London was the 18th century wonder capital of Europe. It had been rebuilt following the Great Fire of 1666 and had an extremely new look. The merchants had withdrawn from the City and moved into fashionable terrace houses in the parishes of Soho, Mayfair, and in St. James, which had broad streets and paved squares.

And yet, London continued to be surrounded by miasma and be a city broadly tarnished by horse-dung. In the absence of an adequate sewerage structure, many servants still discharged their master’s chamber pot upon the heads of passersby and because of the coal burning in the fireplaces, layers upon layers of black soot coated the buildings and made the air not healthy to inhale. Violence and street crime were rampant.

THE WORLD OF THE OPERA IN LONDON

It was in this almost surreal habitat that deep connections were established between Freemasonry and the world of music, and they have never been stronger than during those years.

With the upper social classes having so much available time in hand and a strong love for entertainment, London turned into a Mecca for foreign artists. Since 1708, the Italian Opera had been constantly performing, with varying fortunes, at the Queen’s Theater in Haymarket, London, which is now called Her Majesty’s Theater. Built in 1705 and renamed the King’s Theater in 1714 upon the ascension to the throne of Great Britain of the German born George I (1626-1727), the theater also became identified for a period as The Italian Opera House.

The ceaseless comings and goings of French, German and Italian musicians, singers and impresarios continued strongly into the following century and the King’s Theater audience was never entertained with as many comic operas as it was in the season 1768-69.

The international artists all detested the English climate, which brought them colds and fevers, but they never regarded this poor factor as a reason for not coming back if awarded a contract. Aliens had also learned to put up stoically with the infamously atrocious English food and an Italian representative of the 1763 King’s Theater recounted his experience of it in these terms:

“In this expensive metropolis, we poor Christians are reduced during Lent to the melancholy alternative of either fasting like our founder, or living on rotten eggs, stinking fish, train-oil, and frost-bitten roots and herbage’’.

The old King’s Theater

The current Her Majesty’s Theater

HOSTILITY TOWARDS FOREIGNERS

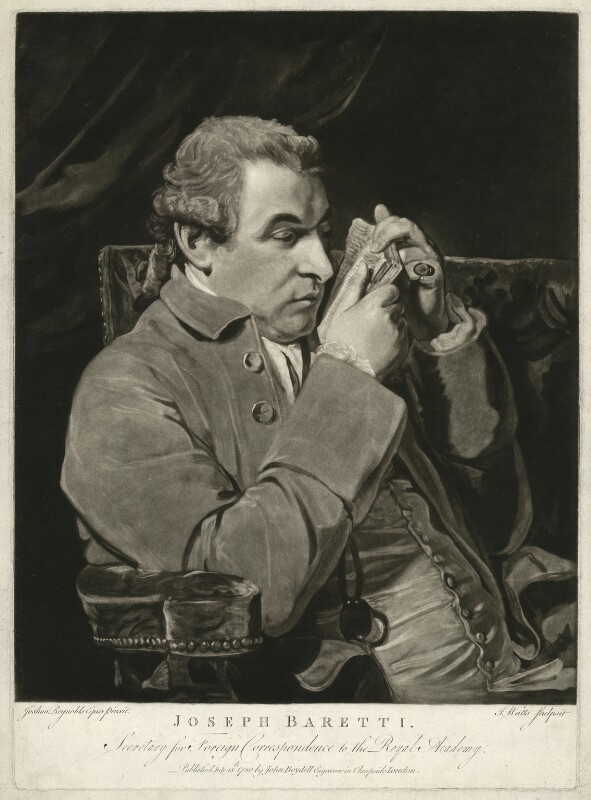

The Italian literatus Giuseppe Baretti (1719-1789), compiler of the first English-to-Italian vocabulary, devoted most of his life in London and denounced the poverty that existed among Italian singers in London, which was created by inadequate earnings and exceedingly costly existence. He did so in a letter printed in The Public Ledger of 16 September 1760, which received this response:

“We can now see into the penury and meanness of those who have gained thousands by our folly and extravagance – we know, while in England. how miserably they live, because they will save all they can to spend in their own country; (…) such is their hatred of the nation that caresses them, that if it were possible to live upon the dirt or filth of the streets, they would rather do it than the least farthing should come back again into an Englishman’s pocket“.

The London society, had always harbored animosity towards aliens–the 1666 Great Fire of London was attributed on a French catholic, after all – and accused the Italians of avarice for their meager spending, neglecting that the aristocrats kept artists waiting around without work or payment for days or even weeks at a time. They did not understand the struggles the touring musicians suffered and would not have cared less even if they did.

