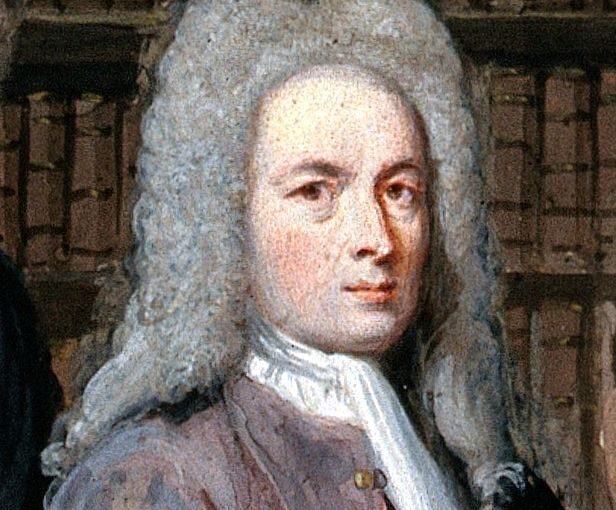

One individual whose reputation lies far from that of the archetypal Huguenot is John Jean Misaubin (1673-1734). It has been estimated that there were some 470 Huguenot refugee who practised the profession of medicine in England, from the beginning of the Reformation until the Huguenots ceased to seek refuge under the reign of George III. Dr John Misaubin was a fashionable ‘quack’ known to posterity thanks largely to the famous image of him by William Hogarth (1697-1764). He has been identified since contemporary times as ‘the thinner of the two doctors in Plate V of ‘A Harlot’s Progress’ published in 1732‘.

Here they are arguing the merits of their respective pills and potions whilst their patient Moll Hackabout, the Harlot, is dying of venereal disease, the reward of their calling.

Unsurprisingly, in the light of Hogarth’s striking and damning portrayal of medical incompetence, veniality and lack of humanity, all succeeding commentators over the years have repeated a pejorative refrain and called Misaubin a “notorious quack”.

Misabubin has a presence in another of Hogarth’s great modern moral subjects’ series, his ‘Marriage a la mode’ of 1743-45.

The meaning of this scene, the third in the series, has always been particularly obscure. The impoverished Count with his young girl friend is visiting a quack who has been said to be Misaubin with his ‘Irish wife’. But not only the image is not a physical representation of Misaubin, his wife Martha (Marthe) Angibaud, was too a French Huguenot. Hogarth’s reference to Misaubin lies in the setting, thought by some commentators to represent Misaubin’s museum at 96, St Martin’s Lane. Here are shown two machines; one for pulling corks and the other for reducing dislocated shoulders! The open folio on the machines reads: ‘Explication de deux machines superbes l’un pour remettre l’épaules l’autre pour servir de tire bouchon inventés par Mons de la Pillule… — vues at approuvées par l’academie des Sciences a Paris’. The other specific reference to Misaubin is the dummy with the long wig in the cabinet indicated by the Count’s cane. Misaubin lived at this address only from 1732 until his death there in 1734.

ln 1719 the artist Antoine Watteau (1684—1721), dying of consumption, visited London and consulted Dr. Richard Mead (1673—1754) a great collector of works of art as well as a world famous physician.

Watteau probably came across Misaubin in the large French community around St. Martin’s Lane, and appears to have made a sketch of him on a paper napkin – probably in Slaughter’s coffee house.”

The print shows Misaubin, in tall and long-wig amidst black crepe, bones, graves and with his cry Prenez des pilules, prenez des pilules !

Misaubin also gained immortality at the hands of the author and reforming magistrate Henry Fielding (1707-54), who was a friend of Hogarth. In Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones, Misaubin’s French accent, self-importance, and an association with death are recalled. In Book Five, Misaubin is quoted as saying: ‘Bygar, me believe the pation take me for the undertaker for they never send for me til de physician have kill dem‘.

Elsewhere in Tom Jones, Fielding writes ‘the learned Dr Misaubin used to say that the post address for him was ‘To Doctor Misaubin, in the world‘, intimating that there were few people in it to whom his great reputation was not known.

Fielding, no doubt also in ironic vein, dedicates his play The Mock Doctor (1732) to the contemporary Misaubin. Fielding refers to that ‘little pill which has rendered you so great a blessing to mankind…the opposite to Pandora’s box‘.

Dr Arbuthnot (1667-1736) is famous for his invention of the John Bull character and for his association with Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and John Gay. He attended Queen Anne in her final lllness.

Misaubin was, dispite all the above, a remarkably well qualified doctor for the times, a fact that even Ronald Paulson, the distinguished Hogarth scholar, does not appear to have known. Paulson refers to the Frenchman as ‘the French empiric‘, that is, an academically unqualified practitioner, he was not. In a previous biographical article the author also betrays an ignorance of Misaubin’s professional qualifications.

