In the 18th century, actors were known as His Majesty’s Servants and were entitled to wear (…)

To read WBro Leonardo Monno’s full article, click on the link below:

In the 18th century, actors were known as His Majesty’s Servants and were entitled to wear (…)

To read WBro Leonardo Monno’s full article, click on the link below:

One individual whose reputation lies far from that of the archetypal Huguenot is John Jean Misaubin (1673-1734). It has been estimated that there were some 470 Huguenot refugee who practised the profession of medicine in England, from the beginning of the Reformation until the Huguenots ceased to seek refuge under the reign of George III. Dr John Misaubin was a fashionable ‘quack’ known to posterity thanks largely to the famous image of him by William Hogarth (1697-1764). He has been identified since contemporary times as ‘the thinner of the two doctors in Plate V of ‘A Harlot’s Progress’ published in 1732‘.

Here they are arguing the merits of their respective pills and potions whilst their patient Moll Hackabout, the Harlot, is dying of venereal disease, the reward of their calling.

Unsurprisingly, in the light of Hogarth’s striking and damning portrayal of medical incompetence, veniality and lack of humanity, all succeeding commentators over the years have repeated a pejorative refrain and called Misaubin a “notorious quack”.

Misabubin has a presence in another of Hogarth’s great modern moral subjects’ series, his ‘Marriage a la mode’ of 1743-45.

The meaning of this scene, the third in the series, has always been particularly obscure. The impoverished Count with his young girl friend is visiting a quack who has been said to be Misaubin with his ‘Irish wife’. But not only the image is not a physical representation of Misaubin, his wife Martha (Marthe) Angibaud, was too a French Huguenot. Hogarth’s reference to Misaubin lies in the setting, thought by some commentators to represent Misaubin’s museum at 96, St Martin’s Lane. Here are shown two machines; one for pulling corks and the other for reducing dislocated shoulders! The open folio on the machines reads: ‘Explication de deux machines superbes l’un pour remettre l’épaules l’autre pour servir de tire bouchon inventés par Mons de la Pillule… — vues at approuvées par l’academie des Sciences a Paris’. The other specific reference to Misaubin is the dummy with the long wig in the cabinet indicated by the Count’s cane. Misaubin lived at this address only from 1732 until his death there in 1734.

Continue reading DR MISAUBIN – THE QUACK FREEMASONComte de Cagliostro, an enigmatic figure of the Age of Enlightenment, whose identity and motives are still up for deliberation, inspired both Alexander Dumas to write the novel The Memoirs of a Physician and Goethe’s five-act play Deer Gros-Cophta.

The world is divided over whether he was an adventurer, a compassionate individual who used his profound knowledge of alternative medicine to help the sick, a teacher of the occult, or a charlatan who preyed on gullible rich people. Some identify the Comte de Cagliostro with the Jesuit raised fraudster Giuseppe Balsamo from Palermo, Sicily; others think he was the Comte de Saint-Germain, an alchemist who had discovered the secret for ubiquosity–being in more places at the same time – and eternal life.

Whatever you may believe, there is little doubt, however, that Cagliostro’s power to seduce has lasted the test of time. He said: “The truth about me will never be written because nobody knows it”.

As for whence he came, he declared: “I am not of any time or any place; beyond time and space my spiritual being lives an eternal existence (…) my country is wherever my feet stand at that moment.”