Samuel Johnson declared that in London one discovered the “full tide of human existence,” and that although the Capital of England was “a place with a diversity of greed and evil (…) slight vexations do not fix upon the heart” of its residents. In my opinion, he never asked them.

THE NINE MUSES LODGE

Networking was an important chore for all the foreigners who visited England, whether they were artists, merchants, aristocrats, or rich gentlemen. At best, it assured admittance into affluent and patrician circles, at worst it guaranteed contracts and even a profitable office.

And what better way to network than by joining a Masonic Lodge?

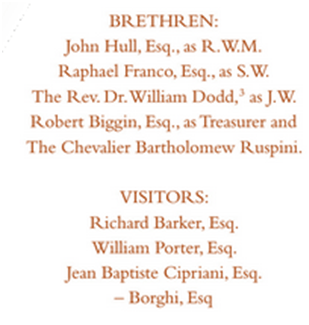

On January 14, 1777, these individuals convened in the Thatched House Tavern on St. James’s Street, Westminster–which at the time was regarded as being part of the County of Middlesex – and on the 23rd, after securing a warrant, formed the Lodge of the Nine Muses No. 502.

With its greatly singular membership made up of leading personalities from the arts, services, and public life from all over Europe but with a majority presence of Italians, the Nine Muses turned into one of Freemasonry’s most fashionable lodges.

From its list of members of this Lodge, the names that immediately grasp our attention are those of three intriguing Freemasons: the condemned felon Reverend D. William Dodd (1729-1777), the German painter Johann Zoffany (1733-1810) and the Italian benefactor and founder of the Masonic School for Girs Chevalier Bartolomeo Ruspini (1728-1813), whose stories I invite you to read. The names of the musician Luigi Borghi and of the painter Giovanni Battista Cipriani (1727-1785), founder of the Royal Academy of Arts, also show up in the Lodge’s minutes, and although entered as visitors, the two were later initiated into Freemasonry.

LUIGI BORGHI (Bologna 1745–London 1806)

Luigi Borghi was a viola player who learned music under the Italian Maestro Gaetano Pugnani (Turin 1731-1798), who was renowned for playing in all of Europe’s principal concert rooms and theatres. Pugnani was made a Freemason in 1768, by the Turin-based Lodge “Saint-Jean de la Mystérieuse,” an offshoot of the Savoiard Lodge Saint Jean des trois Mortiers of Chambery. He came to London on separate occasions between 1767 and 1770 and had contacts with J.S. Bach’s son, Christian, and with Felice Giardini (1716-1796), who were both performing arts entrepreneurs and members of The Nine Muses Lodge.

Borghi came to England in 1774 under contract to play the violin and the viola. Luigi’s career in London was aided by the accolades bestowed upon him by the famous Scottish music score editor William Napier; but in practical terms Borghi benefited considerably better from his friendship with the German wonder violinist Wilhelm Cramer (1745?-1799). Cramer was a member of The Royal Society of Musicians and long-time rival for the title of best violin in England, of Felice Giardini who was an Italian Freemason. Cramer selected Borghi to play the second violin in his quartet that performed at the renowned Bach & Abel Concerts, in Hanover Square. It is significant to acknowledge that both these two artists were also members of the Nine Muses Lodge and that Cramer directed the Court Concerts at Buckingham Palace and Windsor and was for a while the manager of the Italian Opera at the Pantheon.

Three years after Borghi had left London for home, the Italian musicians A.M.G. Sacchini and V. Rauzzini invited him back to play in a concert at the Hickford Room on Brewer Street, in London’s West End, but considered Middlesex at the time. Thanks to an insurance policy underwritten at Lloyds in 1777, we know Borghi went to live in an apartment he had purchased on Charles Street, a neighbourhood in which even Giardini and J. Christian Bach (1735-1782) resided.

As proof of the close relationships that existed between music and Freemasonry, Bach & Abel staged the Concert of April 3, 1778 – in which featured performances by Giardini, Cramer and many others – in the original Freemasons’ Hall. This is the structure in Great Queen Street that can be seen crammed between the Grand Connaught Rooms and the Grand Lodge. Its distinctive architecture will instantly draw your attention.

