It is common opinion that Speculative Freemasonry descends from the Crusaders. Such an argument was initially put forward by the Scottish Freemason Chevalier Ramsey in his Paris speech of 1736. But if we are to believe in this theory, how do we explain that Speculative Freemasonry presence on Malta, the very last bastion of those Christian soldiers, was only established around two hundred years ago? The answer lies in the events that history has recorded and in the corrupted nature of man that induced them.

This is the story of the Knights Hospitallers, later known as the Knights of St John of Rhodes and Malta, who belonged to the last surviving Order of the Crusaders.

THE RELIGIOUS WARS

By the end of the first millennium the Arabs presence in the Mediterranean was considerable. With their Caliphate the Moors controlled southern Spain, ruled the North African territories and coastline and were preparing to invade Sicily and Southern Italy. By 1091, they had conquered all of Anatolia – now part of Turkey – and were at the gates of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire that was once part of Rome. In 1094 the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, increasingly threatened by the raising Islamic forces found it necessary to ask for help from the most powerful man in Western Europe of the time, the Pope.

For the Church this was a great opportunity to claim back Jerusalem and the land where Jesus Christ had lived and died, from Islamic control. At the Council of Clermont on 27 November 1095, Pope Urban II delivered a sermon which called for all military men to travel to Jerusalem and reclaim for Christianity, the Church of the Holy Sepulcre, the Temple of King Solomon and all the other shrines that had fallen into the hands of the Arabs in 638. The response was tremendous, further boosted by the Papal Edict stating that “whoever for devotion only, not to gain honour or money, goes to Jerusalem to liberate the Church of God, can substitute this journey for penance”. Wonderful!

No one would have imagined that the aftermath of such an event would have caused ripples in history for the next four hundred years.

The leaders of the First Crusade (1098-1099) were all minor Lords, Barons or their siblings who , unable to inherit their family’s wealth or title, had chosen to turn to the military life and combat. In contrast, the foot soldiers were mostly landless vagrants recently freed from the breakdown of the feudal system. Lacking any sense of purpose in life, those men followed the charismatic Knights to the Holy Land in the belief that they were answering God’s call to fight the infidels.

The leaders of the First Crusade (1098-1099) were all minor Lords, Barons or their siblings who , unable to inherit their family’s wealth or title, had chosen to turn to the military life and combat. In contrast, the foot soldiers were mostly landless vagrants recently freed from the breakdown of the feudal system. Lacking any sense of purpose in life, those men followed the charismatic Knights to the Holy Land in the belief that they were answering God’s call to fight the infidels.

The First of the Holy Wars succeeded in recapturing the City of Jerusalem from the Muslims. The Knights who had enthusiastically answered the Pope’s call, were now at liberty to dedicate their efforts towards conquering territories for themselves and establishing their own little Kingdoms in the Orient. They did so by setting up various City States in both the Holy Land and its surroundings.

They ruled over and traded with Muslims, Christians and Jews of all sects; they gained fresh knowledge from those cultures in the fields of medicine, science and the arts and took all that knowledge back to Europe including secrets of a different nature which it is claimed were discovered under the Temple of King Solomon.

During this period of occupation the Crusaders built castles, many of which can still be seen today, to protect lands and roads. They also organised themselves into various Orders, the first being that of the Knights of the Temple in 1118 with Jacques de Molay as Grand Master.

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was called for by Pope Eugene III and it was started in response to the fall of the City of Edessa [1] in 1144 to the Muslim forces of Zengi. This Crusade became known as the Kings’ Crusade because it was led by Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. The City State of Edessa had been founded during the First Crusade by King Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098; it had been the first of a kind to be established by the Christian leaders and it was also the first to fall to the Muslims. The Second Crusade was a failure for the West, but at least Jerusalem remained in Christian hands. The Muslims fought on relentlessly and after repossessing many of the Christian held Cities, they recaptured Jerusalem in 1187 thus igniting a Third Crusade (1189–1192).

This third military campaign, was partly successful. It fought the army of Saladin and it was led by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa who set out for the Holy Land in 1189. The Crusaders regained control of the coastline and of the important ports of Acre and Jaffa, which were sources of great revenue, but alas! with the death of German King Barbarossa and the defeat of his army, the Crusaders failed to recapture Jerusalem!

On September 2, 1192 the Treaty of Jaffa was negotiated between Richard I the Lion Heart and Saladin. It put an end to the hostilities and it also granted the Christian pilgrims rights of travel in Jerusalem and around Palestine.

After signing the Treaty Richard the Lion Heart, ruler of England, departed the Holy Land and returned home, although his eventful journey took him two years to complete.

