Among the most celebrated visitors to Italy of the 18th c. was the German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman and theatre director, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who dedicated a significant part of his work Italienische Reise (The Italian Trip) to his journey to Sicily, and left us a vivid impression of its inhabitants’ way of life.

Freemasonry officially appeared in Sicily, part of the Kingdom of Naples, in 1768 when England’s leading Grand Lodge in Naples conceded a warrant to the Perfect Union N. 433, which met in Palermo. The Lodge had been established by and for the benefit of military Irishmen under the command of Col. Francis Everard, but in order to survive it soon began to also admit civilians, culminating in Carlo Cottone, Prince of Villermosa, being its Worshipful Master at the end of 1785. There was another lodge in Palermo that operated under the rival National Grand Lodge of Naples, working on the rituals of the Rite Rectifié, successor of the Rite of Strict Observance, but it was in decline.

The Danish philosopher Friedrich Münter and Goethe were among the many Freemasons who in the 18th century visited the enchanting Mediterranean island. They were both disciples of Neo-Templarism and members of the Illuminati sect and had met in Rome. It is unquestionable that Goethe’s eagerness to broaden his Italian experience by visiting Sicily, rose directly from the description that Münter gave him of that captivating place. Goethe claimed he scheduled his trip to Palermo around the middle of March and that he delayed it on at least two occasions, only sailing from Naples on March 29th after he had learned that the vessel’s captain, Filippo Cianchi, was also a Freemason. Turbulence hampered the sea crossing, but Goethe safely arrived in Palermo on the bright afternoon of 2nd April. In Italienische Reise, he described the marvelous sensation he felt when he saw the gulf with on the right the Mount Pellegrino – “the most beautiful promontory in the world,” he called it – and the Conca d’oro on the left (The Golden Shell).

In Palermo, Goethe checked in at Mme. Montaigne’s hotel with the alias Philip Moeller. He hoped that by not revealing his true identity he would stay away from prying eyes, but to his surprise one evening, two men in uniform came to escort him to the Palace of the Viceroy, Francesco d’Aquino Prince of Caramanico. This nobleman had left the Dutch Lodge Les Zelés in Naples in 1769 to become a founding member and first Master of the Well Chosen Lodge, sanctioned by the Grand Lodge of England. He became also the Grand Master of the newly formed National Grand Lodge of Naples in 1773, but he resigned and withdrew from the Craft in 1775, when King Ferdinand IV banned Freemasonry in his realm.

It is unknown who had notified Prince Caramanico of the presence in Palermo, under an assumed identity, of the important German Brother; but it is reasonable to suspect the tip-off came from the Naples Freemasons. Other potential informers are the German landscape painter Jacob Philipp Hackert, who had met Goethe in Naples and had been Prince Caramanico’s guest at Palermo, the English Ambassador in Naples, Sir William Hamilton, and the ship’s Captain Cianchi himself.

Count Statella, the Viceroy’s Master of Ceremonies and a Knight of Malta, greeted Goethe on his arrival at the Palace. According to an anecdote, the Count – believing the visitor was a German called Philip Moeller – made an embarrassing blunder and casually mentioned that he had just finished reading “Werther,” a novel by another German named Goethe, whom he then talked about in derogatory terms. At this point Goethe revealed his true identity much to the dismay of the Count, who was even further embarrassed when the Viceroy, requesting him that Goethe be sat next to him at the table, grinned back at his Master of Ceremonies’ surprised reaction.

