In the 18th century, actors were known as His Majesty’s Servants and were entitled to wear (…)

To read WBro Leonardo Monno’s full article, click on the link below:

In the 18th century, actors were known as His Majesty’s Servants and were entitled to wear (…)

To read WBro Leonardo Monno’s full article, click on the link below:

A lo largo de los años la palabra “masón” se ha ido retorciendo a través del tiempo, desde formar organizaciones secretas que son dueñas del mundo hacer tener en control el poder tanto político como económico. Una de las preguntas más desafiantes que me ha tocado desafiar es ¿realmente todas estas especulaciones son verdaderas?,¿los masones son en verdad lo que dicen ser? A lo largo de las investigaciones que hice, lo único que encontré fueron más preguntas de las que esperaba encontrar.

Vamos a empezar con lo esencial ¿Qué es la masonería?

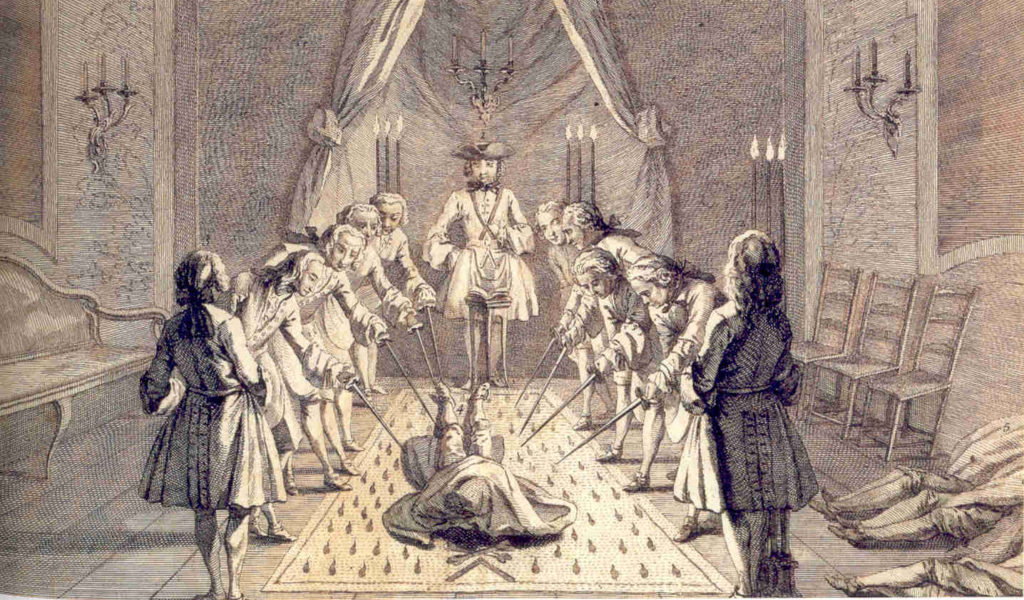

La masonería es una sociedad secreta que junta a varios individuos con un sentimiento de fraternidad. El objetivo principal que tienen es la búsqueda de la “absoluta verdad”, creen que con el encuentro de la verdad el hombre evolucionara en todos los aspectos. Ellos tienen un templo al cual le llaman logias y también le llaman así al grupo de masones que se reúnen. Hacen un tipo de “cultos” que son llamados tenidas, ahí se encuentran todos los miembros una vez al mes, pueden hacer el ritual apropiado para iniciar a los nuevos miembros, ascender de rango a un miembro y/o debaten sobre los temas simbólicos y sociales. Todas estas reuniones son bastantes decoradas ya que los masones son bastantes cuidadosos en el tema de la decoración, en sus encuentros se puede observar como tienen todo muy bien mantenido, hasta se enfocan en el ámbito de la música ya que contratan a orquestas profesionales para sus encuentros de aniversario (la tenida que describo se llama “Gran Tenida Blanca por el 192 Aniversario Patrio” toda recomendación que dé, al final del texto pondré los links para acceder a ellas). Ustedes se preguntarán ¿Por qué son tan detallistas los masones?