THE CRUSADERS AND THE KNIGHTS HOSPITALLER

To join the Crusaders, men were asked to take oaths. They were required to live by strict rules and to observe chastity, fidelity, fasting, self sacrifice, meditation and honour God through daily prayers. But in reality such vows were just a front and were never taken seriously. Initially the Templars Order began as a group of religious-military men who would defend the pilgrims on their journey to Jerusalem from the attacks of nomads and Muslims, but later changed into a military organisation for the defence of those States they themselves had established in the Orient.

To join the Crusaders, men were asked to take oaths. They were required to live by strict rules and to observe chastity, fidelity, fasting, self sacrifice, meditation and honour God through daily prayers. But in reality such vows were just a front and were never taken seriously. Initially the Templars Order began as a group of religious-military men who would defend the pilgrims on their journey to Jerusalem from the attacks of nomads and Muslims, but later changed into a military organisation for the defence of those States they themselves had established in the Orient.

The Knights that fought the Holy Wars came from different parts of Europe and spoke different languages. Over the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, and particularly during the Hospitallers’s occupation of the island of Rhodes, the Crusaders were therefore organised according to a linguistic-geographical criteria. Eight separate districts or “Langues” were established and each had its own quarters or “Auberge”. The common denominator for becoming a Holy Soldier, however, was that the candidate could prove a noble lineage; except in the case of the Germans who were even stricter and excluded the illegitimate sons of Kings. The eight Langues represented the territories of: Provence, Auvergne, France, Italy, Aragon, German, Castile and England.

In 1534 – soon after the fall of Rhodes to Suleiman the Magnificent – King Henry VIII made himself head of the Church of England and began destroying monasteries and seize land – both in England and Ireland – that belonged to the Hospitallers and were the source of a large regular income. Ultimately, the persistent refusal of their Grand Master to recognise the jurisdiction of England over that of the Church of Rome, led Henry VIII to dissolve the Order [2] in 1540. This forced the Knights of the English “langue” in the Holy Land to join their German Brethren and form “The Anglo-Bavarian Langue”.

The Hospitallers are frequently mistakenly described as “monks of war” [3]. In reality they lied somewhere between priests forbidden by canon law to bear arms and crusading warriors who carried out their religious obligation through combat. The English historian Edward Gibbon [4], described the Hospitallers as men who “neglected to live, but were prepared to die in the service of Christ” [5]. The Order of the Hospitallers was the last of the three greatest Orders which had sprung out of the Crusades. The Templars were dissolved by the Pope on 22 March 1312 at the Council of Vienne whilst the Teutonic Knights [6], from Prussia, never recovered from the serious defeat received at the hands of the Lithuanians and Poles at the battle of Tannernberg in 1410. Only the Order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem – aka The Hospitallers – survived and preserved the fire and ardour which had characterised the time of the Crusades. They also had been granted on 2 May 1312, by Pope Clement V’s Bull “Ad Providam”, all of the Templars’ properties (except those in the Iberian Peninsula).

The Hospitallers are frequently mistakenly described as “monks of war” [3]. In reality they lied somewhere between priests forbidden by canon law to bear arms and crusading warriors who carried out their religious obligation through combat. The English historian Edward Gibbon [4], described the Hospitallers as men who “neglected to live, but were prepared to die in the service of Christ” [5]. The Order of the Hospitallers was the last of the three greatest Orders which had sprung out of the Crusades. The Templars were dissolved by the Pope on 22 March 1312 at the Council of Vienne whilst the Teutonic Knights [6], from Prussia, never recovered from the serious defeat received at the hands of the Lithuanians and Poles at the battle of Tannernberg in 1410. Only the Order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem – aka The Hospitallers – survived and preserved the fire and ardour which had characterised the time of the Crusades. They also had been granted on 2 May 1312, by Pope Clement V’s Bull “Ad Providam”, all of the Templars’ properties (except those in the Iberian Peninsula).