In 1782, Luigi Borghi relocated to John Street, which was merely a small distance from the Pantheon, whose directors included Giardini (1774-1779) and Cramer. This London’s new musical shrine was erected on a plot of land on the south side of Oxford Street, near Soho. It was to become a “Winter Ranelagh” in the heart of London and contend with Carlisle House, where the Venetian entrepreneur Teresa Imer–alas Mrs Cornelys–organized for many years popular concerts and masquerade evenings for the gentry. Erected in 1772, the Pantheon burnt down to the ground after merely one complete season in 1792; it was rebuilt in 1795 but could not revive its fortunes.

For several years Borghi played at the King’s Theater under Giardini’s management and when in 1783, he composed the Opera Quarta: Six Solo for a Violin and Bass, the design of the Concert tickets was given to the distinguished Italian draftsman and excellent engraver Francesco Bartolozzi (1727-1815), also a member of the Nine Muses.

In 1784, Luigi Borghi played the second violin at the Handel Memorial Concerts held in Westminster Abbey and also, in May and June of the same year, at the Pantheon. On July 2, 1785, the Royal Society of Musicians accepted him as a member. Admission into this society was regarded as outstandingly important, for it not only gave Borghi a formal acknowledgment in the eyes of the world of his genius and contribution to music, but–and perhaps more notably in those days – gave a degree of shelter against hard times. In England, prior to the establishment of the welfare state, professional artists who had fallen to the lowest spoke of fortune’s wheel and their ill or old dependents could benefit from a degree of financial support from the Society acting as a benevolent institution.

Borghi released his Six Overtures, Op.6 in 1787 and dedicated it to the Duke of Dorset, John Frederick Sackville, British Ambassador at Versailles and in the following year he travelled to Munich and composed a violin concert when in Berlin. He returned to London in 1790 and played the violin at the Pantheon in the orchestra of the London Opera Company, of which Borghi became acting manager in the ensuing year, staging between 17 February and 19 July 1790, none less than 55 operas and ballets.

In the season 1791-92, playing in the Opera Buffa with the tenor Guido Lazzarini, was the soprano Signora Anna Casentini (17??-1797) whom Lord Mount-Edgcumbe described as “a pretty woman and a genteel acrtress”. Known also as The Lucchesina, or the little girl from Lucca, Tuscany, she was taking a salary of 700 pounds. According to narrative, when she learned that the co-artist Mme Mara was being paid the larger sum of 1000 pounds from the same company for her role in an Opera Seria, she seduced and married the manager, Luigi Borghi, in a rather curious move to level up the score. The couple then moved into No. 14 Hanover Street, London.

In 1793-94, Anna Casentini was singing in three Operas at the Kings Theater, rebuilt in 1791, as Signora Borghi in three Operas. But that season marked the conclusion of her career in London as her voice was regarded too weak for the truly large new King’s Theater to which the Company had returned from the Pantheon. Given that she passed away three years later, after performing for the last time in Vienna in Semiramide, it is possible that she was ill with consumption, a disease that claimed more lives in Georgian England than any other.

The only information we have about Luigi Borghi’s later life is that of the German 20th century musicologist Arnold Schering, who claimed that the musician died in London in 1806.

The Nine Muses Lodge lost many of its members as a result of a string of circumstances which begun with the death of Christian Bach in 1782, continued with Giardini’s departure for St. Petersburg in 1792 and with Wilhelm Cramer’s bankruptcy.

The Lodge slipped into a steady decline after a highly profitable 1787 that saw the admission of several Italian artists. In that same year, Ruspini’s son James Bladen- a surgeon in Pall Mall- joined the Nine Muses, followed by his brother William–a dentist in St James’–in November 1800. In 1801, there are just 4 new entries in the records and a solitary one in 1802.

A rebound occurred in 1814, but the Nine Muses no longer was a lodge for aristocrats and artists from Europe and Italy in particular. It now meets in Freemasons’ Hall on Great Queen Street, as Lodge number 235. Its history book–An Account of the Lodge of the Nine Muses from 1777 to 2012 – which past lodge Worshipful Masters wrote by using data extracted from past meeting minutes, is a remarkably interesting reading and inspired me to write this article.

The author forbids any reproduction or publication of this article, in full or in part, without his explicit authorization

SOURCES

- Encyclopedia Treccani

- The Lodge of the Nine Muses No.235

- Archive.org

- Academia.edu

- De Homiminis Dignitate – GLRI – Year XIX N.17 – 2019

- MUSIC AND THE CRAFT – LUIGI BORGHI , A FREEMASON OF THE NINE MUSES LODGE - October 31, 2022

- SPILSBURY – THE FREEMASON FATHER OF FORENSIC SCIENCE - April 18, 2022

- THE MASONIC GLOVES - March 21, 2022