Los masones no son los únicos en fijarse en los detalles de sus encuentros, todas las religiones y métodos de creencia son detallistas ya que si encuentras un lugar todo sucio nadie va querer entrar ahí, no llamaría demasiada la atención y obviamente se requiere más miembros porque cada creencia quiere abarcar la mayor gente posible, sin embargo, queda otro punto más ya que los masones no buscan a cualquier persona, buscan a individuos con ciertas influencias o sino no tendría el poder que tienen ahora, y ¿Qué tiene ver el último punto con ser detallistas? Evidentemente todo esto es una táctica, porque eso demuestra el poder que tienen los miembros unidos. Es increíble como los menores detalles influyen en todo esto.

Ahora vamos a la parte más etimológica de lo que nos convoca hoy día. Logia proviene del italiano loggia que eso significa en español galería y a la vez proviene del francisco ripuario laubja, que significa “cobertizo enramado”. Bueno ustedes se preguntarán ¿qué sentido tiene todo esto? toda esta etimología fue para explicar que el significado galería hace mención a las juntas, porque en el siglo XIII los albañiles empezaron a hacer juntas secretas contra los frailes, las juntas las hacían en lugares que no estaban los frailes como los cobertizos. La palabra masón es la que me llamo más la atención, ya que en albañil en inglés es masón ¿y que relevancia tiene eso? La creencia masónica se dividió en dos corrientes la regular (que es la tradición anglosajona) y la liberal (tradición francesa) eso demuestra que desde esos años (hablamos del siglo XIII) ya había conflicto entre ingleses y franceses. Lo que más admiro de todo esto es la gran cantidad de participantes que tiene independiente de que corriente tome, como una sencilla reunión de albañiles vaya tomando tal fuerza que llegue hasta otro país.

Continue reading Influencia de la Masonería en ChileIn Freemasonry the pomegranate is the emblem of the spiritual communion that binds the Brethren together during an initiation ceremony in the Lodge and (…)

In nature the pomegranate is native to the Middle East and Asia Minor and has been farmed there since ancient times.

However, it can thrive in a variety of soils and temperatures.

Pomegranates were thought to have aphrodisiac properties in antiquity and Hippocrates lauded its medicinal virtues.

To read the full article, click the link below:

Taverns, inns and coffee houses played a meaningful role in the expansion of Freemasonry (…)

The full article is now available for reading at the following link :

One of Prince Harry’s revelations in his book “Spare” is that his older brother, Prince William, disparagingly called his wife Meghan Markle a “difficult, unpleasant, and aggressive woman”.

Harry also says that his father, King Charles, is a person who does not tolerate anyone taking the spotlight off of him, as Diana undoubtedly did and Meghan was ostensibly about to do.

However, it is well known that the Duke and Duchess of Sussex attribute their present form of exile and loss of privileges to the prejudices within the Royal Family, their “aides” and the British media. Whether you believe her or not, the British royal family has a history of hiding royal descendants that don’t fit the norm.

The Windsors, who adopted this fanciful name to conceal their German extraction and legitimate name of Saxe Coburn Gotha, have always regarded Meghan Markel an undesired household member.

She is an American divorcee and former actress with an African heritage. Unlike Kate Middleton, Duchess of Cambridge, she does not have a noble lineage, no matter how feeble that may be. She is truly a common woman who, unfortunetly, also reminds the Royals of another difficult American divorcee : Wallis Simpson, for whom the unforgivable Edward VIII abdicated in 1936.

But look out because Meghan Merkel is most certainly neither the first nor the sole British Royal to have African ancestry; even Queen Charlotte was a mulatto!

The claim was made by an article printed in The Guardian in 2009 and written by Stuart Jeffries, from which I have extracted and edited the following piece.