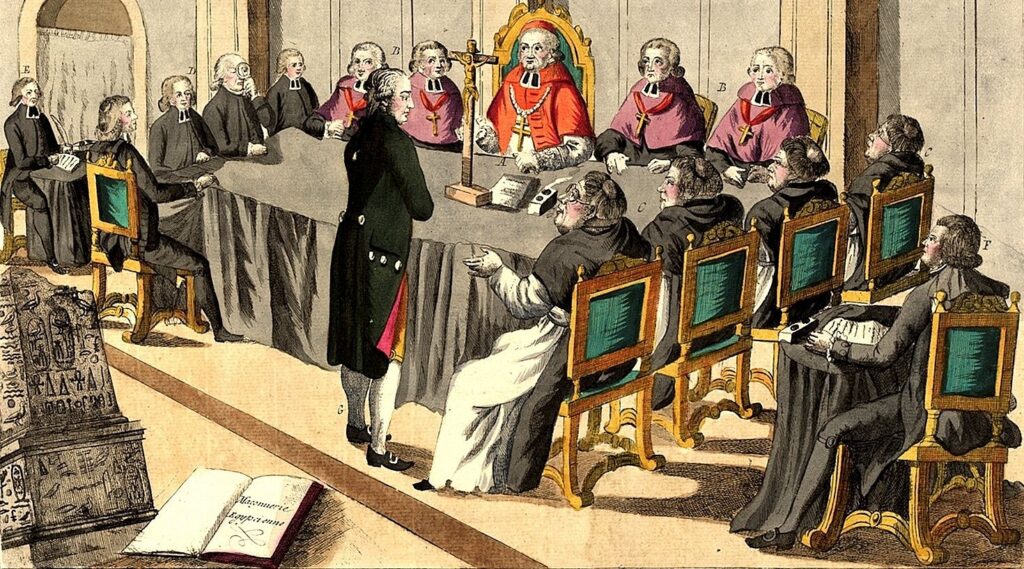

On December 27, 1789, the self-styled Comte de Cagliostro was arrested in Rome and taken to Castel Sant’Angelo, where he was held until his trial before the Holy Inquisition Tribunal. He received the death penalty, which was later commuted to life imprisonment at the Forte San Leo, where he passed away on August 26, 2006, six years later. However, neither his grave nor body has ever been found.

The self-styled Count was the founder of a new Masonic Order he called Egyptian under whose roof he attempted to bring both the Masonic movement and Christianity.

He founded the Mother Lodge of Egyptian Masonry in Lyons in 1784/86.

Cagliostro, the Grand Priest (Copt) of the Order, promised that he could lead his disciples to perfection and heal their bodies and souls. The philosopher’s stone would give his adepts immortality, the sacred talisman of the Pentagon promised them the obtain that innocence of spirit and perfection that belonged to Adam, the primal man.

THE TWO PROPHETS

According to legend, Comte de Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite was inspired by the belief of immortality held by the prophets Enoch and Elias. Enoch, the seventh descendant of Adam (Jude 1:14), is said to have been “translated (by God) (so) that he should not experience death and he was never been found” (Heb. 11:5).

The term translated implies that Enoch was taken somewhere other than Heaven, which is a place where God dwells and where only a soul of the highest purity, such as Jesus Christ’s, can be allowed access.

Continue reading CAGLIOSTRO’S EGYPTIAN RITELondon was the 18th century wonder capital of Europe. It had been rebuilt following the Great Fire of 1666 and had an extremely new look. The merchants had withdrawn from the City and moved into fashionable terrace houses in the parishes of Soho, Mayfair, and in St. James, which had broad streets and paved squares.

And yet, London continued to be surrounded by miasma and be a city broadly tarnished by horse-dung. In the absence of an adequate sewerage structure, many servants still discharged their master’s chamber pot upon the heads of passersby and because of the coal burning in the fireplaces, layers upon layers of black soot coated the buildings and made the air not healthy to inhale. Violence and street crime were rampant.

THE WORLD OF THE OPERA IN LONDON

It was in this almost surreal habitat that deep connections were established between Freemasonry and the world of music, and they have never been stronger than during those years.

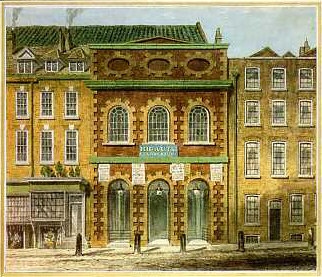

With the upper social classes having so much available time in hand and a strong love for entertainment, London turned into a Mecca for foreign artists. Since 1708, the Italian Opera had been constantly performing, with varying fortunes, at the Queen’s Theater in Haymarket, London, which is now called Her Majesty’s Theater. Built in 1705 and renamed the King’s Theater in 1714 upon the ascension to the throne of Great Britain of the German born George I (1626-1727), the theater also became identified for a period as The Italian Opera House.