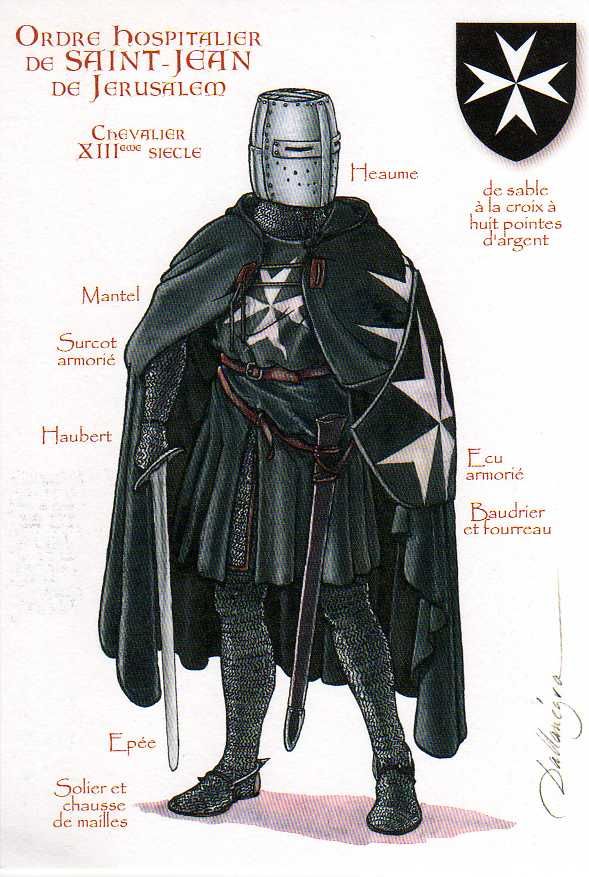

The Hospitallers had continued the tradition of the Cassinese Benedectine monks who in 1070 had established a hospice in Jerusalem dedicated to the well being of pilgrims who were visiting the Holy Land. On their black tunic and cloak the Knights bore a white eight-pointed Cross which was symbolic of the eight beatitudes:

- Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven

- Blessed are they who mourn, for they will be comforted

- Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the land

- Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied

- Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy

- Blessed are the clean of heart, for they will see God

- Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God

- Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven

The four arms of the cross, instead, represented the four virtues; the same that are held in high regard by the Speculative Freemasons and that are recommended to the Candidate in a special part of the Ritual:

- Prudence

- Temperance

- Fortitude

- Justice

The Crusader’s hold of Jerusalem lasted less than 100 years. Under the military  leadership of Saladin, the Muslims recaptured it in 1187 pushing the Crusaders to the coastal city of Acre which became their new headquarters. When Acre fell in 1291. the Crusaders abandoned the Holy Land and retreated to Cyprus , an island where the Hospitallers owned rich estates. Their sugar factory at Kolossi was very profitable and its income went to fund the building and running of the Order’s hospitals. But Cyprus was never meant to be a place of settlement for the Hospitallers and in 1310 the Knights moved to the island of Rhodes which they had captured from pirates. They built strong fortifications both on Rhodes and on the nearby smaller islands and created what became known as “The Shield of Faith”.

leadership of Saladin, the Muslims recaptured it in 1187 pushing the Crusaders to the coastal city of Acre which became their new headquarters. When Acre fell in 1291. the Crusaders abandoned the Holy Land and retreated to Cyprus , an island where the Hospitallers owned rich estates. Their sugar factory at Kolossi was very profitable and its income went to fund the building and running of the Order’s hospitals. But Cyprus was never meant to be a place of settlement for the Hospitallers and in 1310 the Knights moved to the island of Rhodes which they had captured from pirates. They built strong fortifications both on Rhodes and on the nearby smaller islands and created what became known as “The Shield of Faith”.

Rhodes came under constant attack by the Muslims. In 1440 and 1444 it was unsuccessfully besieged by the Mamluk forces of the Sultan of Egypt and in 1480 the first attack by the Ottoman Turks was also repelled. The Ottomans came from western Turkey and had replaced the Saracens as the first Muslim power. After conquering Constantinople – the modern Istanbul – in 1453 they continued expanding and planned to annexe Rhodes. After their attack to the island in 1480 had been warded off, they tried again more convincingly under the command of the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in 1522 and on December 22 of that year Rhodes capitulated.

Rhodes came under constant attack by the Muslims. In 1440 and 1444 it was unsuccessfully besieged by the Mamluk forces of the Sultan of Egypt and in 1480 the first attack by the Ottoman Turks was also repelled. The Ottomans came from western Turkey and had replaced the Saracens as the first Muslim power. After conquering Constantinople – the modern Istanbul – in 1453 they continued expanding and planned to annexe Rhodes. After their attack to the island in 1480 had been warded off, they tried again more convincingly under the command of the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in 1522 and on December 22 of that year Rhodes capitulated.  The Knights and the local population had valiantly resisted for six months whilst the European kings had shamefully only looked on. The Order’s Grand Master, Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam [7] , initially refused to make terms with the Muslims but later managed to negotiate very favourable conditions. The Ottomans let the Knights and the Rhodiots leave the island unharmed and even take with them their treasures, records and weapons. On 1st January 1523 the Knights Hospitallers retreated to Rodos harbour and sailed westwards on a fleet of 50 vessels. The ships were in pitiful conditions and cramped with many wounded Knights, common soldiers and thousands of Rhodiots. They first harboured at the port of Messina in Sicily (Italy) and later at the port of Baia, in the Gulf of Naples (Italy), were they received the news that Pope Clement VII had granted them temporary residence in the city of Viterbo to the north of Rome.