WHO WAS CHARLOTTE MECKLENBURG-STRELIZ ?

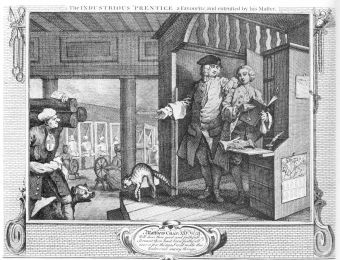

Continue reading The Black Queen of EnglandOne individual whose reputation lies far from that of the archetypal Huguenot is John Jean Misaubin (1673-1734). It has been estimated that there were some 470 Huguenot refugee who practised the profession of medicine in England, from the beginning of the Reformation until the Huguenots ceased to seek refuge under the reign of George III. Dr John Misaubin was a fashionable ‘quack’ known to posterity thanks largely to the famous image of him by William Hogarth (1697-1764). He has been identified since contemporary times as ‘the thinner of the two doctors in Plate V of ‘A Harlot’s Progress’ published in 1732‘.

Here they are arguing the merits of their respective pills and potions whilst their patient Moll Hackabout, the Harlot, is dying of venereal disease, the reward of their calling.

Unsurprisingly, in the light of Hogarth’s striking and damning portrayal of medical incompetence, veniality and lack of humanity, all succeeding commentators over the years have repeated a pejorative refrain and called Misaubin a “notorious quack”.

Misabubin has a presence in another of Hogarth’s great modern moral subjects’ series, his ‘Marriage a la mode’ of 1743-45.

The meaning of this scene, the third in the series, has always been particularly obscure. The impoverished Count with his young girl friend is visiting a quack who has been said to be Misaubin with his ‘Irish wife’. But not only the image is not a physical representation of Misaubin, his wife Martha (Marthe) Angibaud, was too a French Huguenot. Hogarth’s reference to Misaubin lies in the setting, thought by some commentators to represent Misaubin’s museum at 96, St Martin’s Lane. Here are shown two machines; one for pulling corks and the other for reducing dislocated shoulders! The open folio on the machines reads: ‘Explication de deux machines superbes l’un pour remettre l’épaules l’autre pour servir de tire bouchon inventés par Mons de la Pillule… — vues at approuvées par l’academie des Sciences a Paris’. The other specific reference to Misaubin is the dummy with the long wig in the cabinet indicated by the Count’s cane. Misaubin lived at this address only from 1732 until his death there in 1734.

Continue reading DR MISAUBIN – THE QUACK FREEMASONWhy behind the appearances ? Because we must ask ourselves whether the events of yesterday in Russia, were part of a perfectly performed play or a sequence of ruinous actions spoilt by unforseen circumstances. What we saw in the west yesterday was Putin‘s tense face on TV in the morning, denouncing the betrayal of Motherland and promising a severe punishment to those who had betrayed Motherland Russia. The media showed us the great flames of the sun with a films of the Wagner ‘s war vehicles roaring along the highway on their way to Moscow. And then surprisingly, as the day came to a close, the same media announced to us the granting by Putin of the impunity for the rioters, and a safe exile to Bielorussia of the Wagner’s vile leader.

JUNE 24TH – ST. JOHN’S MIRACLE

Why behind the appearances ? June 24th is the day the Christians celebrate this Saint around the world, but St John the Baptist is also the Saints’ Patron of Freemasonry ! And it was also on June 24, 1717, that the four main english Masonic lodges came together into one Grand Lodge giving birth to the “Modern” “speculative” Freemasonry. Two Protestant Christian excellent brothers, then wrote the new statutes of “Freemasonry” : the Reverend James Anderson and the Rev. John Theophilus Desaguliers.

MASONIC COINCIDENCES

In his book “Massoni”, WM Gioele Magaldi – Grand Master of the Grand Democratic Orient of Italy- basing himself on the thousands of documents that he boasts to possess – describes Vladimir Putin as a refined esotericist.