The ceaseless comings and goings of French, German and Italian musicians, singers and impresarios continued strongly into the following century and the King’s Theater audience was never entertained with as many comic operas as it was in the season 1768-69.

The international artists all detested the English climate, which brought them colds and fevers, but they never regarded this poor factor as a reason for not coming back if awarded a contract. Aliens had also learned to put up stoically with the infamously atrocious English food and an Italian representative of the 1763 King’s Theater recounted his experience of it in these terms:

“In this expensive metropolis, we poor Christians are reduced during Lent to the melancholy alternative of either fasting like our founder, or living on rotten eggs, stinking fish, train-oil, and frost-bitten roots and herbage’’.

HOSTILITY TOWARDS FOREIGNERS

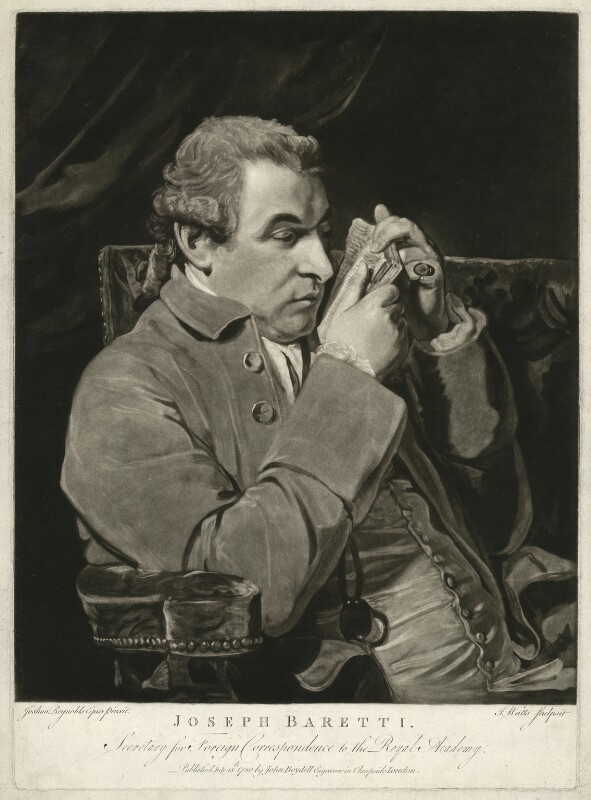

The Italian literatus Giuseppe Baretti (1719-1789), compiler of the first English-to-Italian vocabulary, devoted most of his life in London and denounced the poverty that existed among Italian singers in London, which was created by inadequate earnings and exceedingly costly existence. He did so in a letter printed in The Public Ledger of 16 September 1760, which received this response:

“We can now see into the penury and meanness of those who have gained thousands by our folly and extravagance – we know, while in England. how miserably they live, because they will save all they can to spend in their own country; (…) such is their hatred of the nation that caresses them, that if it were possible to live upon the dirt or filth of the streets, they would rather do it than the least farthing should come back again into an Englishman’s pocket“.

The London society, had always harbored animosity towards aliens–the 1666 Great Fire of London was attributed on a French catholic, after all – and accused the Italians of avarice for their meager spending, neglecting that the aristocrats kept artists waiting around without work or payment for days or even weeks at a time. They did not understand the struggles the touring musicians suffered and would not have cared less even if they did.

Samuel Johnson declared that in London one discovered the “full tide of human existence,” and that although the Capital of England was “a place with a diversity of greed and evil (…) slight vexations do not fix upon the heart” of its residents. In my opinion, he never asked them.

THE NINE MUSES LODGE

Networking was an important chore for all the foreigners who visited England, whether they were artists, merchants, aristocrats, or rich gentlemen. At best, it assured admittance into affluent and patrician circles, at worst it guaranteed contracts and even a profitable office.

And what better way to network than by joining a Masonic Lodge?