The Knights and the local population had valiantly resisted for six months whilst the European kings had shamefully only looked on. The Order’s Grand Master, Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam [7] , initially refused to make terms with the Muslims but later managed to negotiate very favourable conditions. The Ottomans let the Knights and the Rhodiots leave the island unharmed and even take with them their treasures, records and weapons. On 1st January 1523 the Knights Hospitallers retreated to Rodos harbour and sailed westwards on a fleet of 50 vessels. The ships were in pitiful conditions and cramped with many wounded Knights, common soldiers and thousands of Rhodiots. They first harboured at the port of Messina in Sicily (Italy) and later at the port of Baia, in the Gulf of Naples (Italy), were they received the news that Pope Clement VII had granted them temporary residence in the city of Viterbo to the north of Rome.

The Grand Master Villiers de L’Isle-Adam – fearful that the Order’s considerable and widespread wealth should fall into the hands of envious European Kings and more importantly that any more time spent in exile would lead to the disintegration of the Order, for more than seven years made the round of European Courts pleading for a new home.

Several ports and islands of the Mediterranean were considered and then dismissed as a suitable sanctuary until the choice fell on the highly strategic island of Malta, south west of Sicily. The King of Spain and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire – Charles V – presented it as a gift to the Order in 1530 so that the Knights may“… perform the duties of their religion for the benefit of the Christian community and employ their forces and arms against the perfidious enemy of the Holy Faith”.

In exchange for Malta and in a show of impartiality to all Kings of Europe, the Hospitallers made public submission not to Spain but to its feudatory territory of Sicily, ruled by Charles V’s Viceroy to whom they paid a nominal rent in the form of one Falcon a year. In reality the Knights, in exchange for Malta, were committing themselves to defend the Mediterranean from the Ottomans [8] and in particular to safeguard, for Spain, the sea port of Tripoli[9] in Libya, North Africa, whose control was costing the insular Catholic Kingdom, huge financial and military resources.

Malta was not as close to the Muslim world as Cyprus and Rhodes were and in time of military danger, natural disaster or food shortage, supplies and support would have been quick to arrive from the nearby Christian territory of Sicily. Alas, the events that followed proved that assumption wrong. Unlike in Rhodes, the Knights found themselves unwelcome by the natives. Immediately after their arrival the Maltese nobility decided to withdraw to their palaces in Medna and not to have any contact with the Christian outsiders. The knights settled in the fishing village of Birgu (“Il Borgo”) – just inside the entrance of the Grand Harbour – and made it their headquarters. From there they directed the building of a number of fortifications all round the island which assured their future and prosperity.

and Rhodes were and in time of military danger, natural disaster or food shortage, supplies and support would have been quick to arrive from the nearby Christian territory of Sicily. Alas, the events that followed proved that assumption wrong. Unlike in Rhodes, the Knights found themselves unwelcome by the natives. Immediately after their arrival the Maltese nobility decided to withdraw to their palaces in Medna and not to have any contact with the Christian outsiders. The knights settled in the fishing village of Birgu (“Il Borgo”) – just inside the entrance of the Grand Harbour – and made it their headquarters. From there they directed the building of a number of fortifications all round the island which assured their future and prosperity.

The hospital was a characteristic institution of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. The Knights felt it was their duty to build one wherever they stayed and they attended the sick at least once a week. On Malta they erected a hospital at the south east side of Valletta which cared for the natives as well as for the many sick people who came from Sicily and southern Italy. To run the medical institution, the Hospitallers spent a considerable part of their funds whilst the rest went towards the cost of building Churches and maintaining and equipping their ships and garrisons. Essentially half of their revenue was directed to such projects but the finances of the Order of the Hospitallers – now known as the Knights of Malta – were so large that it never mattered; not at least until the French Revolution took Europe by storm in 1789.

THE SIEGE OF MALTA AND THE FALL OF ST ELMO

Malta had become a thorn on the side of the Ottomans who were desperate to neutralise the island’s maritime supremacy. In contrast to the Templars, who had remained a military Order dedicated to fighting the Muslim infidels on land, the Hospitallers had intelligently adapted to times. During their occupation of Rhodes, they had transformed themselves from a nursing Brotherhood that cared for the sick and wounded, into the finest and most feared seafarers the Mediterranean had ever seen.

Suleiman the Magnificent did not tolerate that the descendants of the Knights he had allowed to abandon Rhodes alive – in a gesture of leniency and admiration for their courage – should again be in a position to threaten Islam. The Priory of the Knights of St John’s reports that an advisor to the Ottoman’s ruler, the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, wrote to him in these terms:

“So long as Malta remains in the hands of the Knights, so long will every relief from Constantinople to Tripoli run the danger of being taken or destroyed. This cursed rock is like a barrier interposed between your possessions.”