Worshipful Brother Magalli, wrote that Putin “has been a militant freemason for decades, together with Angela Merkel, both members of the “Golden Eurasia,” one of the many supranational Masonic structures which supervise the great decisions taken by the world governments.

The 1680s had been a difficult decade for London’s livery companies. The Crown’s attack on the ‘Whig’ faction and James II’s assault on the ‘Tories’ had caused them to surrender their charters and be purged of thousands of their members. Elizabeth I and James I had both extracted large sums from the companies. During the civil wars of 1640s and 1650s, it is impossible to know the exact amount they contributed to both the Crown and Parliament, mostly in loans that were never repaid. Against this backdrop of political attack, court action and financial stress, it is unsurprising that many members of the Masons’ Company were reluctant either to assume or to discharge the responsibilities of office. The Great Fire of 1666 destroyed 44 company halls and devastated their property portfolios, wiping out much of their rental income. The Masons’ Company was a going concern and by 1690 it went on its knees.

To pay for its royal charter, the Masons’s Company borrowed £800 from Anthony and Anne Light in return for 22 annual payments of £80. However, it was unable to meet its obligations and defaulted on the payments, increasing its debts. By the end of the 17th century, the Masons’s Company was so short of money that, in 1681, it agreed to have only a breakfast on Lord Mayor’s Day.

With the Rebuilding of London Act of 1667, the Parliament had unwisely removed for the building worker in London any economic or legal compulsion to join a Company or Guild, thus allowing any skilled labourer to work on the city’s reconstruction on the same terms as a freeman.

The Masons’ Company’s finances improved in the 1690s due to the return to political stability under William III and Mary II and through hard work, ingenuity and generosity, the Company’s finances were put back on a firmer footing.

In 1694, the Company applied for an Act to the London’s Common Council which required all those who worked as masons in London to join the Masons’ Company.

The Masons’ Company’s Act of 1696-1705 was an initial success, with 28 men admitted to the ranks between 1696 and 1705.

However, by 1706, the initiatives had run out of steam. To enlarge its membership, the Masons’ Company instituted two incentives: lowering its redemption fine from 36s to 3s 4d and offering a commission of 2s 6d for each admission. It seems that a lucrative market opened up at the Guildhall in redemption admissions because, following news that several other Companies were paying more for every member their ministers and officers brought , the Masons’ enhanced their gratuities to 6s.

This was an effective policy. In the 30-year period from 1676 to 1705 the Company had admitted 357 freemen but from 1706 to 1735 the number increased to 428.

More members meant more of their sons joining and receiving the freedom, which lead to more people paying quarterage and more people holding office.

David Gros or Le Gross, the Company’s clerk, was given one of the houses adjoining Masons’ Hall by the Court in January 1717 for his ‘good and faithful Services’ and efforts to introduce new members by redemption (i.e. by fee payment).

Le Gross was born in 1682 and was connected to the Gros or Le Gross of Cornwall. He was elected as clerk of the Masons’ Company in June 1708 and in 1717 he was serving as secretary to the governor and directors of the Bank of England. He probably ceased to work at the Guildhall, but he continued as clerk of the Masons’ Co, until February 1721. Le Gross was an important figure in early eighteenth-century London politics, finance and administration.

He was a prominent Whig and although not himself a Huguenot, he had connections with the French merchants and exchange brokers who established themselves in London’s stock exchanges and insurance markets. In 1708, Le Gross became Company clerk and introduced 21 admissions to the freedom of the Masons’ Company, five of which were exchange brokers. When the Masons’ Company court rewarded Le Gross for his efforts, they took particular note of the benefit and advantage the Corporation received from the many substantial Traders and others whom were recruited through his efforts. The Company’s intake of redemptioners in the early eighteenth century was cosmopolitan, with twelve of the 19 exchange brokers, admitted by redemption, not English. At least nine of those were Frenchmen wand identifiably Huguenot.