On January 14, 1777, these individuals convened in the Thatched House Tavern on St. James’s Street, Westminster–which at the time was regarded as being part of the County of Middlesex – and on the 23rd, after securing a warrant, formed the Lodge of the Nine Muses No. 502.

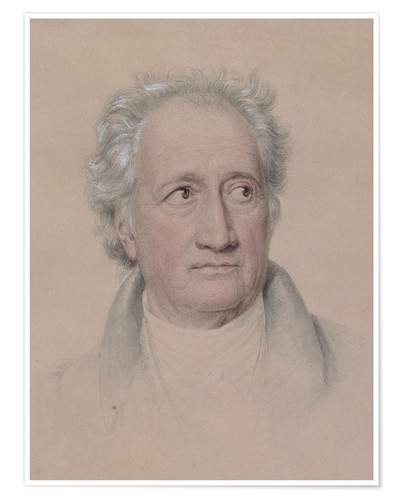

Continue reading MUSIC AND THE CRAFT – LUIGI BORGHI , A FREEMASON OF THE NINE MUSES LODGEAmong the most celebrated visitors to Italy of the 18th c. was the German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman and theatre director, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who dedicated a significant part of his work Italienische Reise (The Italian Trip) to his journey to Sicily, and left us a vivid impression of its inhabitants’ way of life.

Freemasonry officially appeared in Sicily, part of the Kingdom of Naples, in 1768 when England’s leading Grand Lodge in Naples conceded a warrant to the Perfect Union N. 433, which met in Palermo. The Lodge had been established by and for the benefit of military Irishmen under the command of Col. Francis Everard, but in order to survive it soon began to also admit civilians, culminating in Carlo Cottone, Prince of Villermosa, being its Worshipful Master at the end of 1785. There was another lodge in Palermo that operated under the rival National Grand Lodge of Naples, working on the rituals of the Rite Rectifié, successor of the Rite of Strict Observance, but it was in decline.

The Danish philosopher Friedrich Münter and Goethe were among the many Freemasons who in the 18th century visited the enchanting Mediterranean island. They were both disciples of Neo-Templarism and members of the Illuminati sect and had met in Rome. It is unquestionable that Goethe’s eagerness to broaden his Italian experience by visiting Sicily, rose directly from the description that Münter gave him of that captivating place. Goethe claimed he scheduled his trip to Palermo around the middle of March and that he delayed it on at least two occasions, only sailing from Naples on March 29th after he had learned that the vessel’s captain, Filippo Cianchi, was also a Freemason. Turbulence hampered the sea crossing, but Goethe safely arrived in Palermo on the bright afternoon of 2nd April. In Italienische Reise, he described the marvelous sensation he felt when he saw the gulf with on the right the Mount Pellegrino – “the most beautiful promontory in the world,” he called it – and the Conca d’oro on the left (The Golden Shell).

In Palermo, Goethe checked in at Mme. Montaigne’s hotel with the alias Philip Moeller. He hoped that by not revealing his true identity he would stay away from prying eyes, but to his surprise one evening, two men in uniform came to escort him to the Palace of the Viceroy, Francesco d’Aquino Prince of Caramanico. This nobleman had left the Dutch Lodge Les Zelés in Naples in 1769 to become a founding member and first Master of the Well Chosen Lodge, sanctioned by the Grand Lodge of England. He became also the Grand Master of the newly formed National Grand Lodge of Naples in 1773, but he resigned and withdrew from the Craft in 1775, when King Ferdinand IV banned Freemasonry in his realm.

It is unknown who had notified Prince Caramanico of the presence in Palermo, under an assumed identity, of the important German Brother; but it is reasonable to suspect the tip-off came from the Naples Freemasons. Other potential informers are the German landscape painter Jacob Philipp Hackert, who had met Goethe in Naples and had been Prince Caramanico’s guest at Palermo, the English Ambassador in Naples, Sir William Hamilton, and the ship’s Captain Cianchi himself.

