerley died in Portsmouth at 71 years of age, in 1795. He had expressed a wish of being buried in the Templars’s Church, London, but was instead laid to rest in St Mary’s Parish Church (shown in the photo above) , Portsea, Portsmouth, in an unmarked grave. An arrangement that speaks volumes!

CONCLUSIONS

Thomas did not show any desire for a classical education and run away from college when he was 10 years old. The excellent proficiency in Maths that he showed later in life, does not compensate for an intellectual education that was never installed onto him. He served in the Navy for twenty-six years – a third of his lifetime! – yet he rose no higher than Master Gunner. He also fell into debt and dishonorably fled the Country. He regained his integrity and avoided imprisonment only thanks to a substantial financial donation – but I suspect we should call it a “lifetime loan” or a bounty – from a Brother Freemason if not from the Grand Lodge of England itself!

How do we otherwise explain that a person with such a background and limited education progressed so significantly in the Craft’s hierarchy, composed Masonic songs, delivered eminent lectures, inspected [9] revised and reformed Freemasonry and even introduced the new Order of Mark Masonry. And he did all that just on his own merit? Why was his body not laid to rest with the reverence and respect that royal blood require?

Susan Sommers is a historian and a recent biographer of Dunckerley, in her article published in the Masonic magazine “The Square” [10] inspirationally states that the 18th century, with its Enlightenment, military wars and civil unrest, was a time of rapid changes which provided the perfect conditions for some men to leave their inglorious, murky or boring past behind and reinvent themselves.

I feel this might be just what Dunckerley did.

Back home and into a civilian life after twenty-six years spent at sea, Thomas stared at financial ruin. What saved him were his human qualities. He was an intelligent, articulate, affable, caring, generous and gregarious individual who got on with everybody. But above all he was a Freemason with a canny physical resemblance to King George II, and with a captivating story that took him out of an anonymous life and gave him the status of a gentleman.

Having escaped incarceration, Thomas very determinedly dedicated the later part of his existence, to the service and glory of Freemasonry. He took on endless work and responsibilities, he entertained, revised, developed and changed all things Masonic.

As the illegitimate child of an English Monarch and a person gifted with noble looks and deportment, Thomas Dunckerley fitted perfectly the profile of a faithful agent for the mysterious and political designs of the 18th century English Freemasonry.And no matter what status he attained later in life, I believe his true worthiness remains shrouded by a thick veil of fabrication.

The author forbids any reproduction or publication of this article, in full or in part, without his explicit authorisation.

[1] It means “by fate not by merit”

[2] It saw the British snatching the Province of Quebec in Canada from the French in 1759

[3] In his role of King , George II relied more and more on the political dexterity of Lord Walpole to govern his realm

[4] William Cavendish, the IV Duke of Devonshire (1720-1764). Duke of Devonshire was just the name of the Title. The Cavendishes were not the Duke of the County of Devon.

[5] Member of the Royal Society of Physician and a Freemason

[6] King George III, grandson of George II

[7] Later increased to 800 pounds.

[8] He was reported to have died in a cellar in St Giles’s prison

[9] In 1760 he received a commission “to inspect the Craft wheresoever he might go”

[10] Thomas Dunckerley – A Masonic hero and/or imposter ? “The Square” – Sept 2013

SOURCES "History of the Mark Degree" by the E. Lancashire Prov. Grand Lodge “Thomas Dunckerley and English Freemasonry” by Susan Mitchell Sommers “The late Brother Thomas Dunckerley” – The Freemasons’ Quarterly Review, March 1842 “Who was Thomas Dunckerley” by WBro. Bro Ken White, Lodge Gosforth, August 1999 “WBro. Dunckerley” – by Edgar W Fentum

- MUSIC AND THE CRAFT – LUIGI BORGHI , A FREEMASON OF THE NINE MUSES LODGE - October 31, 2022

- SPILSBURY – THE FREEMASON FATHER OF FORENSIC SCIENCE - April 18, 2022

- THE MASONIC GLOVES - March 21, 2022