But the Company’s intake of international redemptioners was not limited to exchange brokers. Huguenots joined the Masons’ Company for the social and fraternal aspects of Company life, as it was a tradition in London, and to take the livery and thereby acquire the right to vote.

Two particularly noteworthy admissions by redemption were of women with French names, such as Mary Latour and Mary Paramor. Women had traditionally only participated in company life as wives or widows, but young women began to enter into corporate apprenticeships in greater numbers in the second half of the 17th century. As they completed those apprenticeships, they became eligible to join the Companies. In the first four decades of the 18th century, nine women – mostly business owners – took up the freedom of the Company by redemption. For example Anne Baker, who joined the Co. in March 1715, was a victualler in Finch Lane, while Anne Sparhawke and Katherine Wight, who were admitted to the freedom together in March 1735, were milliners and business partners.

Certainly, this study has shown that Huguenots diffused quite extensively into the wider livery as, indeed, they did into London society generally. It seems also that the new entrants were easily absorbed into the Masons’ Company’s ranks. There is no evidence for religious division in the contemporary Masons’ Company, and not once was the confession, or indeed the nationality, of those joining the Company marked next to the name of an entrant. A much liberal way than today! As far as members of the Masons’ Company were concerned, at least according to the official records, the Huguenots -and indeed Germans and Dutchmen -who joined the Company, were no different to any other freeman of London.

Children of Huguenot descent were admitted to the Company by patrimony, and Huguenots bound their children as apprentices. Between 1706 and 1735, two dozen of the 428 men and women who joined the Masons’ Company were identifiably as Huguenot, making them five per cent of the population of London.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, City’s companies completed their transformation into ‘corporations concerned primarily with the administration of their valuable freehold and trust estates and with sponsoring convivial, charitable and educational activities. In its early eighteenth-century history, no more than a dozen of the 32 men and women admitted to the freedom in 1712 identified as masons. In 1724, the Company admitted two attorneys at the Lord Mayor’s court and a clerk in the town clerk’s office, and in 1734, just 29 of the 70 men on the Company’s livery worked or had worked in the craft of masonry.

Throughout the 17th c. London Great Twelve companies had admitted more members unconnected with their traditional trades. As London’s workforce diversified and became increasingly specialised, the Masons’ Company’s membership began to disconnect from its traditional craft. This was a revolutionary development in the Company’s history and one with which Huguenots were clearly associated because none of those who joined the Masons’ Company were actually masons.

The Masons’ Company’s decision to lower its redemption fine and pay gratuities for referrals had long-lasting effects, helping to secure its future.

The Company experienced a remarkable turnaround in financial health by the end of the 17th century and certainly reached the nadir of its fortunes. In 1681, for example, it was so short of money that had agreed to have only a breakfast on Lord Mayor’s Day. In 1727, it was able to purchase £200 worth of interest-bearing stock and a property in Bishopsgate and in 1739, it spent well over £60 on food, drink, tobacco and music for the London Mayor’s Day. In 1680s and 90s the Co seems to have struggled to pay its pensions, yet in 1774, it was able to pay five men an annual pension of £2 each and seven widows one of £ 1 each. Membership of the Company was now much more attractive, worthwhile and fun.

Membership of the Company was, at the end of this remarkable period, much more attractive, worthwhile and fun and the change from operative into a speculative Freemasonry had thus just begun.

Extract from Ian Stone’s paper “Huguenots, Whigs and the Remodelling of the Masons’ Company, 1680-1740 – The Huguenbot Society Journal vol.35, 2022

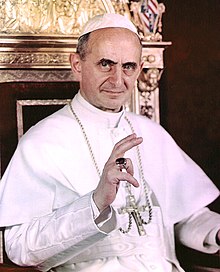

Religion, the Church and Freemasonry are not constantly at odds. Pope Pius IX [1], for example, was a Freemason born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti in the profane world. He was elevated to Pontiff on 16 June 1846 and had hardly been in that post three months when, to the huge regret of his masonic Brethren, he issued an encyclical against the Order. So much for Brotherly love!