Count Statella, the Viceroy’s Master of Ceremonies and a Knight of Malta, greeted Goethe on his arrival at the Palace. According to an anecdote, the Count – believing the visitor was a German called Philip Moeller – made an embarrassing blunder and casually mentioned that he had just finished reading “Werther,” a novel by another German named Goethe, whom he then talked about in derogatory terms. At this point Goethe revealed his true identity much to the dismay of the Count, who was even further embarrassed when the Viceroy, requesting him that Goethe be sat next to him at the table, grinned back at his Master of Ceremonies’ surprised reaction.

By traveling under a false identity, Goethe wanted to avoid contact with anyone from academic circles or high society and thus remain free to fully absorb and enjoy the island’s natural beauty. Despite his best efforts to remain incognito, however, we know he also met and frequented in Palermo the Baron Antonio Bivona, a lawyer engaged by King Louis XVI of France to investigate Giuseppe Balsamo and his family. Balsamo, a self claimed magician and healer who was using the alias Count Cagliostro on his far and wide travels in Europe, had become famous particularly for his frauds and supposed role in Queen Marie Antoinette’s necklace scandal. We know that in March 1787, the Baron had lent his report on Balsamo/Cagliostro to Goethe, who after reading it, visited Giuseppe’s mother and sister on Via Terra delle Mosche, a street in a much run-down area of Palermo.

This time Goethe introduced himself as an Englishman by the name of Mr. Winton, and informed the Balsamos that Giuseppe had traveled to London after being released from the Bastille. Goethe sympathized with the two destitute women, who had a big family to support and in Italienische Reise, he expressed the remorse for not being able to take care of them right away.

According to one account cited by several sources, on his return to Germany, Goethe showed his Brothers of the Order the letter that Giuseppe’s mother had written to her son, in which she begged for financial help. And those generous and caring men, moved by the tragic story, raised a sum of money and conveyed it to the Balsamo women via the English merchant Jacob Joff. The truth, however, may be that which is found in the memoirs of Brother Karl August Bottiger, a well-known archaeologist who knew Goethe and was a member of the Lodge Der goldene Apsel in Dresden. He wrote:

“(…) the amount delivered to the Balsamos was [just] the honorarium the publisher Unger had paid Goethe for his Der Gross-Cophta,” a satire on Freemasonry that was staged in 1791 and proved a failure.

Whatever version of the events you choose to believe, there is no doubt that the financial gift to the the Balsamos was a noble, generous gesture performed in classic Masonic fashion !

After traveling across the island of Sicily, Goethe came to the following conclusion about the locals , which is a strong testament of their bravery:

Messina, Sunday 13 May 1787 – “I thought how interesting it was to see how gentlemen could get together and speak freely and with impunity, under a dictatorial government, to protect their own as well as foreign interests.”

Extracted and revised by the Editor from the paper Goethe in Palermo written by Bro. M.R. Maggiore and published in AQC 1985,vol. 98, page 205-207

Sir Bernard Henry Spilsbury was the most distinguished medical detective in England and a Freemason, like some of his colleagues and the criminals he helped bring to jail. Only the imaginary character of Sherlock Holmes exceeds him in popularity.

Spilsbury was responsible, with Scotland Yard, for the introduction of the “Murder Bag” following the “Crumbles murder” case in 1924. Patrick Mahon had killed Emily Kaye, his lover, and then dismembered her body and when Spilsbury arrived on the murder scene, he was surprised to find investigators picking up body parts with their bare hands. As a result, he devised a kit consisting of a collection of instruments – tweezers, evidence bags, and other items -which forensic detectives presently still use.

Spilsbury was also responsible for establishing the character of the “legal expert” by integrating pathology and cause-of-death examinations into the legal criminal context.

— *** —

Bernard Henry Spilsbury was born on January 16, 1877, in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, England and was one of four offspring from the union between Marion Elizabeth Joy and James Spilsbury, a chemist. Bernard adopted his father’s passion for science but – according to the crime author Michael J Buchanan-Dunne – he also absorbed his coldness, arrogance and lack of empathy. After receiving home education, at the age of nine Bernard was sent to boarding school for three years and at the age of 15, with his parents living in Crouch End in London, he went to study chemistry, physics and biology at the Owen’s College in Manchester.