Malta, the pest of the Mediterranean, the island on which prisoner Turks were being sold at slave markets, had to be conquered and the Order of St John be annihilated!

Jean Parisot de la Vallette [10] succeeded the Grand Master De La Sangle on his death in 1557. He had been a Knight of St John all his life and he was in charge of the defence of the island from the expected Ottoman’s attack in the spring and winter of 1565. In response to his plea for help made to the various Kings of Europe, La Vallette had received 10,000 crowns from the Pope and some troops from King Philip II of Spain, son of Charles V. In addition the Order could count on 9000 men of whom 600 were fighting Knights, volunteers from Italy plus the Maltese soldiers and galley slaves. In contrast, the Turks had 180 ships and between 30 to 40 thousand men.

Jean Parisot de la Vallette [10] succeeded the Grand Master De La Sangle on his death in 1557. He had been a Knight of St John all his life and he was in charge of the defence of the island from the expected Ottoman’s attack in the spring and winter of 1565. In response to his plea for help made to the various Kings of Europe, La Vallette had received 10,000 crowns from the Pope and some troops from King Philip II of Spain, son of Charles V. In addition the Order could count on 9000 men of whom 600 were fighting Knights, volunteers from Italy plus the Maltese soldiers and galley slaves. In contrast, the Turks had 180 ships and between 30 to 40 thousand men.

On May 18th 1565 the Ottomans disembarked on the island. They were armed with artillery which proved terribly effective. The walls of St Elmo – a fort of strategic importance – soon began to crumble under the constant Ottoman’s bombardments. The Knights despatched one messenger to inform the Grand Master La Vallette that help was needed. But the Grand Master, disbelieving the report, procrastinated by sending two of his own knights to check out the situation on the ground..

On May 18th 1565 the Ottomans disembarked on the island. They were armed with artillery which proved terribly effective. The walls of St Elmo – a fort of strategic importance – soon began to crumble under the constant Ottoman’s bombardments. The Knights despatched one messenger to inform the Grand Master La Vallette that help was needed. But the Grand Master, disbelieving the report, procrastinated by sending two of his own knights to check out the situation on the ground..

When on 16th June La Vallette at last decided to send the reinforcements, it was too late; the Ottomans had delivered a great assault to the Fort of St Elmo from three of its sides. Time after time the Islamic forces attacked and time after time they were repelled by the exceedingly valiant Knights. On 22nd June 1565, the day of the Feast of Corpus Christi which the Knights never failed to honour, the sixty or so survivors put aside their swords and went to mass dressed in the formal dark robes of the Order. They received the Holy Sacraments in the Chapel, encouraged and embraced one another and made themselves ready to die! The Muslims started pouring through the breached walls and down the little lanes of the citadel, advancing like a human sea to the heart of the fortress. The deputy commander De Guaras attempted to stem the enemy’s advance but his head was cut off his shoulders by a scimitar hit.

The two Italian knights defending with him – Le Mas and Paolo Avorgado – were also killed and cut to pieces. Amongst the other heroic knights of St Elmo defence was its Governor Luigi Broglia from Piedmont, Italy – a Knight of over seventy years of age! – his assistant Giangiacomo Parpalla and the Chevalier Melchior from Monserrat, a Knight of Aragon who took over from Luigi Broglia when the latter was seriously wounded. As the end neared, the Italian Knight Francesco Lanfreducci hurried on a turret to light a fire; the agreed signal that said all was lost.

On the morning after the battle, the sea current swept into the Grand Harbour the body parts of the knights who had been dismembered by the Janissaries[11]. Floating on the water were the headless bodies of four knights stuck on crosses, two of which were identified as being Giacomo Martelli and Alessandro San Giorgio from the Italian “Langue”. The Grand Master La Vallette wanted revenge and gave orders to kill all Muslim prisoners, throw their bodies into the sea and shoot their heads into the enemy lines from the cannons of the Fortress of St Angel. It was an unequivocal message to the Muslim forces that the Knights that the Knights were willing to fight to their death rather than fall prisoners.

One thousand and five hundred Christians died against an estimated Islamic loss of eight thousand men. One hundred and twenty Knights and servants-at-arms perished in the battle with thirty one of them coming from the Italian Langue. Only nine knights survived the battle of St Elmo and were taken prisoners; they were a Frenchman, five Spaniards and three Italians: Pietro Guadani, Francesco Landreducci, Bachio Craducci. Prisoners of war were worth more as hostages to the Muslims as they could demand a ransom for their release. but many of the Muslims spared no one in the battle of St Elmo, determined as they were to revenge the great losses they had suffered. Even the Knights who had been taken prisoner seemed to have vanished from the records, perhaps slaughtered.