Half a century later Angelo Roncalli and Giovanni Montini, better known respectively as Pope John XXIII (or the Good Pope) and Pope Paul VI, were also raised into the Great Mysteries of Freemasonry.

Both prelates saw themselves as enlightened heads of State and launched significant reforms of the Church, aimed at bringing it up with times. The changes introduced by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council are even based on the Masonic principles and postulates. The Council addressed the relationship between the Catholic Church and the contemporary world. The Council was formally opened under the pontificate of John XXIII on 11 October 1962 and was closed by Paul VI on 8 December 1965. The reforms, however, were regarded by many as heresies.

We do not know why Giovanni Pacelli/Pope Pius XII always denied the Cardinalate to Giovanni Montini. But on 24 November, 1958 Angelo Roncalli, twenty days after being installed on the throne of Peter as Pope John XXIII, wasted no time and made his brother of the Order a Cardinal at last, alongside twenty-three other prelates.

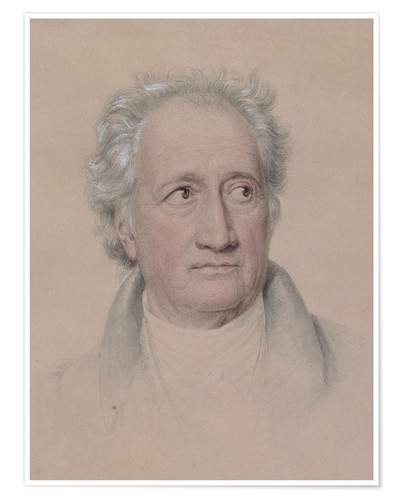

Continue reading FREEMASONS IN THE CHURCHAmong the most celebrated visitors to Italy of the 18th c. was the German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman and theatre director, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who dedicated a significant part of his work Italienische Reise (The Italian Trip) to his journey to Sicily, and left us a vivid impression of its inhabitants’ way of life.

Freemasonry officially appeared in Sicily, part of the Kingdom of Naples, in 1768 when England’s leading Grand Lodge in Naples conceded a warrant to the Perfect Union N. 433, which met in Palermo. The Lodge had been established by and for the benefit of military Irishmen under the command of Col. Francis Everard, but in order to survive it soon began to also admit civilians, culminating in Carlo Cottone, Prince of Villermosa, being its Worshipful Master at the end of 1785. There was another lodge in Palermo that operated under the rival National Grand Lodge of Naples, working on the rituals of the Rite Rectifié, successor of the Rite of Strict Observance, but it was in decline.

The Danish philosopher Friedrich Münter and Goethe were among the many Freemasons who in the 18th century visited the enchanting Mediterranean island. They were both disciples of Neo-Templarism and members of the Illuminati sect and had met in Rome. It is unquestionable that Goethe’s eagerness to broaden his Italian experience by visiting Sicily, rose directly from the description that Münter gave him of that captivating place. Goethe claimed he scheduled his trip to Palermo around the middle of March and that he delayed it on at least two occasions, only sailing from Naples on March 29th after he had learned that the vessel’s captain, Filippo Cianchi, was also a Freemason. Turbulence hampered the sea crossing, but Goethe safely arrived in Palermo on the bright afternoon of 2nd April. In Italienische Reise, he described the marvelous sensation he felt when he saw the gulf with on the right the Mount Pellegrino – “the most beautiful promontory in the world,” he called it – and the Conca d’oro on the left (The Golden Shell).