In 1895 Bernard Spilsbury enrolled at the Magdalen College, Oxford and earned his BA in natural science in 1899. He subsequently attended St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School in Paddington’s Praed Street, London, where he meant to qualify as a general practitioner. Instead, he went on to study pathology and never repented.

Continue reading SPILSBURY – THE FREEMASON FATHER OF FORENSIC SCIENCEJulia Apraxin was initiated into a Masonic lodge called “Fraternidad Iberica” (Brotherhood of Iberia) in Madrid in 1880. Although born in Vienna, she felt also Hungarian, owing to her upbringing in that country and the possibility that his Hungarian foster father was, in fact, her biological parent. “Doña Julia de Rubio y Guillén, Condesa de Apratxin” was admitted into the lodge Fraternidad Ibérica (Brotherhood of Iberia) of the Grande Oriente Nacional de España (National Grand Orient of Spain) in Madrid on June 14, 1880, in accordance with contemporary Spanish Masonic protocol. The letter “t” in the countess’ surname appears to have been a slip of the pen.

Seoane, the Grand Master of the National Grand Orient of Spain, gave his authorization to initiate her by citing the lady’s gallant services for the French army as official chronicles evince. The lodge minutes show a considerable participation of Freemasons to the function and that Countess “Apratxin” adopted for herself the name “Buda.”[1] Julia Buda was merely one of the many aliases that the Countess used in her life; she had been inspired to it by the name of the former Capital city of Hungary, Buda[2], one of her places of residence and activities.

Julia’s mother had met Count József Esterházy in 1828, and after her first husband had divorced her, the two wed in 1841. Count Esterházy – we know from his diary – regarded Julia to be his own daughter.

Julia Apraxin was born on October 16, 1830, in Vienna, the registered offspring of Count Alexandre Petrovich Apraxin, a Russian noble and diplomat, and Countess Hélène (Ielena) Bezobrazova, a Polish-Russian aristocratic. Julia spent her childhood and adolescence in Vienna and at the Esterhazy Castle in Cseklész, near Pozsony (today Pressburg, Bratislava), with her parents and brother Demeter .

On October 15, 1849, she married Count Arthur (Artúr) Batthyány. The couple had five children and for about ten years settled in Vienna, where they lived the glamorous life of high society, attending balls, dances, masquerades, and enjoying drives in their private carriage.