With the fall of St Elmo on 23rd June 1565, the fight moved on to the fortress of St Michael and on 7th August the Muslims made a joint attack both by land and by sea. The Muslims had managed to bore a tunnel under the ramparts of the bastion and with the use of explosives they had blown a huge gap in the walls which had allowed them to enter and threaten Il Borgo. The Grand Master Parisot de Valette and his Knights, refusing to retreat to Fort St Angelo, launched themselves into the fight and managed to repel the attacks which took place both in daylight and during darkness.

But on hearing of the fateful event, the little garrison in Mdna – also known as La Citta’ Nobile or Citta’ Vecchia – attacked the Muslims from behind burning and killing all they found in their way. The rumours began to spread amongst the Ottomans that the reinforcements from Sicily had arrived and the bulk of the Muslim forces, just as at the north of the island the Bastion of Castille in the Spanish Auberge was ready to fall, decided to withdraw! After all , with the exception of St Elmo, all the other fortifications on the island were still standing and their breached walls were being efficiently repaired by the Christian garrisons working day and night.

Furthermore, with the onset of the hot weather sickness began to sweep through the besieging Muslim troops, ammunition and food were running low, jealousy and lack of cooperation were spreading inside their camps. In the midst of all this, the reinforcements from Sicily had finally arrived and landed unnoticed in Melleha Bay! Believing that the Christians now outnumbered them, the Muslims prepared to return home. On 8th September the bulk of the troops boarded their ships and sailed away only to be recalled back on land by their Command that had belatedly assessed the troops from Sicily consisted of a mere 8,000 men. But it was too late. Fifteen thousand men were already on the ships high at sea; the unfortunate troops left behind were slaughtered by the Christian forces.

For Suleiman the Magnificent, this war had proved a most inglorious way of ending his reign.

Malta had survived the last Turkish assault and Europe could celebrate the last epic battle of the Crusader Knights. Malta went on to retain its independence, under the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, for another two hundred years during which time merchants and Knights from all over Europe and the Mediterranean flocked to La Valletta swelling its population threefold. The Order’s ability to balance the rules as a religious, military and medical organisation, however, enabled it to continue to exist.

THE DECLINE

After the siege of 1565, the Hospitallers moved their headquarters away from Il Borgo and in March 1566 they began building the town of La Valletta which the Knights made their nerve centre. They ruled Malta as an independent State although being ultimately subject to the Pope’s authority. The Order melted its own coins and received European Courts Ambassadors. In the 18th century the Grand Master Manuel Pinto de Fonseca even assumed a monarch’s crown.

The period in history that had followed the Hospitallers’ arrival on the island of Malta was influenced by the wars that France and Spain fought against each other throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. They put an enormous stress on the Order whose harmony was tested to the full. Nevertheless the Spanish and French Knights Hospitallers did manage to retain some neutrality and continued waging war against the Ottoman Empire.

Besides having exhausted their wealth to build La Valletta, the Order had began to suffer continuous internal disorder and disobedience. The highest source of income was coming from France and the French Knights were thus indirectly influencing, much to the displeasure of their Spanish Brethren, the decisions taken by the Grand Master of the day. In the almost anarchic conditions instituted, some of the Knights broke the vows of chastity and had intercourse with the native women whilst others enrolled as mercenaries for a taste of adventure. The events that took place in the 18th century Europe changed the Order’s role. Its defensive importance in the Mediterranean lessened and some Knights became inward looking and concerned with “status” and promotion. Indeed senior Knights could have their own households instead of living communally and advancement also rewarded them with profitable offices and lands.

But while the Hospitallers were fighting the Muslims wherever they would find them, the Kings of Europe had began focusing across the Ocean for commerce. France and Spain, realising they could bring more wealth back from the New World, abandoned Malta to its destiny. If the Muslims had again decided to attack, they would have found very few Knights with the desire and strength to fight them. Most of the population of the island had changed and was now made up of the Knights of Rhodes’s illegitimate children. The natives resented the Order for its contemptuous treatment of the population; the taxes were high and the Knights mistreated the local women by turning them in sexual objects. For the Knights of St John, the journey into decadence had just began.

The Knights’ last heroic operations came when Ibrahim I declared war on Venice which was now the only power in the Med that continued to resist the Ottomans by controlling the island of Candia (Crete). The Hospitallers joined forces with the Serenissima and under the command of Admiral Mocenigo were successful in recapturing the islands of Lemnos and Tenedos in the Aegean Sea.

and under the command of Admiral Mocenigo were successful in recapturing the islands of Lemnos and Tenedos in the Aegean Sea.