The Table below shows some biographical details of Misaubin in the records of the Huguenot Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

- 1673 Born at Mussidan, in the Dordogne

- 1687 MD Cahors

- 1697 In Canterbury

- 1701 Reaffirmed Protestant faith at Threadneedle Street Church with his father

- 1707 Naturalized

- 1709 Married Marthe Angibaud at the French Church of Hungerford Market-

- 1719 Licentiate of the College of Physicians

- 1734 Died at 96 St Martins Lane on 20 April

There must however be doubt about the accuracy of these dates in view of the MD degree, gained apparently at the age of 14. In 1709, the year in which he married Martha (Marthe) Angibaud as noted above, he was living in Berwick Street, Soho. Martha’s father Charles Angibaud, was apothecary to Louis XIV in 1678 but left France with his family just before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. He became Master of the Society of Apothecaries in London 1728 and died in 1731.

Between the years 1706 and 1722 the records show that Misaubin was a witness at two weddings and godfather on two occasions. Misaubin is noted in the French Hospital records as paying 50 shillings a quarter to the hospital for the part keep of an 85 years old female admitted to have been a well-integrated member of the Huguenot community.

In a painting in the Wellcome Collection we see a portrait of Misaubin with his wife Martha (Marthe), his father James (Jaques) who was a clergyman and preached at the French Church in Spitalfields, and his son Edmund, who attended Clare College Cambridge and was murdered in 1740 at the age of 23 whilst returning from Marylebone Gardens.

Misaubin passed the three parts of the College of Physicians examination in physiology, pathology and therapeutics apparently at the first attempt in 1719.

At the Comitia on 25 June 1719, he was admitted Licentiate. The Fellowship of the College was then restricted to graduates of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. However the Licence provided the privilege of being able to practise in, and within seven miles of, the City of London. ln 1708 the College had 67 Fellows and 39 Licentiates. There were fewer in both categories in 1746. In view of the uncontrolled nature of medical practice at the time, the fees charged and the wealth of the physicians probably reflect as much the prestige of the College as the scarcity value of membership of this particular closed shop.

Many commentators allude to the fact that Misaubin made a good deal of money from his practice and pills. The painting by Andien de Clermont that decorated the staircase of his home at 96, St Martin’s Lane, is said to have cost 500 guineas, a colossal sum in those days. One of Andien de Clerrnont’s patrons was Lord Baltimore, who was one of the three nobles asked to ‘supervise’ the execution of Misaubin’s will.

There are no records of anything Misaubin may have written apart from his will, which was made shortly before his death on 20 April 1734. This, however, is a very revealing document. It tells us a good deal about Misaubin’s relations with his wife and family, his personality, and his place in society.

To his wife Martha, for whom he says he had made previous provision, Misaubin left the proverbial one shilling and his best French bible. He left the residue to his son Edmund and says that if Edmun dies before the age of 21 unmarried, Martha and the Angibaud family are not to benefit but the estate is to go to the ‘French Hospital near Hoxton commonly called the Providence. He wanted his ‘Nostrums and Recipes for the cure of distemper and maladies’ to be published for the use and for the benefit of the public ‘since I have always preferred the publik before a private interest’. The antipathy between physicians and apothecaries, a prominent feature of medical practice at the time and even more so in the late 17th century, was certainly reflected in the Misaubin/Angibaud family.

Misaubin made Edmund, then still a minor, the sole executor but entreated the Dukes of Richmond and of Montagu, and the Lord Baltimore, to supervise the execution of the will.

MISAUBIN THE FREEMASON

John Montagu, the second Duke of Montagu (?1688-1749), was a popular courtier, a son-in-law of John and Sarah Churchill – the first Duke and Duchess of Marlborough – and became in 1721 the first noble Grand Master of the Lodge. The lavish London seat, Montagu House, was re-built and serviced by his father Ralph Montagu in the French style, and became the site of the British Museum. Montagu’s good friend, Charles Lennox, second Duke of Richmond (1701-1750), was a grandson of King Charles II and an important figure in the early history of Grand Lodge and of cricket. He was Master of the Horn Lodge for many years, including the year 1730 when Misaubin was initiated.

It is of interest that both Montagu and Richmond shared with Misaubin the distinction of holding medical degrees, although we can be certain neither plied the trade. Following his honorary MD degree from Cambridge earlier that year, Montagu was made an honorary Fellow of the College of Physicians in 1717 ‘at his own request’, setting something of a precedent. Richmond was elected fellow of the College in 1728, in which year he also became MD Cantab. Charles Calvert, fifth Lord Baltimore (1699-1751) was also a Freemason, initiated at a special lodge established by Montagu and Richmond for this purpose. The Calvert family were the proprietors of the colony of Maryland and Charles was a patron of Clermont who had painted Misaubin’s staircase. It seems probable that Misaubin became known to the noble trio through free-masonry but we cannot exclude a relationship encompassing Misaubin’s professional activities.