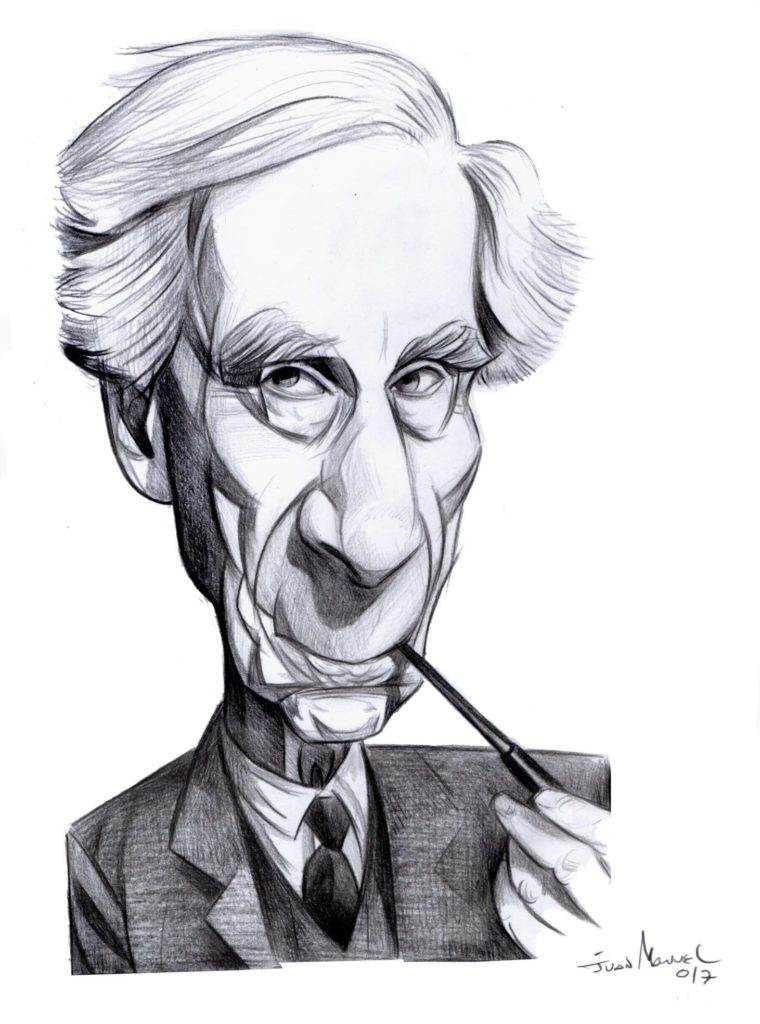

Continue reading JULIA APRAXIN – THE FIRST WOMAN FREEMASON IN SPAINThe British philosopher, essayist, social critic and Freemason Bertrand Russell, who is best known for his work in mathematical logic and analytic philosophy wrote in “the Scientific Outlook” in 1931:

On those rare occasions, when a boy or girl who has passed the age at which it is usual to determine social status shows such marked ability as to seem the intellectual equal of the rulers, a difficult situation will arise, requiring serious consideration. If the youth is content to abandon his previous associates and to throw [himself] whole-heartedly with the rulers, he may, after suitable tests, be promoted. But if he shows any regrettable solidarity with his previous associates, the rulers will reluctantly conclude that there is nothing to be done with him except to send him to the lethal chamber before his ill-disciplined intelligence has had time to spread revolt.

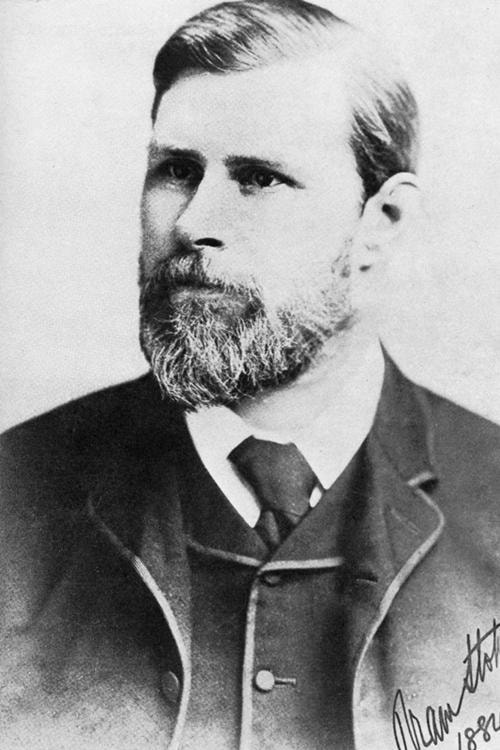

George Weifert – Djordje Vaifert (1850-1937) – is arguably the most distinguished promoter of Serbian Freemasonry. His Masonic career, spanning some forty-seven years (1890-1937), is the story of the beginnings of Serbian and Yugoslavian Freemasonry, of its growth and of the turbulent times in which it existed.

Weifert was the first Master of one of the original Lodges in Serbia[1], Sovereign Grand Commander of the Supreme Council of Serbia[2], Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians-Yugoslavia (Velika Loza Srba, Hrvata/Slovenaca-Jugoslavija)[3], from its founding in 1919 till 1933, and a Sovereign Grand Commander of the Supreme Council of Yugoslavia Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite from 1919 till 1937[4].