But eventually the might of the Ottoman Empire overcome even that of Venice, although the Muslims never dared attack the city itself.

The Enlightenment movement in Europe of the 18th century had a profound impact on the Hospitallers. In the autumn of 1789 the French King Louis XVI’s finance Minister, Necker [12] , had appealed to the landowners for a voluntary contribution to the Crown. The French Monarchy was the principal protector of the Order and so the Aristocrat French families came forward to donate 500,000 francs to the destitute King. Immediately after that gesture, the Constituent Assembly declared the Order of St John to be a foreign power that, by possessing properties in France, was liable to pay all taxes. More shockingly the French Knights of the Order were divested of their citizenship. Three years down the line all their properties had been confiscated, leaving the Order with limited resources for the defence of Malta in the face of a constant threat of invasion.

In 1798 Napoleon, on his way to the Campaign of Egypt at the head of a fleet of between 450 and 600 ships, sent out a request to the Grand Master of the Order for permission to dock his ships and let his men have some refreshment.

The Grand Master first refused then let Napoleon know that under the two Countries’s Treaty no more than four ships at the time could enter the harbour. Napoleon, who had merely been polite in asking the question, lost his patience and threw down the mask. During the night of 9th June 1798 Napoleon landed his forces at four different locations of the Maltese Islands: St. Paul’s Bay, St. Julian’s and Marsaxlokk on mainland Malta and the area around Ramla Bay on Gozo and 24 hours later the Grand Master of the Order Von Hompesch , surrendered. Malta had capitulated without much of a fight!

Napoleon abolished the Order of the Knights of Malta – by which name the Knights Hospitallers had become known – and confiscated its treasure, ships, artillery and properties.

The Knights and the Grand Master were all granted a pension and those who were entitled, received back their French citizenship so they could return home. Others chose to move to Russia whose Tsar Paul I had promised the Order a revival. He gave it many properties and privileges and took control of the Order by electing himself Grand Master. When the Tsar died in 1801 without having fulfilled his promises , the Pope Pious VII named his own Grand Master. On the death of the latter, however, the Russian branch stopped accepting rules from Rome and , according to some sources , the schismatic Russian Order ended up being incorporated into the Orders of the Communist State after the Revolution of 1917. Those other Knights who had been expelled from Malta by Napoleon but had chosen neither France or Russia, went to set up their headquarters first in Sicily (Catania and Messina) then in Ferrara in 1826 and in Rome in 1834. It is in the Eternal City that the Order of the Knights of Malta continues to these days purely as a Catholic Order dedicated to the function of hospitality and charity.

The Order is recognized by the Pope and it enjoys the status of a sovereign nation, holding diplomatic relations with many Countries but its statutes were reformed on 1966 and its military character abolished.

In 2013 the Order’s Grand Master said: “As members of a religious lay Order, we commit ourselves to the relentless task of being not only on the side but also at the side of those who need help and a caring friends in times of crisis in their lives. (…) We were there yesterday; we will be there tomorrow, the day after and for as long as the need remains” [13]

When Napoleon had occupied the island he had found only two warships , one frigate and four galleys in the port of La Valletta out of what had been the most feared and successful fleet of the Mediterranean . Commenting on the fact that the French were lucky not to have been given a hard time by the Knights if they had decided to retrieve to their impregnable fortifications, Napoleon is reported to have said to his generals: “The knights did nothing dishonourable; nobody is obliged to do the impossible (…) the capture of Malta was assured to me well before we left Toulon”. The Knights Hospitallers had betrayed the independence of Malta to France for a few riches!

Their rule of the Mediterranean was over and the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, in its form of military Christian Soldiers who had descended from the Crusaders, vanished forever.

The English Branch of the Order was reconstituted on Jan 24 1831 with Sir Robert Peat as its Grand Prior. The Order has since devoted itself to the succour of the sick and wounded and has rendered a magnificent contribution to saving lives with its ambulance service, during the two world wars.

SPECULATIVE FREEMASONRY IN MALTA

The island of Malta was governed by the French military until a rebellion of the people supported by the English navy drove the French away in 1800. Malta remained an occupied territory of England until 1964 when it became an independent Nation.

It was with the arrival of the English that Speculative Freemasonry made its appearance. The United Grand Lodge of England Obedience, however, became present only with the establishment in 1815 of the Lodge of St John & St Paul No. 349. By 1899 there were seven English lodges on the island and an estimated 1500 Freemasons. From then on Freemasonry grew in number but nothing of any particular importance can be reported. A permanent and big enough Headquarter was at last found in 1907 at the address of 6/7 Marsamxett Road in Valletta and it has remained there ever since.