The London Evening Post of 17 March 1730 informed its readers that on Monday night last at the Horn Lodge in Palace-Yard, Westminster (whereof his grace the Duke of Richmond is Master), there was a numerous Appearance of Persons of Distinction: at which Time the Marquis of Beaumont, eldest Son and Heir-Apparent to his Grace the Duke of Roxburghe; Earl Kerr of Waltefield, a peer of Great Britain; Sir Francis Henry Drake bart, the Marquis De Quesne; Thomas Powell, of Nanteos, Esq; the Chevalier Ramsey; and Dr Misaubin were admitted Members of the ancient Society of Free and accepted masons.’

Misaubin newly initiated brother, the loyal jacobite Andrew Michael (known as ‘Chevalier’) Ramsay came to occupy an interesting place in the history and development of Freemasonry, notably in relation to the higher degrees’.

The Horn Lodge initially met at the Rummer and Grapes Tavern, in Channel Row, Westminster, and was one of the four lodges which formed the Grand Lodge in 1717 and thus established English freemasonry. It is the direct ancestor of today’s Royal Somerset House and Inverness Lodge Number IV. The Horn Lodge had the most socially distinguished membership of the early lodges. In 1723 the 71 members included two Dukes, seven other peers, four baronets or knights and at least ten members of Parliament. The Duke of Richmond was Master from 1723—1738 and both Montagu and Baltimore were members. The lodge’s financial contribution to charity recorded in the early Quarterly Communications reflects the wealth of the members in relation to other lodges. Thus Misaubin was initiated into the socially and financially leading lodge of the day.

In his short Masonic career Misaubin is recorded in June 1731 as present at the consecration of a new lodge in Highgate and as being Master of the Swan lodge meeting in Hampstead. He was in the company of distinguished brethren from the Horn lodge, including the Huguenot.

Dr John-Theophilus Desaguliers, a polymath natural philosopher and supporter of Isaac Newton and a major figure in the early history of Freemasonry.

Misaubin was junior Grand Warden pro tempore, an exalted office, albeit for the one meeting, at the Quarterly Communication of Grand Lodge held at the Devil Tavern within Temple Bar on 2 March 1732. There were again a number of Misaubin’s distinguished Horn Lodge brethren present, including the Duke of Richmond and Desaguiliers. The matters recorded at their Quarterly Communication included the decision that each of the 12 Stewards of Grand Lodge (who had to be wealthy enough to afford to pick up the tab if ticket sales did not cover the cost) would tender the name of his successor for the forthcoming annual feast. There is no record of who chose whom. However the twelfth name on the list for the feast held on April 19, 1732 was one Solomon Mendez (or Medes) and the twelfth name on the list for the stewards for 1733 was none other than ‘Dr Mizaubin’. It seems possible that Mendez, a Jew of Portuguese origin, named as his successor another fugitive from religious persecution. William Hogarth, a freemason since 1725, was twelfth on the list of stewards for 1735. Could Misaubin and Hogarth have had a mutual friend in the person of the twelfth name on the list of Stewards for 1734, one Henry Hutchinson.

William Hogarth’s ‘A Performance of the Indian Emperor, or The Conquest of Mexico‘ (1732-1735) is said to be Hogarth’s greatest conversation piece. It is of particular interest in showing the presence, inter alia, of the Duke of Richmond, the Duke of Montague and Dr Desaguliers.

The painting shows a scene from ‘The Indian Emperor’, a dramatization by John Dryden of the conquest of Mexico, being performed in the house of John Conduitt who succeeded Sir Isaac Newton (his wife Catherine Barton’s uncle) on Newton’s death as Master of the Mint in 1727. The Conduitts are shown in the portraits, and the presence of Newton is indicated by the bust by Louis-Francois Roubiliac (1702-1762) which occupies a central position in the composition. Hogarth is thought to be alluding to the nobility of intellectual genius as superior to that of mere title and rank.

In addition to portraying two of those leading members of the nobility who were asked to supervise Misaubin’s will, ‘The Indian Emperor’ provides a further important connection with Misaubin in the person of Thomas Hill (?-1758) who was a close friend of the Conduitt, an early tutor and member of the Duke of Richmond’s household, a Fellow of the Royal Society and later Secretary of the Board of Trade.