During Weifert’s time, the Balkan Peninsula was a hotbed of religious, ethnic, and political conflict, as indeed it still is today, and in which everybody seemed to be involved. Many members of the Craft held eminent positions in political, economical and cultural life. Many of them often failed to distinguish between their professional obligations, patriotic duty and Masonic activity. This made Freemasonry in Serbia an easy target for anti-Masonic propaganda. George Weifert recognized this problem early on. As a leader in Serbian Freemasonry, he always insisted on keeping religion and politics separate from the Craft and out of the lodge, despite the fact that this was to prove an almost impossible task.

Let us but examine Weifert’s history and we will see that he was a true builder, a man of vision, an example of a freemason who lived what he taught, and a true ‘pillar’ of Freemasonry.

HIS EARLY YEARS

Weifert was born in Pancevo on 15 June 1850. His father and mother – Ignjat and Ana Weifert – were both German, Catholic and citizens of Hungary, which was at that time a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire[5]. Pancevo was a small Hungarian border town on the banks of the river Danube, populated with a mix of German, Hungarian and Serbian merchants and artisans. On the opposite bank of the Danube stood Belgrade the commercial centre and capital of the newly emerging kingdom of Serbia, at that time still formally a part of the dying Ottoman Empire[6].

Weifert’s grandfather moved to Pancevo in the beginning of the 19th century, trying his luck first as a wheat merchant and then as a brewer of beer. In order to improve his business he sent his son Ignjat to Munich, where he spent time working and studying beer production in the famous Spatenbrau Brewery. Upon his return home, Ignjat Weifert and his father built the largest brewery in Pancevo, still in existence today[7]. In 1865 they rented an existing brewery [8] in Belgrade, and started production there in order to avoid the cost of transporting the beer from Pancevo to Belgrade.

Young Weifert attended the German Elementary School and the Hungarian High School in Pancevo, after which his father sent him to Budapest, where in 1869 he graduated from the Merchants Academy. In accordance with the family business needs, he then attended the Agricultural School in Weihenstofen, near Munich, where he concentrated his studies on beer production technology. After graduation in 1872 he returned to Belgrade, in order to help with his father’s rapidly growing business.

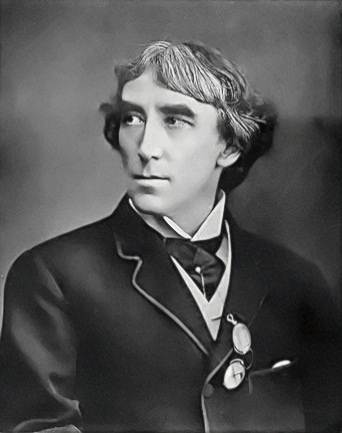

Continue reading WEIFERT GEORGE – A PILLAR OF SERBIAN FREEMASONRYThe second half of the 19th and early part of the 20th century was a period characterized by the coming into this world of many brilliant individuals who shone in the liberal arts. Bram Stoker was a writer and a Freemason who earned his stand by leaving us the immortal legacy of the successful gothic novel Count Dracula.

Stoker was born in Dublin in 1847 and attended Trinity College, where he received a bachelor’s degree in science in 1870 and a Master in mathematics later. He confessed that until he was seven years of age he could not properly stand up and yet he recovered and turned into a strong, hearty, athletic man, with an immense appetite for work and a remarkable appearance.

Stoker begun his career in the Irish civil service , working as a clerk in the Registrar Office of Petty Sessions in Dublin Castle. But his passionate interest in the dramatic art lead him to do unpaid work as a theatre critic for the Dublin Evening Mail.

In Dec 1876, following a performance of the Hamlet that he attended and brilliantly reviewed, Stoker was invited to meet the lead actor. The event marked the beginning of a 28 years association of Stoker with the most dominant, in every sense of the word, personality of his life, the legendary English actor John Henry Broadribb , better known with the stage name of Henry Irving.

When in 1879 Irving invited Stoker to manage both his performing career and the running of the Lyceum Theatre in Covent Garden, London, Stoker dropped everything in Dublin and run to assist – literally and in everything – the man he worshipped and who in turn exploited the situation to his advantage.

One obituary reads:

Continue reading THE FREEMASON WHO WROTE DRACULA – BRAM STOKER