In Palermo, Goethe checked in at Mme. Montaigne’s hotel with the alias Philip Moeller. He hoped that by not revealing his true identity he would stay away from prying eyes, but to his surprise one evening, two men in uniform came to escort him to the Palace of the Viceroy, Francesco d’Aquino Prince of Caramanico. This nobleman had left the Dutch Lodge Les Zelés in Naples in 1769 to become a founding member and first Master of the Well Chosen Lodge, sanctioned by the Grand Lodge of England. He became also the Grand Master of the newly formed National Grand Lodge of Naples in 1773, but he resigned and withdrew from the Craft in 1775, when King Ferdinand IV banned Freemasonry in his realm.

It is unknown who had notified Prince Caramanico of the presence in Palermo, under an assumed identity, of the important German Brother; but it is reasonable to suspect the tip-off came from the Naples Freemasons. Other potential informers are the German landscape painter Jacob Philipp Hackert, who had met Goethe in Naples and had been Prince Caramanico’s guest at Palermo, the English Ambassador in Naples, Sir William Hamilton, and the ship’s Captain Cianchi himself.

Count Statella, the Viceroy’s Master of Ceremonies and a Knight of Malta, greeted Goethe on his arrival at the Palace. According to an anecdote, the Count – believing the visitor was a German called Philip Moeller – made an embarrassing blunder and casually mentioned that he had just finished reading “Werther,” a novel by another German named Goethe, whom he then talked about in derogatory terms. At this point Goethe revealed his true identity much to the dismay of the Count, who was even further embarrassed when the Viceroy, requesting him that Goethe be sat next to him at the table, grinned back at his Master of Ceremonies’ surprised reaction.

By traveling under a false identity, Goethe wanted to avoid contact with anyone from academic circles or high society and thus remain free to fully absorb and enjoy the island’s natural beauty. Despite his best efforts to remain incognito, however, we know he also met and frequented in Palermo the Baron Antonio Bivona, a lawyer engaged by King Louis XVI of France to investigate Giuseppe Balsamo and his family. Balsamo, a self claimed magician and healer who was using the alias Count Cagliostro on his far and wide travels in Europe, had become famous particularly for his frauds and supposed role in Queen Marie Antoinette’s necklace scandal. We know that in March 1787, the Baron had lent his report on Balsamo/Cagliostro to Goethe, who after reading it, visited Giuseppe’s mother and sister on Via Terra delle Mosche, a street in a much run-down area of Palermo.

This time Goethe introduced himself as an Englishman by the name of Mr. Winton, and informed the Balsamos that Giuseppe had traveled to London after being released from the Bastille. Goethe sympathized with the two destitute women, who had a big family to support and in Italienische Reise, he expressed the remorse for not being able to take care of them right away.

According to one account cited by several sources, on his return to Germany, Goethe showed his Brothers of the Order the letter that Giuseppe’s mother had written to her son, in which she begged for financial help. And those generous and caring men, moved by the tragic story, raised a sum of money and conveyed it to the Balsamo women via the English merchant Jacob Joff. The truth, however, may be that which is found in the memoirs of Brother Karl August Bottiger, a well-known archaeologist who knew Goethe and was a member of the Lodge Der goldene Apsel in Dresden. He wrote:

“(…) the amount delivered to the Balsamos was [just] the honorarium the publisher Unger had paid Goethe for his Der Gross-Cophta,” a satire on Freemasonry that was staged in 1791 and proved a failure.

Whatever version of the events you choose to believe, there is no doubt that the financial gift to the the Balsamos was a noble, generous gesture performed in classic Masonic fashion !

After traveling across the island of Sicily, Goethe came to the following conclusion about the locals , which is a strong testament of their bravery:

Messina, Sunday 13 May 1787 – “I thought how interesting it was to see how gentlemen could get together and speak freely and with impunity, under a dictatorial government, to protect their own as well as foreign interests.”

Extracted and revised by the Editor from the paper Goethe in Palermo written by Bro. M.R. Maggiore and published in AQC 1985,vol. 98, page 205-207