Thomas Hill writes to the Duke of Richmond on at least two occasions of spending time with Misaubin. In February 1733 Hill writes:

‘I dined with Mizzy the other day, who really gave me clean linen and a very good dinner. I stayed with him until 5 and heard very attentively the usual nonsense, larded with a thousand ‘pardieus’. That very night he got drunk with Sir David who came for some pills and before the third bottle and the Doctor both were finished, he told him in the fullness of his heart ‘Pardieu, ce Mons. Hill est un grand genie. He is a wit’. Had this come from any man living, I had concealed it from yr Grace. But Mizzy is one whose eulogium though it concerns oneself, one may venture to repeat without the imputation of vanity’

There is other evidence of the hospitality and drinking which Misaubin extended to his patients such as Sir David. Fielding writes of ‘that generous elegance with which You treat your friends and Patients insomuch that the latter are often Gainers by their Distempers and drink you out more in Wine, than they pay you for Physic.’

That Misaubin drank a lot was thus clearly well known. I have suggested, as noted above, that Hogarth had this in mind when he includes a machine for pulling corks invented by M de la Pillule in the third picture of the ‘Marriage la Mode’ series, set in the quack’s museum. The features of Misaubin’s condition that Thomas Hill describes (notably his swollen ankles and ‘rainbow’ appearance) are very suggestive of advanced cirrhosis of the liver.

The distinction between quacks and regular physicians was by no means clear cut, either in the public perception or in the reality of everyday practice in the 18th century. There was energetic entrepreneurship which, long before evidence-based discourse, consisted largerly of talking down your competitors’ medicines and talking up your own.

The literate lay-public were often well informed about medical practices and exposed to energetic advertising, thanks to the rapid growth of newspapers over the period.

Many communicators speak of Misaubin’s frequent newspaper advertisements, but I have been unable to find a reference to any single advertisement for his pills at a time when the newspapers were full of advertisements for pills, potions and concoctions, most notably for the treatment of venereal disease. The papers, perhaps particularly ‘The Grub Street Journal’, whilst busy satirizing the quacks on one page, were only too happy to print their advertisements on another. Paulson writes that at the time of ‘A Harlot’s Progress’, just two years before his death, Misaubin’s name appears frequently in the newspapers in the context of social events (and at least some Masonic occasions), but his pills were ‘not then’ advertised.

Today’s readers must not look at practice in highly entrepreneurial Georgian England by the ‘same standards as those of post-General Medical Council (1858) Victorian and later society. The names of distinguished orthodox practitioners such as Mead and Sloane were associated with advertised medicines, although it is unlikely to have been with their authority. There was normally a great deal of aggressive self-promotion , with no holds barred when it carne to disparaging others.

The regular doctors were often not that much less active in this regard than the quacks. The satirizing of Misaubin which occurred only late on in his career with ‘A Harlot’s Progress’ and ‘The Mock Doctor’ , must be viewed in this light. Misaubin’s financial success and his high society practice incurred professional envy. Fielding writes that it is ‘that Little Pill …which has animated the Brethren of your Faculty against You.’

However his reputation as a quack lived on. with his name and pill for venereal disease (of unknown composition) listed in the curious Phannacopoeia Empirica, without the price given. Martha died in 1749 leaving the secret recipe of her husband’s pill to her nephew Charles.

Misaubin’s death notice in the Gentleman’s Magazine in April 1734, page 218, refers to him as ‘the eminent physician’. Lichtenberg, in his Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings says that Dr Misaubin was quite a good man, only he had rather too high an opinion of a certain powder and certain pills which he compounded in his own establishment; the latter being a sort of edible deer-shot. If death approached one of his customers, very well: he loaded the patient with pills as if with grapeshot and fired. In this way he skirmished and fought many a battle with all possible diseases… I have heard that out of malice (when is that ever absent from merit?) they gave the honest man the nickname of Mice-Aubin. This is because in later years….the good fellow tried his art on rats and mice.

I have found no corroborative evidence that Misaubin did experimental research, but if true it would certainly add another and interesting dimension to the man.

Dr Misaubin, ‘Mizzy’ to His Grace the Duke of Richmond, appears to have been held in high regard socially and in his Masonic connection. He was very well qualified medically with a successful medical practice which clearly attracted the envy of his colleagues. He was a prime target for satire physically, being strikingly tall and thin; he was patently eccentric and a foreigner to boot. He does not, in my opinion, in the context of 18th century medical practice and his own qualifications, warrant the title ‘quack’. It is ironic, however, that it is mainly thanks to William Hogarth’s use of his image to make such brilliant social comment that John Misaubin’s memory lives on.

By B.L.Hoffbrand

SOURCE

Dr John Misaubin: Hogarth’s Huguenot ‘quack’ – by B.L.Hoffbrand , published in its entirety in The Huguenot Society Journal, Vol XXX No.1 – 2013

- Influencia de la Masonería en Chile - April 29, 2024

- Pomegranate in Freemasonry – its significance - March 11, 2024

- Inns and Innkeepers’ incidence in Freemasonry expansion - February 28, 2024