Francesco D’Aquino Prince of Caramanico

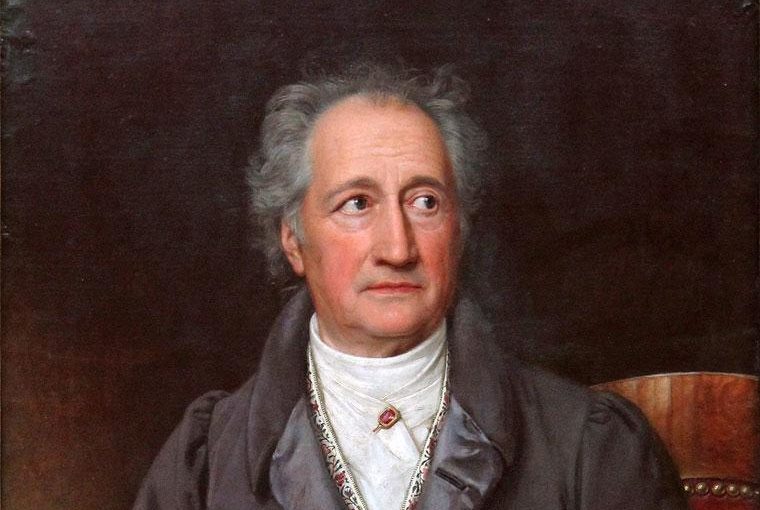

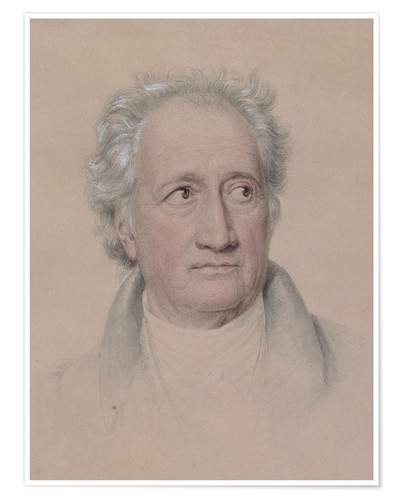

Joanne Wolfgang von Goethe (Frankfurt 28.8.1749 -Weimar 22.3.1832)

By traveling under a false identity, Goethe wanted to avoid contact with anyone from academic circles or high society and thus remain free to fully absorb and enjoy the island’s natural beauty. Despite his best efforts to remain incognito, however, we know he also met and frequented in Palermo the Baron Antonio Bivona, a lawyer engaged by King Louis XVI of France to investigate Giuseppe Balsamo and his family. Balsamo, a self claimed magician and healer who was using the alias Count Cagliostro on his far and wide travels in Europe, had become famous particularly for his frauds and supposed role in Queen Marie Antoinette’s necklace scandal. We know that in March 1787, the Baron had lent his report on Balsamo/Cagliostro to Goethe, who after reading it, visited Giuseppe’s mother and sister on Via Terra delle Mosche, a street in a much run-down area of Palermo.

This time Goethe introduced himself as an Englishman by the name of Mr. Winton, and informed the Balsamos that Giuseppe had traveled to London after being released from the Bastille. Goethe sympathized with the two destitute women, who had a big family to support and in Italienische Reise, he expressed the remorse for not being able to take care of them right away.

Giuseppe Balsamo akas Count Cagliostro

Via della Terra delle Mosche, Palermo, Sicily

According to one account cited by several sources, on his return to Germany, Goethe showed his Brothers of the Order the letter that Giuseppe’s mother had written to her son, in which she begged for financial help. And those generous and caring men, moved by the tragic story, raised a sum of money and conveyed it to the Balsamo women via the English merchant Jacob Joff. The truth, however, may be that which is found in the memoirs of Brother Karl August Bottiger, a well-known archaeologist who knew Goethe and was a member of the Lodge Der goldene Apsel in Dresden. He wrote:

“(…) the amount delivered to the Balsamos was [just] the honorarium the publisher Unger had paid Goethe for his Der Gross-Cophta,” a satire on Freemasonry that was staged in 1791 and proved a failure.

Whatever version of the events you choose to believe, there is no doubt that the financial gift to the the Balsamos was a noble, generous gesture performed in classic Masonic fashion !

After traveling across the island of Sicily, Goethe came to the following conclusion about the locals , which is a strong testament of their bravery:

Messina, Sunday 13 May 1787 – “I thought how interesting it was to see how gentlemen could get together and speak freely and with impunity, under a dictatorial government, to protect their own as well as foreign interests.”

Extracted and revised by the Editor from the paper Goethe in Palermo written by Bro. M.R. Maggiore and published in AQC 1985,vol. 98, page 205-207

- Influencia de la Masonería en Chile - April 29, 2024

- Pomegranate in Freemasonry – its significance - March 11, 2024

- Inns and Innkeepers’ incidence in Freemasonry expansion - February 28, 2024