It was not until 2004 that the Sovereign Grand Lodge of Malta was formed. Prior to that there were three Grand Lodges present on the island, that of England, Scotland and Ireland. Before proceeding to forming a Sovereign Grand Lodge, the Masonic protocol calls for a chosen Lodge to be consecrated first. In Malta that Lodge came from Irish jurisdiction and it was named rather inappropriately “The Hospitallers Lodge” Number 931 before its consecration as the Sovereign Grand Lodge of Malta. It currently enjoys eleven lodges under its independent jurisdiction.

When the Hospitallers abandoned Malta in consequence of Napoleon’s occupation, the association of the island with the Crusaders ended. Neither the late Knights of St John’s in London, the Knights of Malta in Rome or the Speculative Freemasons of the Sovereign Grand Lodge of Malta can claim to have any connection with the original Order of the Knights of Malta and Rhodes akas The Order of Knights of St John’s akas The Order of the Hospitallers.

Does this story demolish the Chevalier Ramsay’s theory that the Speculative Freemasons descend from the Crusaders ? No it does not.

Those Templar Knights who had returned home after the Crusades and had later managed to escape from King Philip Le Bel of France’s purge and Pope Clement V ‘s crackdown, dispersed themselves in Europe and beyond.

A number of those Crusaders found shelter in Scotland which was ruled by an anticlerical monarch, King Robert the Bruce and was therefore out of reach from Rome. By infiltrating the local Guild of wall builders those Knights were able to pass themselves as operative masons and keep a low profile until better days. The dualism of “knight-builder” is exactly what the Chevalier Ramsay refers to in his speech when he said: “(…) the word Mason must not be taken in a literal and material sense as if our founders had been simple workers in stone (…) They were not only skilful architects but also religious and warrior Princes who designed, edified and protected the living Temples of the Most High. And whilst they handled the trowel and mortar with one hand, in the other they held the sword and the buckler”.

Nothing better than the beautiful Roslyn Chapel near Edinburgh comes to mind to support the evidence of a Templars’s presence and artwork in Scotland. Those Knights maintained alive their secrets, philosophy and traditions through the foundation of the Masonic Scottish Rite which they took to France when, many years later, some of them made a safe return.

It is those Knight Crusader that we can salute as being our ancestors rather than, to the disappointment of some, the highly respected and fearsome valiant Hospitallers.

As for the Orders of the Knights of St John and of the Knights of Malta, neither has any link to the Hospitallers and neither can claim to be our precursors.

by De La Riviere

The author forbids any reproduction or publication of this article, in full or in part, without his explicit authorisation.

[1] The city of Edessa and its State had been founded during the First Crusade by King Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098.

[2] In 1557 Queen Mary Tudor, the daughter of Henry VIII, reinstated the Order but Elizabeth I revoked her Act.

[3] D.Seward, The Monks of War: The military Orders, London 2000

[4] Edward Gibbon, (born May 8 [April 27, Old Style], 1737, Putney, Surrey, England—died January 16, 1794, London), English historian

[5] D.Womersley (ed.) Edward Gibbon- The History of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, London 1994, vol 6, pp 609-610

[6] The habit of the Order was a white robe with a black cross. Teutonic Knights was a German military religious Order founded (1190–91) during the siege of Acre in the Third Crusade. It was originally known as the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. Mary of the Teutons in Jerusalem.

[7] The respected, oldest and greatest Grand Master the Order ever had

[8] The Ottomans were Muslims from Turkey

[9] A Christian outpost in the middle of the hostile Muslims States

[10] Jean Parisot De La Vallette was born in 1494 of a noble family of Quercy, France.

[11] The term Janissary, derives from the Turkish word “yeni – cheri” [new militia]. This special force, was the true elite of Turkish army

[12] Jacques Necker , born 30September 1732, died 8April 1804 ,was a banker of Swiss origin

[13] M. Festing, Sovereign Military Hospitallers Order of St John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta Activity Report, Rome, 2013.

SOURCES

“The Sovereign Military Hospitallers Order of St John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta” a paper by Emauel Buttigieg

“Are the Members of Freemasonry Knights of Malta?” by Atila , October 14, 2014 (https://www.traditioninaction.org/Questions/F068_Malta.htm)

“The Masonic Hall in Valletta” – http://englishfreemasonryonmalta.org/html/masonic-hall-valletta.html

“The Illustrious Order of the Hospitalers & Knights of St John of Jerusalem” by John Corson Smith,, Past Grand Commander Knights Templar & Knights of Malta, Chicago 1984

“The Transition from Templars into Freemason” by L. M. , Tetraktys , April 2017

- THE FRACTURED LODGE - February 14, 2026

- Robert Burns – A Poet and a Freemason - January 2, 2026

- HIS MAJESTY’S SERVANT DAVID GARRICK – A FREEMASON ? - June 7, 2024